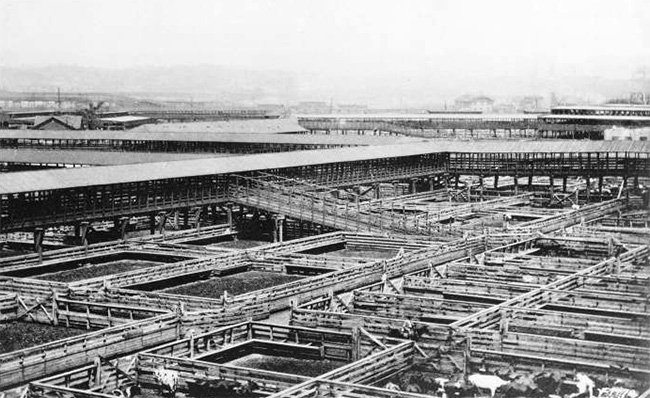

Kansas City claimed a population of just 4,418 in the 1860 census. With the opening of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869, and the arrival of the cattle trade and development of the stockyards, the city exploded onto the world stage, boasting the second largest livestock market in the United States and a population of over 160,000 by 1900.

But how did this come to be?

In some ways Kansas City’s progression was natural and organic, the city being a central point between cattle ranches in the Southwest and West and livestock markets in the East. Its location at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers played a part in Kansas City becoming a major transportation hub.

But location alone cannot explain its explosive growth. The people who lobbied for, invested in, and worked in the Kansas City livestock industry deserve credit for making the city what it is today. There were numerous individuals who saw the potential for Kansas City’s development and labored at molding the West Bottoms into a booming industrial district. It would be impossible to name all those who profoundly impacted the stockyards – eastern investors, local businessmen, cattlemen and ranchers, and immigrants who migrated to the West Bottoms all had a part in the success of Kansas City’s flagship industry.

For many of these individuals, few records remain to tell their stories. What sources can be found, however, point consistently to the determination and enthusiasm they had for helping Kansas City and the stockyards reach their potential.

That story begins with Joseph G. McCoy, perhaps one of the most important and tragic figures in the Kansas City Stockyards’ development. He played an enormous role in shaping the route of cattle being shipped from Texas to eastern markets, convincing Texas ranchers to drive cattle to Abilene, Kansas. There, they were shipped east by rail through Kansas City and over the Missouri River with the help of the new Hannibal Bridge.

In his book, Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, McCoy states that the success of the Abilene enterprise “was nearer and dearer to him than life itself.” Though he had made a deal with the Kansas Pacific Railway to get a part of the profit for initiating the contact between the railroad and Texas cattlemen, his contract was based solely on good faith. McCoy fought this in court and eventually received a payment from the Kansas Pacific Railway Company, but by then he was bankrupt and without the business he had built. The settlement he received was, as he put it, “like giving a loaf of bread to a man already dead from starvation – a very good thing to receive, but entirely too late.”

All accounts of McCoy place him as an honorable and trustworthy man, which seems to have led to his downfall. Though he had reason to be bitter with the railroad companies, he “felt that he had lost his money in an honorable effort to develop a worthy, legitimate enterprise.”

Today, he is celebrated for his actions in advancing the cattle industry in Kansas. But in 1915, he died rather poor and forgotten.

Eastern business investors and railroad magnates saw the potential in Kansas City, and interest swelled in making it a point of transfer for cattle over the Missouri River and on to eastern markets. L.V. Morse, Charles Francis Adams Jr., and Charles Fessenden Morse were just a few of the early organizers, investors, and managers of the Kansas City Stock Yards Company. Cuthbert Powell, in his Twenty Years of Kansas City’s Live Stock Trade and Traders, described L.V. Morse as “the moving spirit” of the stockyards, the first to organize a livestock trade in Kansas City by fencing off an area of land, building pens, and implementing a system of Fairbanks scales.

In 1876, Adams became president of the newly reorganized Kansas City Stock Yards Company, a position he held until 1902. Adams had strong connections to eastern capital, and brought in many investors to the stockyards cause. Charles Morse joined the stockyards action in 1879 at the behest of Adams, who appointed him general manager. With his help, the stockyards became Kansas City’s leading industry. Morse became president of the Kansas City Fat Stock Show Association when it was formed in 1882, was named president of the first Livestock Exchange in 1886, and succeeded Adams as president of the Kansas City Stock Yards Company, serving until 1913.

Meat packing magnates soon realized the benefits of moving plants closer to the cattle, where the animals could be slaughtered before a long and costly rail ride east.

The first packing houses in Kansas City were small, locally owned businesses with little long-term success. In 1870, Philip Armour, a partner in Plankington and Armour in Chicago, opened a plant in Kansas City with the help of his brothers. The Armour family, the first successful meat packing operators in Kansas City, helped spur the advancement of the livestock industry by creating the connections and demand for a growing stockyards complex. The refrigerator car and the ability to ship dressed beef resulted in further growth.

The Kansas City Star described the new Armour plant (1892) as the “largest business in Kansas City and employing over 4,000 people by 1901.” Other noticed its success, and eventually each of the “Big Four” (Armour, Wilson, Cudahy, and Swift) had plants in Kansas City, furthering the city’s “cowtown” reputation.

Charles Morse stepped down as president of the Kansas City Stock Yards Company in 1913 and caused a reorganization of the company’s leadership. George Richard Collett was hired as vice president and general manager, and brought ambitions for completely modernized facilities. Between 1913 and 1919, he rebuilt the entire complex. The American Royal Building (1922) also can be attributed to his improvement initiative.

One of the worst disasters to hit the West Bottoms came during this phase in 1917, when a fire raged through the stockyards. But before the flames had died down, Collett was making plans to rebuild what was lost. Under his leadership, the livestock market was unaffected by the chaos of the fire and remained open for business.

In 1918, Collett temporarily left Kansas City to fill in as vice president of Morris and Co. in Chicago in the absence of Col. Nelson Morris, who had volunteered for service in World War I. When Morris returned to Chicago in 1921, Collett was offered the job of president of the Kansas City Stock Yards Company and remained in the post until shortly before his death in 1942.

The people involved in the Kansas City Stockyards were passionate about what they did and worked hard to see it thrive. Accounts of these men, though limited, rarely failed to point out their determination to develop and grow the livestock industry. The Kansas City Stock Yards Collection, recently donated to the Missouri Valley Special Collections, highlights the development, growth, and legacy of the stockyards by giving us evidence of the land acquired, the facilities built, and the improvements and expansion of the stockyards complex.

Though this collection adds depth to what we know of the Kansas City Stockyards, a full account of the people who loved and lived the livestock industry remains a missing piece to the story.

References:

Charvat, Arthur. Growth and Development of the Kansas City Stock Yards: A History, 1871-1947. Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library.

Conrads, David. Biography of Charles F. Morse (1839-1926), Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library, 1999.

“History of the Kansas City Stock Yards,” Hereford Swine Journal, May-June 1914.

“K.B. Armour Is No More.” Kansas City Star 28 Sept. 1901.

Kansas City Stockyards Company, 75 Years of Kansas City Livestock Market History, 1871-1946. Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library.

McCoy, Joseph G. Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest. Edited by Ralph P. Bieber. Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1940.

Pate, J’Nell L. America's Historic Stockyard: Livestock Hotels. Fort Worth, TX: TCU Press, 2005.

Powell, Cuthbert. Twenty Years of Kansas City’s Live Stock Trade and Traders. Kansas City, MO: Pearl Printing Co., 1893.

Renner, G.K. The Kansas City Meat Packing Industry Before 1900. Missouri Historical Review, October 1960: 18-26.

Shortridge, James. Kansas City and How It Grew, 1822-2011. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2012.