In the 1900 census, I found that John F. Stac[e]y taught in the Chicago school district, and that his wife, Anna, was an artist.

So I started searching the internet, using the terms “Anna L. Stacey,” “artist,” and “Illinois.”

I found that Anna L. Stacey had attended the Art Institute of Chicago, and that she became a highly regarded painter in the Illinois arts community. The online resources about Anna Stacey pretty much matched what I had already found—that she had been born in Missouri and had moved to Kansas City and had studied at the Kansas City Art Association and School of Design, where John Stacey had been one of her teachers. That they had gotten married and then moved to Chicago.

The only thing that didn’t match (other than the “e” in Stacey) was her maiden name. The Illinois information gave it as Dey (in some places listed as Day) rather than Dillenbeck. At first I wondered if perhaps they had just gotten it wrong. Then I wondered if Anna herself, when she began to become an artist of some note, had simply changed the information, perhaps for professional reasons, for the simple reason that Dey is more streamlined than Dillenbeck. In any event, the Dillenbeck part of her personal history seemed to be unknown to the arts community in Illinois.

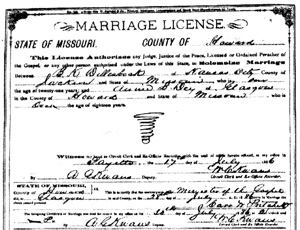

Then I looked at the copy of her and John’s marriage license with a little more care. Ah. On the form her name is written, not as “Anna L. Dillenbeck,” but as “Mrs. Anna L. Dillenbeck.” So she had been married before. Here in the Midwest, Dillenbeck is not that common of a name. I wondered if Anna had been married to Preston. Or, perhaps one of his male relatives?

I turned to our collection of city directories for Kansas City.

The 1891 directory (which would have been compiled before their marriage) lists John F. Stacey (or, more exactly, as it appeared in the directory, J. Franklin Stacey) as the “Principal” of the Kansas City Art Association and School of Design. (Illinois sources refer to him as the “Director.”) The school was in the Bayard Building at 1212-14 Main (where Stacey may have rented a residential room).

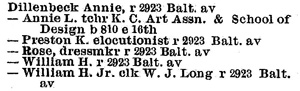

Anna lived in a boarding house at 810 E. 16th. Her occupation was listed as a teacher at the KC Art Association and School of Design. So, although she had been John’s student at one time, when they got married she was his colleague and not his student.

There was also a listing for a second Annie Dillenbeck (no middle initial) in the 1891 directory. This second Annie Dillenbeck lived at 2923 Baltimore Avenue, the same address listed for Preston K. Dillenbeck—as did Rose Dillenbeck (a dressmaker), William H. Dillenbeck, and William H. Dillenbeck, Jr. (who was a clerk at W.J. Long). The older William was Preston’s father.

I wondered if Anna L. Dillenbeck and Annie Dillenbeck might be the same woman. (Both are listed in various documents or directories as both Anna or Annie.) But our Anna and John were not listed in the 1892 directory, while the Annie at Preston’s house was. This other Annie continued to be listed in the city directory, moving after a few years. She eventually ran a book store.

I had started to think that I wouldn’t find anything specific about when Anna and John moved to Chicago. The 1892 Chicago directory I found online does not list them. The only time that I found when they were both listed in the city directory for Kansas City is the already mentioned 1891 edition. Then this morning, as I revise this, I had an idea, and I checked the voter registration lists for 1892. One John Stacey registered to vote in Illinois on October 18, 1892. I was excited, and thought I had our guy ... but the record gives his state of birth as New York, and the census records show Anna’s husband was born in Maine. This disappointed me, because the timing fit my preconceived ideas so nicely. So, the hunt continues on this one.

Tracking down Anna’s first husband took a while, but I finally found the information. Some of the material I found online about Anna’s career after the move to Illinois (particularly at the site for the M. Christine Schwartz Collection) provided the information that she had been born in Glasgow, Missouri. Glasgow is a small town about 30 miles WNW of Columbia, Missouri. In the 2010 census the population was put at just over 1100 people. Though a small town, it is actually in two counties—Howard on the south tip and Chariton to the north.

Anna grew up in the Howard County part of Glasgow. We may never know how she and her first husband met—she may have moved to Kansas City when she came of age. In any event, at some point she and her first husband met, and, on July 17, 1886, they went to Fayette, Howard County’s county seat, and filed for a marriage license. The clerk wrote down the groom’s initials as B.K., instead of P.K., but got Preston’s place of residence as Kansas City.

Anna and Preston got married July 28, 1886.

So far I haven’t been able to find when they got divorced, or where, or why. I do know that in less than six years after they married they had divorced and each had gotten married to a second spouse.

Both appear to have made better second marriages.

Preston taught at Kentucky University (what is now Transylvania University) during 1890-1892. (My thanks to Nancy DeMarcus and B.J. Gooch, librarians at the University of Kentucky and Transylvania University respectively, for their help in verifying this.) Anna and John got married in October of 1891. Preston and Lillie Lovette Lash married in July of 1892 in Linn County, Missouri. Preston’s name continued to appear in the city directories for 1891 and 1892; in 1891 his occupation is listed as “elocutionist,” and in 1892 no occupation is listed, so it appears he maintained the house for his father and siblings to live in while he was in Kentucky.

If Anna and Preston had not already officially separated by the time he moved to Kentucky, they certainly had separated and divorced before he returned to Missouri. The fact that Anna did not marry John Stacey until October of 1891, suggests she may have been waiting till then for her divorce to become final. Here’s a scenario that could fit the facts that we know.

Let’s assume that Anna and John were teaching at the school for the 1891/92 school year, and that they moved to Chicago during the summer of 1892. Anna could have continued to work on the drawings during the remainder of that school year, not getting the entire commission completed before she left. It is possible that she may have received the commission for the drawings near the end of her enrollment as a student at the School of Design; this may have even been one factor in her being hired as a teacher there. If, in fact, the school offered her a teaching position for the fall of 1890, this may have been the main reason she did not go with Preston to Kentucky. (I am still hoping to find the legal papers on the divorce.)

We don’t know when Anna and John fell in love with each other. There may have been an attraction while she was still his student. Or, once she and Preston had separated, the respect that student and teacher had for each other may have slowly transformed into love between two colleagues. Anna and John got married while Preston was still in Kentucky. Some nine months later, he had moved back to Kansas City and remarried as well. It seems not unlikely to me that, at the end of their 1892 responsibilities to the School of Design, John and Anna moved to Chicago, where John could teach, and Anna could attend the Chicago Art Institute. Perhaps she had been accepted earlier in the year, and that was the primary reason for their move.

The Elmer Stewart drawings in the collection have the number 93 under his name. Again, this almost certainly indicates that they were drawn in 1893.

Upon deciding to move to Chicago (and news of Preston’s anticipated return to Kansas City may have been a factor) Anna would certainly have informed the person who commissioned the drawings, that she would be leaving the area before she would be able to complete all the drawings requested. I can picture the commissioner, thinking that the School of Design would still be the best place to find an artist to continue the project, waiting till classes restarted in the fall before starting the search for Anna’s replacement. The narrowing down might have taken two or three months, and it could easily have been near the end of 1892 before Elmer Stewart was chosen and had started on his first drawings.

The above could also explain why some 13 of the drawings, all attributed to Anna, are unsigned. If these 13 drawings were ones she completed after she and John Stacey got married, her name would no longer be A.L. Dillenbeck. But that was the only name by which she had been known professionally. Perhaps she didn’t sign them because she was no longer A.L. Dillenbeck, but didn’t want to call attention to events in her personal life by signing them A.L. Stacey.

In any event, Elmer Stewart became part of the project.

Other than the drawings themselves, I have found nothing concrete about Elmer Stewart the artist. There were at least two or three Elmer Stewarts in the KC area during the time period. In the 1893 city directory, an Elmer T. Stewart lived at 1308 Lydia. He worked as a clerk for the Post Office. By the time the 1894 directory came out, this Elmer had moved to 3215 Holmes, and there was an Elmer E. Stewart, a bricklayer, who lived at 1520 Jackson. The bricklayer may be the same Elmer E. Stewart who married Louise Westmoreland in 1887.

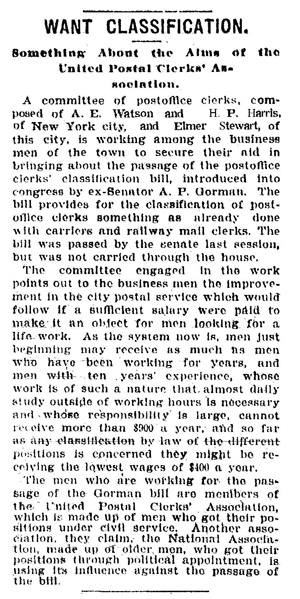

The postal clerk made page 7 of the June 21, 1899, edition of the Kansas City Journal, because he was one of three post office workers in the United States who were on a committee trying to get a post office clerks classification bill passed in the US congress.

It is possible that one of these Elmer Stewarts is the Elmer Stewart whose poem, “The Soul in Love,” was published in 1904 in the November issue of The Life, a “monthly magazine of Christian metaphysics” printed in Kansas City by A.P. (Abraham) and C.J. (Catherine) Barton, husband and wife. Catherine was herself an accomplished portrait painter, and she and Abraham were the parents of artist Ralph Barton, who would later gain fame in New York City as an artist and cartoonist with the New Yorker. While a teenager, Ralph Barton became a cartoonist for the Kansas City Journal, and one of the contributors to Kansas City in Caricature, though he was not the one who drew P.K. Dillenbeck’s caricature.

Sadly, we have nothing concrete about the artist known as Elmer Stewart, other than the fact that “Elmer Stewart” is the name signed on 16 of the drawings. I think that if the records for the School of Design had not been destroyed in a fire, we would probably find that someone named Elmer Stewart attended there. And, while I have no evidence to support this, I like to think that the poet Elmer Stewart who wrote “The Soul in Love” may also be the Elmer Stewart we are looking for, if for no other reason than the something inside an artist that needs to be expressed often seeks out more than one avenue.

So, what’s the upshot of all this?

Well, first and foremost, we now know who A.L. Dillenbeck was. Elmer may still be a cipher, but Anna has finally presented her calling card to us. She came from a small town, and, although we don’t know the order, came to Missouri’s second largest city and married Preston Dillenbeck, who was also associated with the arts. She attended the School of Design, she and Preston divorced, and she taught at her alma mater, married her former teacher, moved to Chicago, and became highly enough regarded as to achieve a solid standing in the art community of Illinois.

All of this has enriched this particular collection in more than one way. We know more of the story now. This is always a plus when you’re dealing with history. Elmer Stewart hasn’t told us who he is, yet. He remains a name—someone who had a native talent that, based on the drawings themselves, was not as polished as A.L. Dillenbeck.

We know A.L. Dillenbeck and Anna L. Stacey were two names for the same person at different times in her life and her career. Because Anna came to be an artist of some stature after she moved to Illinois, learning that she produced the drawings in our Confederate Guerillas collection fills in a big gap in her development as an artist.

I think it may appreciate the monetary value of the collection as well.

I also found that John and Anna remained strong supporters of the arts, and that Anna’s will provided for the John F. and Anna Lee Stacey Scholarship Fund for Art Education, setting up a trust fund “for the education of young men and women who aim to make art their profession.”

I wonder what else we might find.