By the time this particular blog gets posted, the Missouri Valley Room’s exhibit of charcoal drawings of Confederate guerillas who operated here in the border area of Missouri and Kansas during the Civil War—bushwhackers like Frank and Jesse James, Joe Lea, Cole Younger, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, and William Quantrill—will probably have been up for a week or two.

These drawings were donated to the library around 1980, but we have no record of their provenance—that is to say, we don’t know where they came from. We don’t know who originally owned the drawings, who commissioned their creation or why, or the exact date they were made (some of the drawings have the number “93” in the lower right hand corner, and the educated guess that this means those particular drawings were executed in 1893 is probably correct).

If the information about who donated the drawings to the library was ever recorded, it has disappeared during the nearly three and a half decades since.

We can verify that several of the drawings were based on photographs from the post-Civil War era, since many of those photographs have been used in books and articles, and even more can be readily found on the internet. Most, but not all, of the drawings have the name of the subject handwritten somewhere on the paper, and the writing for those names is noticeably different from the handwriting of the signatures of the artists. Based on the signatures, we know there were at least two artists, and probably only those two, since the unsigned drawings have strong stylistic similarities with one or more of the signed works.

So, we knew the names of the two artists—Elmer Stewart and A.L. Dillenbeck. When Eli Paul, who heads up things here in the Missouri Valley Room, and Kate Hill, who is one of the MVR librarian/archivists, started work on putting together an exhibit inspired by the drawings, we had no idea who Stewart and Dillenbeck were. We didn’t know what Dillenbeck’s initials “A.L.” stood for—we didn’t even know whether this artist was a man or a woman. We had a rumor that Dillenbeck was female, that the “A” was the initial letter for Annie or Anna, but these were far from verified, and we didn’t know whether the rumor had been attached to the collection from the start, or might have sneaked in sometime later.

This was how things stood when Eli came to me this spring with an assignment. On three separate occasions since the drawings had come into the library’s possession, different people had tried to track down information about Stewart and Dillenbeck. With no success. Eli asked me to take one more shot to see if I could find anything to identify these two artists. There wasn’t a huge rush—if I could find anything at all by the end of May he would be happy.

I had a few things I had to finish up the next day. The day after that, in the afternoon, I started my search.

The biggest challenge in doing research like this—well, any research, really—is figuring out where to look.

Here in the Missouri Valley Room we have different indexes that we regularly use. The two that are most handy are attached to the search engine on the department’s website. The first database is the Local History Index, which is continually updated by the librarians in the department who each have several periodicals that they regularly index, as well as the Kansas City Star, for which they are assigned specific weekday editions.

The other database is the Images index, in which the majority of the images owned by the MVR—photographs, post cards, maps, drawings, etc.—are either accessible in scanned form, or at least described.

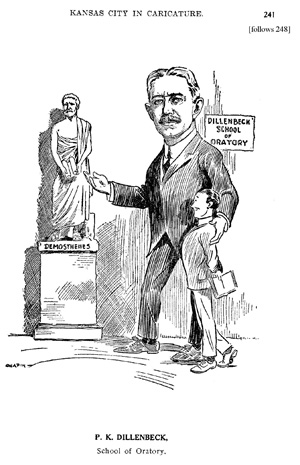

When I used the LHI/Images search engine, the first things I brought up were the things we already knew. It brought up the scans of the charcoal portraits that were signed with Dillenbeck’s name, or attributed to him/her. There was also a citation for a cartoon of someone named P.K. Dillenbeck in the book, Kansas City in Caricature. It had been drawn by R. L. Lambbin, one a several contributors to the book. P.K. (the P stood for Preston) ran, of all things, a school of oratory in Kansas City in the early 20th century, and must have been fairly successful at it. You didn’t make it into Kansas City in Caricature, by being just an everyday, ordinary person.

In using the LHI, I found that, with the exception of the few things about Preston K. Dillenbeck, the only hits I got led me back to the drawings themselves.

So, I needed to expand my search.

The website for Missouri’s Secretary of State has online search engines for death certificates of people who died in Missouri—one for deaths that occurred before 1910, and another for deaths that occurred from 1910-1962. Again, none of the hits for Dillenbeck matched the initials A.L.—which doesn’t necessarily mean that A.L. wasn’t a resident of Missouri at time of death, only that if the death took place by 1962 or before, he or she had probably been in another state.

There were about five hits for Elmer Stewart. All but two of them, though, were far too young to be our man. One of these was Elmer C. Stewart, who died in Atchison County in the middle of August of 1936. He had been born in Ohio on April 30, 1864, so he would have been 29 in 1893. Elmer C. had been a farmer.

The other one had no middle initial on his death certificate. He was born in Iowa on April 3, 1869, and died in Bates County on November 27, 1956. He had worked as a postal clerk in the U.S. Postal Service, and would have been 24 in 1893.

Interestingly, both of these men’s fathers had been named William.

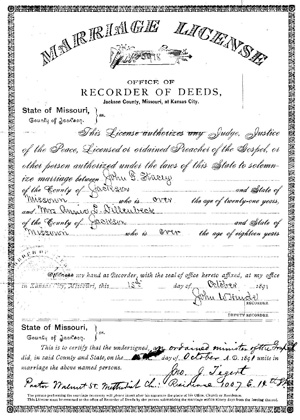

Another of the online resources we use a lot can be found on the Jackson County website. It’s one that I use a lot. It has scanned copies of, presumably, all the marriage licenses/certificates issued by the county that have been returned in their completed form. Obviously, this is an ongoing concern for the county. The really old ones take the form of entries in a ledger. I have used this database many times to find the names of the spouses of people I have been researching (as well as finding the marriage licenses of people I know). There is often a wealth of information to be found in these records. At the very least, it can point you to places for further searching.

Since Stewart is a much more common name than Dillenbeck, I decided to start with the latter.

Again, not knowing if A.L. was a man or a woman, I entered “Dillenbeck” as the surname of the groom. I got one hit, for a Ralph Dillenbeck who married an Elsa L. Somers on August 22, 1918.

Nothing directly applicable there.

So, I clicked on a new search, and entered “Dillenbeck” as the surname of the bride.

I got four hits. And the very first listing, reporting a marriage to a man named John F. Stacey on October 15, 1891, was for a woman named Annie L. Dillenbeck. (Well, they took out the license on October 15, 1891. The space for the date of the marriage had something written in it, but this has been blotted out with two large blots, and the county records give the date of marriage as October 15 as well.) The wedding was performed by Rev. John J. Tigert, who was pastor of the Walnut Street Methodist Church, and lived at 1007 E. 14th Street.

Bingo!

I had found an A.L. Dillenbeck! But was it my A.L. Dillenbeck?

I had an Annie L. Dillenbeck married to a John F. Stacey in 1891. Could I find any other mention of them?

The library has subscriptions to many different online databases. One that gets a lot of use by patrons in the Missouri Valley Room is the one for Ancestry.com. This is a large, umbrella type database that allows the subscriber access to millions of different records. One of the most important Ancestry offerings for research here in the United States is the compilation of information and images from the Federal Census that takes place every ten years. Because the government wants to protect the privacy of those who have been listed in the census records, they wait 70 years before releasing any personal information. So, the most recent census that is completely available is the one for 1940. After 2020 they will start releasing the personal information from the 1950 census.

The census records are a snapshot of the United States that’s taken once every ten years, so historians can get a kind of time lapse movie of the nation growing up. Through the decades the questions that are asked have change bit by bit, but the basics would usually tell you who was the head of the household, the names of all the members of the household, their relationship to the head of household, their age, their occupations, their marital status, where they were born, where their parents were born, whether they spoke English, and whether they could read and write.

And when you use it at the library, through the link on the library’s website, you get full access to all of the Ancestry databases, and don’t have to pay for it.

Since the husband would have been considered the head of household in 1900, I did a search of the 1900 census using John F. Stacey, to find out where the couple was living when they were in the federal census for the first time as a married couple. Granted, it was under “Stacy” rather than “Stacey,” but it has not been rare for census enumerators, especially in older census records, to produce a very creative variety of spellings for names (just as it was not unusual for multiple brothers from the same family who went to different parts of the nation when they left home to end up using different spellings of the family name). And granted, John’s middle initial could be taken for an “L” (as the Ancestry folks have it indexed), even though there is a line crossing horizontally through the vertical stem. But it is noticeably different from the “L” that is the middle initial for Anna’s name, especially at the top. The ages in the census record reflect those one would expect from those recorded on the marriage license.

And, Anna’s occupation is listed as “Artist.”

And that’s when the floodgate opened up.