The third man wanted $5,000 for the painting. As the article in the Star on March 17 put it, the third man also “wanted confirmation within 48 hours that the insurance company was willing to pay. Otherwise the deal was off.”

Stokstad and Bernstein contacted both the insurance company and the FBI, and the insurance company quickly agreed to pay the $5,000. But the Spencer people decided first to counter with an offer of $4,000—a stall with the aim of getting the FBI more time.

The counter-offer made its way through Brown and the lawyer and the acquaintance. The third man quickly turned it down.

This started a long exchange between the two sides—the museum wanting to make sure that the painting being offered wasn’t a fake, the third man insisting on the $5,000.

It dragged on for weeks, sprawling through September and mostly October, when Brown had to go out of town on business. Stokstad and Bernstein remained anxious throughout this stretch, afraid that the third man might give up, or get scared, or finally just destroy the painting. The FBI pretty much ran things for the Spencer, and this simply added to Stokstad’s and Bernstein’s anxiety, as the negotiations had already cooled in the days before Brown left town. And the third man seemed to be getting antsy—ignoring prearranged calling times and not accepting any of the suggested ways of effecting the transfer of the money and canvas.

The exchanges broke off.

Actually, they had stopped earlier, before Brown’s business trip. The first man, a criminal lawyer, said he had not heard from his contact. He also said he was helping out of “a respect for art” and he was not accepting a fee for his work on this case. The FBI watched him, and the government started applying some ... persuasion ... techniques. The lawyer finally, grudgingly, named his contact—a friend of his secretary.

When the FBI questioned the second man, he claimed not to be sure of the name of the third man. They had been inmates at Folsom Prison at the same time, but the second man said he couldn’t remember the third man’s name. Whitney? Or, was it Basher? Maybe ... Basham? He said he wasn’t sure. He did tell the FBI, though, that the third man contacted him for the first time on August 31st.

Making a long distance phone call on the road was much more difficult in 1962 than it is now, half a century later. There were no cell phones, so you’d have to find a public phone booth (unless you were rich enough to have a phone in your car, like Perry Mason). And you’d have to carry a substantial amount of change, since you wouldn’t want to make this particular call collect. And the law funding the interstate highway system had only been passed six years earlier and would not be pronounced as completed for another 30 years—driving halfway across the country took considerably longer in 1962 than it does today.

So, if the third man contacted the second man on August 31, after getting to California, the very latest he could have stolen the Manet painting would have been on August 29.

The FBI had leads now, and began narrowing in on their target.

On the morning of January 15, 1963, the Kansas City Times had a page one story about the recovery of the painting the previous day. The story was titled “Lost K.U. Art Work Is Found,” and part of it read—

The $40,000 Manet portrait missing since August 31 from the University of Kansas Museum of Art was recovered here yesterday by FBI agents.

The agents arrested William R. Basham, 31 [some newspapers put his age at 30], of Santa Monica, Calif., on a federal warrant charging him with receiving stolen goods.

FBI agents said the picture was in his home.

Upon hearing of the arrest the night before, KU officials had said that the insurance had not yet been collected. The painting was being held in FBI headquarters in Los Angeles.

William G. Simon, who headed the investigation for the FBI, declined to answer when asked what had led to the arrest—other than to say that they had been investigating the information that led to Basham for some time. (This would not be the only time that Simon’s name would appear in the national press in relation to a high profile crime during 1963.)

The FBI had raided the suspect’s apartment on January 14. After arresting Basham (an ex-con who had recently moved back to the California after leaving a job in New Orleans), the agents found what they had been looking for. Basham had laid the painting between two pieces of cardboard, which he had then secured with a safety pin and hidden on the shelf of a closet.

Basham protested his innocence. He hadn’t heard anything about the theft of the painting. He had been out walking and had just found it on the sidewalk. He insisted that he had never been within even a hundred miles of Lawrence.

The FBI started pursuing that claim.

Stokstad was relieved that the painting had been recovered. Throughout the negotiations she and Bernstein dealt with the dread that the thief might decide the authorities might be getting too close and simply decide to destroy the evidence and eliminate the painting completely. She was also relieved when initial reports indicated that, other than the cutting of the painting from its frame, the Manet was unharmed. (This would later prove to be inaccurate, as expert examination showed that the canvas had suffered twenty some abrasions.)

On Thursday, January 24, a federal grand jury indicted Basham on charges of receiving and concealing the Manet. Not able to meet the $500 bond that had been imposed, Basham was remanded to the county jail, still maintaining his complete ignorance of the crime.

A little over two weeks later, on Lincoln’s birthday, the hunch of one of the FBI agents working the case paid off. Bigtime.

Knowing that it was a huge longshot, the agent started going through the traffic tickets that had not yet been processed by the Lawrence police department, which were filed by the state shown on the license. If the agent had just started going through the states in alphabetical order, it would have taken him a long time. But if he worked off the fact that Basham had left New Orleans shortly before the theft, he probably found the evidence fairly quickly, because one of the first tickets in the Louisiana file had Basham’s number.

It was a parking ticket dated August 27, 1962. It had been issued at 1:00 that afternoon—one block from the Spencer.

When the prosecutors told Basham about the ticket, it didn’t take him long to change his plea to guilty.

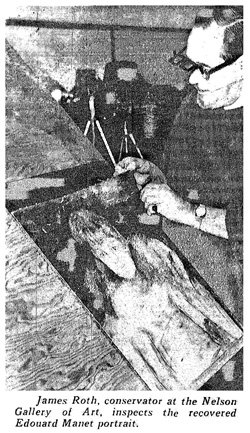

After the guilty plea the way was cleared for the Spencer to get the painting back. Before it returned full time to its home, the Manet got to spend some time close to its sister painting. It was handed over to James Roth, the conservator at the Nelson-Atkins, who set about restoring the work, which had lost chip of paint when Basham had rolled it up.

(I mentioned earlier that this was not the only nationally famous case that William Simon oversaw in 1963. On December 8, in Las Vegas, just two and a half weeks after the assassination of President Kennedy, Frank Sinatra, Jr., was kidnapped while his father was filming Robin and the Seven Hoods. Simon headed the FBI team that captured the kidnappers.)

Stokstad sent Bernstein to Los Angeles in early March to bring the painting back to Kansas. After filling out and signing a huge number of forms, Bernstein oversaw the packing of the painting. The Kansas City Star article that appeared on St. Patrick’s Day reported that the canvas was packed “between layers of form rubber held rigid by masonite slabs. A carrying handle then was attached to the masonite.”

As Bernstein was leaving the Los Angeles County Museum, a guard stopped him and asked what he was carrying, then called the County Museum director to clear Bernstein to leave.

Bernstein thought he probably surprised the guard for thanking him so many times for doing such a good job.

He may have been hoping the new guards hired by the Spencer would do as well.