On September 8, 1965, the Kansas City Times started its 98th year of publication. The biggest story that morning was how Hurricane Betsy was pounding Florida. The storm was over 600 miles across, had hit Miami Beach with 81 m.p.h. winds, and crashed 20 foot waves near Fort Lauderdale, wreaking damage to roads, homes, and businesses.

In other stories, Gov. Hearnes was thinking about turning reapportionment over to the courts; Superintendent James Hazlett asked for a list of civil rights leaders to serve on a committee advising on school integration issues; Johnson County announced a referendum on fluoridation for December 5th; Mrs. J.B. Gailott of New Orleans, who believed in the religious right to segregation, reluctantly told her 19-year-old son to take his draft physical; the New York Yankees announced that manager Johnny Keane, whose St. Louis Cardinals of the year before had defeated the Yankees in the World Series, had been re-signed for the 1966 season, even though his 1965 Yankees hadn’t fared too well; and Robert Lloyd, an American Nazi, tried to enlist in the WAVES, the women’s part of the U.S. Navy.

At the movie houses, audiences could see My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, Goldfinger, The Hallelujah Trail, and the Beatles’ second movie, Help.

It was also the first day of school for Kansas City students.

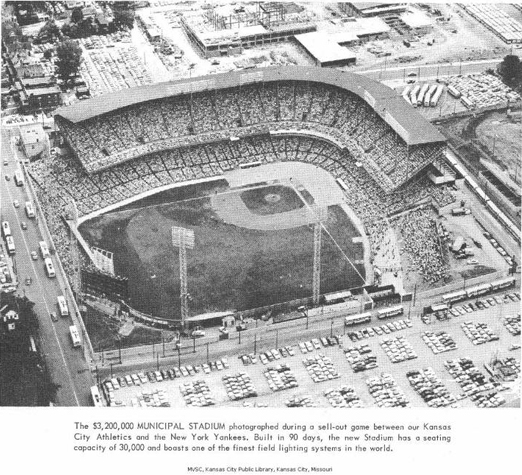

That evening, nine-year-old Mark Johnson’s parents, Stan and Norma, took him to Municipal Stadium to watch the Kansas City A’s host the Los Angeles Angels. (Earlier that week, the Angels had officially changed their name to the California Angels, but old habits die hard.)

The next morning, the Johnson family’s picture showed up on page 3 of the Times. The photographer had caught their reaction to Bert Campaneris stealing of his 49th base of the season.

Dagoberto Campaneris was the Athletics’ rising star, and had been brought up from the Birmingham team the previous year. On July 23, 1964, he had arrived in Minnesota just a couple of hours before the game’s start, after flying all night to get there. He was the leadoff hitter, and on his first at-bat in the majors he walloped Jim Kaat’s first pitch for a home run. He hit a second home run in the 7th, and made his first major league steal.

The A’s won in extra innings.

That didn’t happen nearly as often as Charlie Finley, the A’s owner, would have wanted. It hadn’t happened that often for Arnold Johnson, Finley’s predecessor as owner, either — of course, Johnson had the habit of selling the contract of any promising player on his team to the Yankees.

Charlie O. Finley

Cuban-born Campaneris was a multi-talented player, and played shortstop for the A’s. The fans loved him. By the time the ’65 season ended, his .270 batting average was Kansas City’s best, and his 12 triples and 51 stolen bases led the American League.

Finley decided to take advantage of all that talent and good will.

Consistent losing in major league baseball tends to lead to inconsistent attendance. One of the most consistent things about the Kansas City A’s was losing games. They had talented players, and it didn’t take too long after Finley moved the team to Oakland for that talent to mature into one of the strongest dynasties of the 1970s, but in 1965 the A’s winning a World Series was nothing more than a dream.

Charlie Finley was a pretty good promoter — maybe not first-tier, because Bill Veeck more or less had staked that out all to himself — but Finley was solidly in the second tier. Once, in a move that (as a grad of Central Missouri State) delights me, Finley smuggled a mule past the Chicago White Sox. And shortly after the events of September 8, he signed Satchel Paige to pitch for the A’s. Paige was 59, and Finley provided him with a rocking chair.

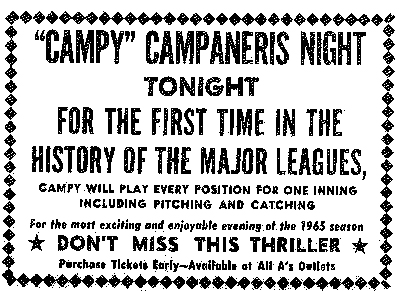

Having a talented and admired player like Campaneris, and low attendance, Finley decided to play one off the other, and announced a “CAMPY” CAMPANERIS NIGHT, in which Campaneris would rotate each inning and play all nine positions in one game.

It was pretty successful. The Johnson family showed up, along with 21,573 other fans.

The only position at which Campaneris had no real experience was first base. He had played catcher when he started in Cuba, where he had also pitched. Since turning pro he had played across the outfield, as well as played second, third, and shortstop.

Finley announced that the team had insured the A’s star through four insurance companies for a million dollars — or for a one and a half million, depending on whether you read the Times or the Star. Finley said that Campaneris was “too valuable a player” not to take the precaution. He also compared the situation to movie companies insuring the legs of famous actresses like Marlene Dietrich and Ginger Rogers.

Campaneris started the game at shortstop, his regular position. He got a walk as the leadoff batter, and stole that 49th base for the season, which led to his scoring a run. In the second inning he got an assist in a rundown while playing second. He had little to do in the third while playing third, and caught a fly each in both the fourth and fifth innings while in left and center fields. In the sixth inning, with two outs, he dropped a fly in right field, and a runner scored from first base, putting the Angels out front 2-1.

In the seventh inning Campaneris moved to first base, where he got an out, catching an infield fly.

In the eighth he went to the mound to pitch, where he had some trouble controlling his fast ball, though he apparently had a lot of good stuff on his curve. Interestingly, when he pitched he threw ambidextrously, right-handed to right-handed batters, and left-handed to left-handed batters. That inning he faced Jose Cardenal, who was his cousin, and forced him to pop out.

In the ninth inning Campaneris was behind the plate. The first batter was Ed Kirkpatrick, who got a single and stole second. The next two batters walked and flew out, which Kirkpatrick used to get to third. With the next batter, the Angels tried a double steal. Campaneris rifled the ball to Dick Green at second, who made the tag and drilled it back to Campaneris, who was about three feet from home plate on the third base side. Kirkpatrick ran straight for the catcher, trying to knock the ball out of his hand with the force of the impact, tumbling him down, but Campaneris held onto the ball, retiring the side.

He also leaped up, ready to duke it out with the larger Kirkpatrick, but other players kept them from exchanging any more than a couple of shoves.

After the ninth inning, Campaneris left the game and was taken to St. Luke’s Hospital for x-rays. He couldn’t play for several days.

Bert Campaneris was the first player in the modern major leagues to achieve the feat, but since that game in 1965 the 9 in 9 club has grown to include César Tovar of the Twins, Scott Sheldon of the Rangers, and Shane Halter of the Tigers.

I still haven’t determined whether Charlie Finley ever filed a claim for the insurance money.