On June 12, 1925, the lives of three men came together in a way that challenged how things had always been in Kansas City. Find out how a teacher, a student, and a reporter swung a hammer at the strong wall of ethnic tradition in KC.

William Levi Dawson was born in Anniston, Alabama, on September 26, 1899. Dawson had a special kind of musical genius, and it helped him create a fault line in one of Kansas City’s historic barriers.

Dawson was the oldest of George W. Dawson’s and Eliza Starkey Dawson’s seven children. George, who had probably been a slave, opposed the idea of his first born getting an education, let alone in the arts, and set up an apprenticeship for his son with a cobbler, so he could start contributing to the support of the family. Eliza, though, supported William in both his interest in music and education. While he was still young he heard about the band from Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, and decided that someday he would attend Tuskegee.

Dawson said in an interview conducted by Nathaniel C. Standifer that he became interested in music “at a very small age.” He recalled that the local band in Anniston “played once a year, played the emancipation proclamation.” He also mentioned a minstrel show that came through and that he and the other kids followed them around. He “used to love to see the trombone players in the first line throwing their horns from one side to the other.”

A distant relative gave Dawson his earliest music lessons, teaching him first the bass part “kinda like boogie-woogie.” Dawson appears to have turned to another teacher when the relative told him he didn’t need to learn to read music. The budding musician turned to S.W. Grisham, who was an excellent trumpet player and had been band master at Tuskegee. Grisham had a band of a little over a dozen players in Anniston, and Dawson wanted to join and learn. When he finally saved the money to buy a half brass, half copper trombone, his father told him he didn’t want him “to fool with music.” He turned to the mellophone (which looks like a flugelhorn, but with a bigger bell), which he had borrowed from Grisham.

Besides studying music with Grisham, Dawson also took lessons in reading, writing, and arithmetic (in secret) from a Prof. Carmichael for fifty cents a month. To pay for these lessons and save so he would eventually be able to make the trip to Tuskegee, Dawson, as he called it, “knocked down on” his father, who would take all that the boy earned and then give him ten or fifteen cents each Sunday for an ice cream cone. This is how Dawson explained the term—

I was shining shoes and if I made $3 I would take 50 cents and keep it for myself. We call that knocking down. I would give my father the $2.50 and maybe he would give me 10-15 cents.

A neighbor’s house had a floor that was “high up,” and Dawson would crawl under the house and hide the money in a snuff box. But when he checked at the end of the first year, someone had stolen the money.

Over the course of the next year Dawson saved enough money to buy himself a bicycle, which he used to deliver packages for a “very select women’s wear store. Facing his father’s opposition, Dawson still had to be secretive, hiding his music lessons from George, and in 1913, shortly before turning 14, he sold his bicycle for $6.00, and with his mother’s help bought a ticket, boarding the train for Tuskegee in the middle of the night at a junction, hiding in the men’s room of the colored car until the train was safely beyond where his father might find him.

At Tuskegee Dawson started classes in agriculture, earning the money to pay for his schooling by working in the fields during the day and then taking his classes in the evening. Work/study was the standard at Tuskegee, reflecting Washington’s philosophy of training the school’s students for future employment and self sufficiency. Life at Tuskegee operated on a strong schedule, everyone rising early in the morning and either working or studying until 9:30 at night.

Dawson loved his time at Tuskegee. It gave him focus, and in Washington he found an adult man who provided an amazing example. He also became a member of the school’s band.

Booker T. Washington died in November 1915, but in the short time that their paths intersected, this great teacher had a profound impact on Dawson’s life, and the young man who had so yearned for education joined the other members of the band processing behind the hearse.

Dawson was at Tuskegee for seven years. It would be tempting to assume that his future genius would immediately show itself, but Dawson had a great deal of work ahead of him.

When he first auditioned for the band (for which no credits were given) he did not do well, not being able to play “an eighth note followed by a quarter and an eighth in 2/4 time. Luckily for Dawson there was only one other trombonist (who was quite accomplished), so Professor Stanley Williams told Dawson to come back the next day and try again. Dawson went back to his room and studied Music Self Taught by J.W. Pepper. “I got up there and I just stared at those notes and analyzed those notes and studied that one rhythm and I learned how to count. I played that rhythm over and over.” When he went back the next day he was able to play the phrase, and Prof. Williams let him into the band.

All of the students at Tuskegee were required to take music. Besides Prof. Williams, Dawson studied under Jennie Cheatham Lee, who directed the choir. He later said, “I was so grateful to her because that is where I learned what we call soul today.”

While a student at Tuskegee he gained a lot of practical understanding of music. He learned to play almost all of the instruments, and during World War I, when one of the other teachers was called to active military service, Dawson taught some of his fellow band members their parts. He also worked in the band master’s office. He had turned into a pretty accomplished trombonist, and also was playing the euphonium.

In the summer of 1921 Dawson toured the Redpath Chautauqua circuit in the northeast and Canada with the Tuskegee Institute Singers. He was often featured as a trombone soloist.

He had graduated from Tuskegee that May. Kansas beckoned.

Dawson was offered, among many others, two positions as band master at schools in Kansas. The one that he accepted was in Topeka, at Kansas Vocational College.

The school had never had a band.

Dawson wanted more education, particularly in composition and orchestration, so he applied to attend nearby Washburn College. When asked for his credits, he told the people at Washburn that he had no academic credits, but if they were willing, he would appreciate it if they gave him an examination. Apparently his knowledge and experience impressed them enough that they enrolled him as a student—the only African American student in the music department.

That experience served Dawson well. He was able to perceive the challenges and work out the solutions far better than any of the other students. He particularly impressed Dean Sterns, who taught the composition class. At one point he presented the dean with the draft of a violin romance he had written, and the dean looked at the music and told him that the piece needed to end in the key in which he had started. A few days later, though, Sterns asked if Dawson had the music with him and took him to the chapel, where the dean played it for a small audience. Dawson later said it was so smoothly done that Sterns told him, “Now, Dawson, hereafter you write whatever you want to write.”

After that year Dawson moved to Kansas City, in part to begin teaching at Lincoln High School, taking the place of M. Clark Smith, who had been hired by the Pullman Company to create a large chorus from the over 1000 porters who worked for the company, as well as to develop a number of quartets of singers.

Dawson taught band, orchestra, and choir at Lincoln. Before he began working at the school, though, he went door to door, selling self-published copies of one of his early songs, “Forever Thine” for 25 cents, “all over Kansas City, Kansas, and Missouri.” He said no one ever turned him down.

In the Standifer interview he said he “was trying to get to Ithaca, New York, where Pat Conway the great band master was.” Patrick Conway, who is one of the great band leaders mentioned prominently in the song “76 Trombones,” opened the Patrick Conway Military Band School, affiliated with the Ithaca Conservatory, in 1922.

It’s not exactly clear when Dawson found out about the Horner Institute. It’s possible that he might not have been able to say. The Horner Institute had already become an important part of the Kansas City cultural scene, so it would be natural for someone like Dawson, with such a focus on music, to have heard about it early on after his move—if he had not already heard of it from one of the music professors at Washburn. He said later that he “had enough sense” to know that the Institute could offer the musical instruction that he needed.

So, “I went out to the Horner Institute and told them I would like to study.”

They told him no.

When he asked why, they told him, “Because you are a Negro. We don’t allow Negroes to attend class.” Dawson told them that he wasn’t particularly interested in attending the classes—he just wanted to study with some of the Horner Institute’s teachers.

I imagine this probably caught them (Dawson doesn’t identify who “they” were in the interview) a little off guard. It’s possible that Charles Horner himself was part of this meeting. It’s also possible that he and Dawson had made some connection before through the Chautauqua circuits. Or it’s possible that Horner and Dawson had heard of each other. Or they may have had no inkling of each other before this coming together.

What seems apparent is that the people at the Horner Institute were caught unawares by Dawson’s request. You didn’t play around with Jim Crow and the segregation laws. Not in Kansas City in 1921.

They told Dawson to “Come back in two or three weeks,” probably assuming that he would give up and not come back.

He didn’t give up.

He went back.

Learning what I have about Dawson while researching this story, I cannot picture him having gone the first time without having taken his trombone so he could audition. I also picture him taking “Forever Thine” and some of his other compositions. I picture him calmly presenting the sheet music and performing some pieces, and then sitting there quietly to see if they would let Jim Crow force them to deny the evidence of his talent and preparation.

It may not have happened that way, but that’s how I picture it.

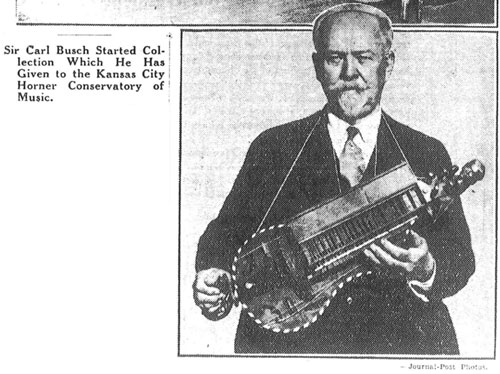

Carl Busch in the Journal Post, 1928

I also picture the sheet music going to Sir Carl Busch and Regina Guilmette Hall, the faculty members under whom he wanted to study. Busch was originally from Denmark and had come to Kansas City as a young man. He had become internationally known as a composer and conductor, and had been knighted by the Danish king. Hall had been born in New Hampshire to a father from Scotland and a mother from New York. She got her degree from the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, and became renowned for her teaching of harmony, and later writing textbooks on the subject. She had started teaching at the Horner Institute in 1917, and continued teaching in the different variations of the school for 31 years. At some point she was given the nickname of Mother Hall, possibly because about a year after the events covered here she took charge of the women’s dormitory at the school.

When Dawson returned to the Institute two or three weeks after his first meeting, the people he spoke with told him they couldn’t let him take classes with the other students. They did, though, offer him the alternative to arrive late in the afternoon and have one on one mentoring sessions with members of the faculty.

I picture a slight smile on Dawson’s face when he said that, actually, he would prefer it that way.

They told him he would have to wait until 3:00 each afternoon, after the school had closed. Since he was teaching at Lincoln each day, this arrangement would suit his schedule better, and he would receive personal instruction rather than being just one face among many.

He thanked them and asked when he could start.