In the Historic Northeast, east of downtown and just beyond Interstate 29, lies Belvidere Park — what now may appear to be an empty space. But at the turn of the 20th century, the area was a burgeoning Black neighborhood. A local reader reached out to What’s Your KCQ? — a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star — to see if Belvidere Hollow still exists. The short answer is no, but that comes with a story.

Local History Blog

A reader was intrigued by a handful of concrete structures resembling skateboard ramps on a grassy area off The Paseo, near 58th Street and Lydia Avenue — and reached out to What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between The Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, for an explanation. From a distance, these curved concrete surfaces bear a resemblance to ramps at a skatepark. But a closer look reveals gentle slopes interspersed with grassy patches, which would make skateboarding impractical. Instead, this is the site of the 49/63 Neighborhood Fountain, owned and maintained by Kansas City Parks and Recreation. Unfortunately, the fountain is not currently operational.

Today, Guinotte Avenue is a rather unassuming stretch of road running through Kansas City’s predominantly industrial East Bottoms. One hundred seventy years ago, however, the thoroughfare was the embodiment of one man’s dream to make Kansas City a global city and a center of Belgian immigrant culture in North America. Its history intrigued a local reader who asked What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, for insight. Joseph Guinotte, the namesake of Guinotte Avenue, was born in the French-speaking Belgian city of Liège in 1815. A well-respected engineer by the early 1840s, he was appointed by Belgium’s king, Leopold I, to oversee construction of a railroad from Mexico City to Veracruz — under a government agreement to send engineers to construct railways in Mexico with Belgian materials. Before departing, Guinotte proposed to his sweetheart, Aimée Brichaut, and left with her promise that she would join him once he had settled in North America.

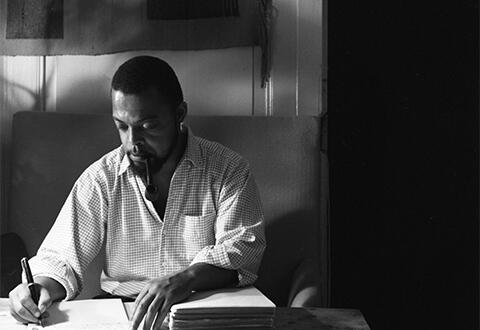

In June 2023, I travelled to Kansas City to research the early life of Vincent O. Carter, an African American writer who was born there in the North End in 1924. He was drafted into the Army at age 19 and sent to France. His unit arrived in Normandy shortly after the D-Day invasion at a time when all American troops, regardless of skin colour, were greeted as heroes. When Carter returned to the U.S., the G.I. bill enabled him to study English at Lincoln University. After graduating in 1950, he worked in an automobile plant in Detroit and saved money to return to Europe.

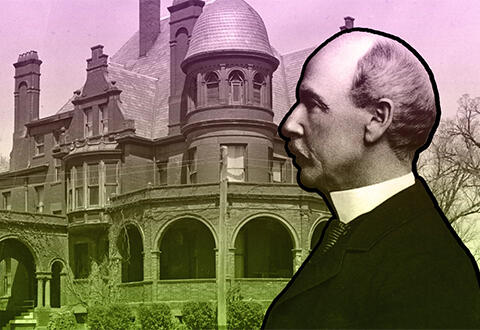

For more than a century, Kansas City has been haunted by the mysterious death of philanthropist Thomas Swope. Suspect number one is his nephew-in-law, Dr. Bennett Hyde, who stood to inherit a sizable portion of the Swope family fortune. But did Hyde really murder Thomas Swope, or was the physician actually the victim of a longstanding family grudge? This question was at the center of one of the most publicized murder trials of the early 20th century. Producer Mackenzie Martin walks host Suzanne Hogan through the evidence of this still-unsolved mystery.

Walking past Dr. Jeremiah Cameron Park in Westport, a reader noticed a marker for something called the Penn School and wrote to What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to learn about it. The park, located on Broadway Boulevard between 42nd and 43rd streets, marks the “Penn School Historic Site,” and was named for an alumnus of the Penn School who was an educator and the second Black member of the Missouri Parks and Recreation Board. The class of 1933 dedicated the plaque in homage to their alma mater in 1992. As of this writing, the plaque is missing — a reminder of the shaky role markers play in preserving local history and the challenges of making that history known.

While the hot dog is considered quintessential cuisine for the July Fourth holiday, the hamburger is undeniably king among American eats. It is a menu staple at restaurants throughout the U.S., not to mention the backyards and ballparks in which countless grilled patties are served up and consumed. Kansas City has its own juicy burger history — the focus of this installment of What’s Your KCQ?, an ongoing series produced by the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star. A reader recently perused the Library’s 1940 Tax Assessment Photograph Collection, a photographic survey of Kansas City buildings and residences, and noticed numerous hamburger stands around the downtown area. Town Topic and White Castle were two familiar names, but Bungalow, Eat-Moore, Happy Hollow, and many others were not.

Many assume Lee’s Summit was named for Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and a reader asked What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library, to find out the truth. Not only is the Kansas City, Missouri, suburb not named after Robert E. Lee, but the town didn’t take its name from anyone named Lee at all. Rather, it’s named after an early resident, a physician named Dr. Pleasant John Graves Lea. Born in the first decade of the 19th century in Tennessee, Pleasant Lea came to Jackson County around 1850. He settled in the area then known as Big Cedar with his wife Lucinda, their nine children, and his brother. The Leas became respected members of the community; each served a stint as postmaster in the 1850s, and Dr. Lea acted as the town physician as well.

With Mother’s Day weekend approaching, it is fitting that What’s Your KCQ? respond to a query about Kansas City’s Pioneer Mother sculpture in Penn Valley Park.

“Grandma has come out of the kitchen.” The North Ameri-Kansan, a weekly magazine from North American Aviation’s Kansas City, Kansas, plant, proudly proclaimed this in November 1942. It wasn’t just one, either. Thirty-nine women with grandchildren were known to by employed by North American Aviation at that time. “My family was grown and I was free to go to work,” declared Vinita Stephens. With two sons in the armed forces, she decided to support their efforts by working on the assembly line. Women of all ages were entering the work force throughout the U.S. in the early 1940s as the Allied war effort ramped up. Many of them were right here in Kansas City. Some were in occupations historically thought of as women’s work, such as secretarial jobs and sewing. Others worked on assembly lines building airplanes at Pratt and Whitney and North American Aviation, or with bullets and artillery shells at the Lake City and Sunflower Ordnance plants.