Imagine driving through the West Bottoms on October 19, 1943, when the Kansas City Stock Yards (KCSY) Company set a world record by receiving 64,015 head of cattle in a single day. For perspective, in its first year of operations, 1871, the stockyards received a grand total of 120,827 head.

During those 72 years, the central livestock market in Kansas City had become increasingly essential to the economic well-being of many Americans. Today, many Kansas Citians know the significance of the old stockyards but could they describe its day-to-day operations? What exactly transpired at the stockyards besides a lot of manure?

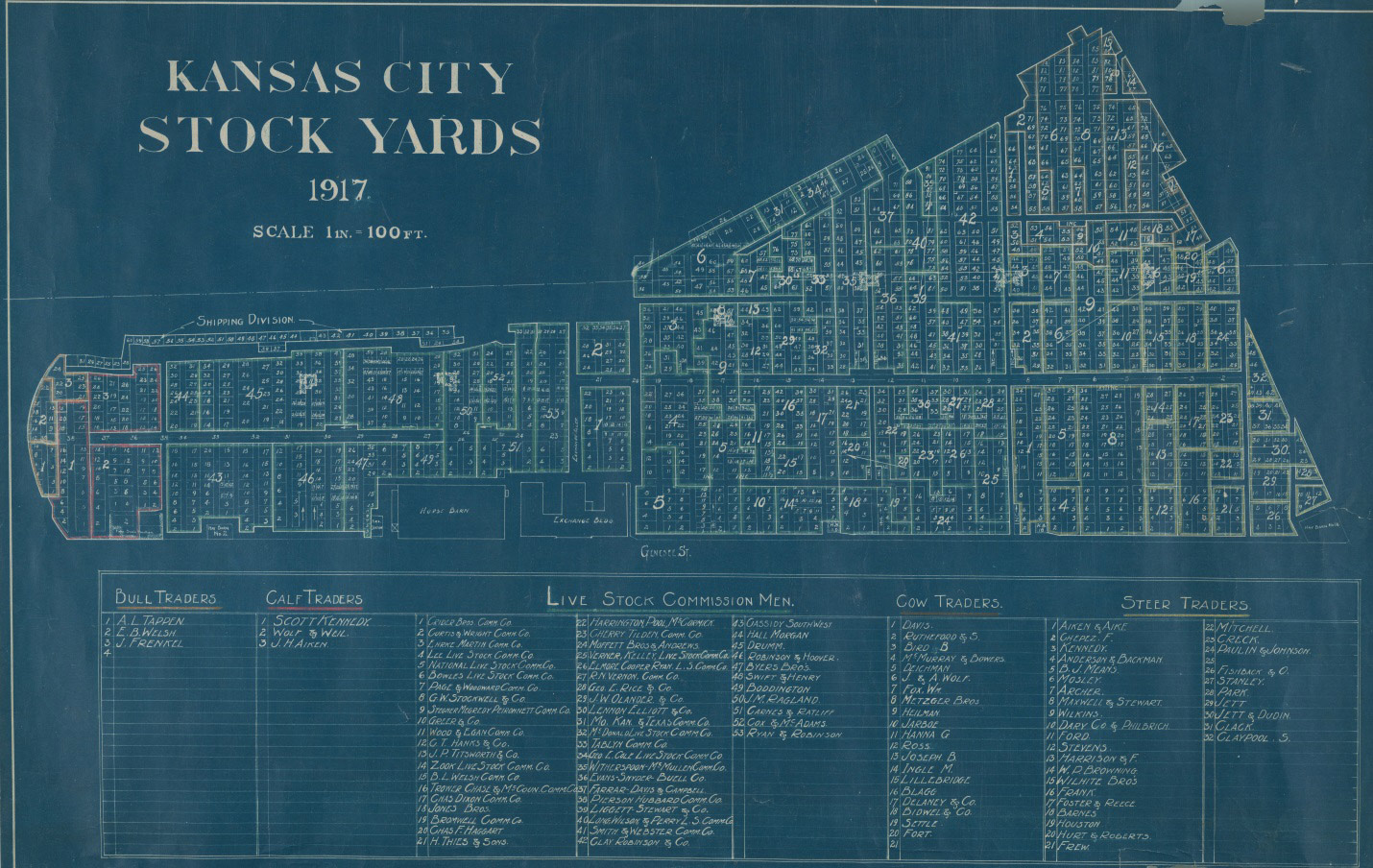

First, it is important to clarify that the KCSY Company did not buy or sell livestock but acted as a “livestock hotel,” a neutral marketplace where the animals could rest, feed, and be bought or sold by third parties. The stockyards made its profit through yardage fees, including costs for feed, water, weighing, and other service charges. Facilities for housing and transporting livestock through the yards were under frequent construction and repair in order to accommodate the large quantity of animals arriving daily. Examining historic drawings of the yards, one can see a vast maze of chutes, scales, cattle pens, sheep barns, hog houses, and horse and mule barns.

Livestock usually was brought to the stockyards by commission agents, or representatives of livestock producers. Other business interests included farmers, truckers, independent buyers, packing house buyers, and order buyers who purchased for distant customers.

Once livestock arrived, stockyards employees began an efficient process of driving the animals through alleys to their designated pens, where they were promptly fed and watered. Before trucked-in livestock became the norm, animals were unloaded from long stock trains onto platforms before being driven to the pens. Commission men sorted cattle into different sales pens by weight since mixing thin and heavy cattle would drive down the price.

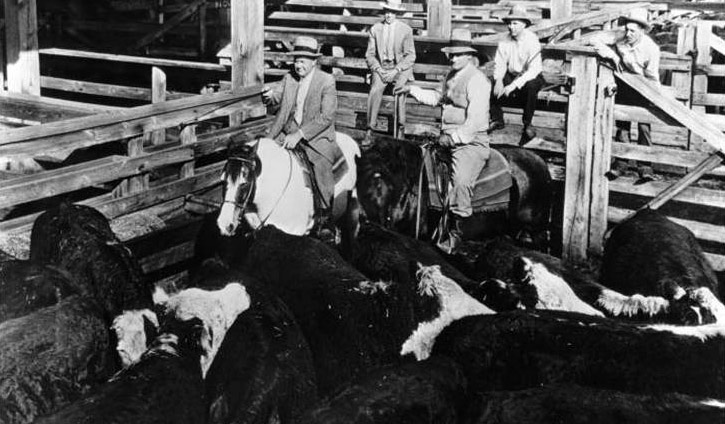

Prospective buyers, who would wait in the alleys until the market was open, stood on the fence boards of the cattle pens to survey the animals. If a buyer made an offer, the seller would either accept or make a counter offer. Written contracts were not used. Instead deals were struck with a “handshake and a man’s word,” as KCSY Company president Jay B. Dillingham once said.

After an agreement had been made, cattle were driven up ramps into the scale houses. There, they were weighed as a group by a stockyards scaleman before being transferred into the hands of their new owner. While commission men were in charge of their stock throughout much of this process, stockyards employees were ever-present, overseeing logistics, caring for the animals, counting livestock, and recording each shipment.

While livestock generally stayed at their “hotels” for an average of just 24 hours, many shipments arriving at the Kansas City Stockyards required special care and perhaps a prolonged stay. During the 1880s, the KCSY Company became the first to create separate yarding facilities for tick-infested cattle. West of the Kaw River, these quarantine yards were remodeled and renamed the West Side Feed Yards after interstate shipment of cattle ridden with ticks was forbidden by the Federal Government in 1928. Livestock being shipped from long distances could be brought to the West Side Feed Yards to rest, feed, and hopefully gain a few pounds before being put on the market.

After the Packers and Stock Yards Act of 1921, government agents also would become regular fixtures at the Kansas City Stockyards. While the Packers and Stock Yards Administration tested the stockyards for compliance, representatives from another agency—the Bureau of Animal Industry—enforced quarantine regulations and administered vaccines.

Occasionally, natural disasters and other calamities disrupted daily operations at the stockyards and endangered the livestock. The devastating floods of 1903, 1908, and 1951 and a particularly terrible fire in 1917 wreaked great havoc. The fire, which began near 12th and Genessee streets, caused nearly $2 million in damages, including a substantial loss of livestock. It killed 11,000 cattle and 6,000 hogs, and the ownership identity of 12,000 animals was lost. Unidentified animals that were not lost or stolen had to be auctioned to fulfill insurance claims.

Despite this setback, the central market continued to prosper, especially through times of war. During World War I, thousands of animals from the Kansas City horse and mule market were shipped to the British government. The stockyards were consistently busy during World War II, when demand for meat to feed the armed forces was high. About 40,000 head passed through the yards daily until that record-breaking day in 1943.

By 1946, the Kansas City market had shipped livestock to—or received it from—all 48 contiguous states and its contribution to the city’s growth and development could not be denied.

References:

Charvat, Arthur. Growth and Development of the Kansas City Stock Yards: A History, 1871-1947. Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library.

Coleman, Daniel. Biography of Jay B. Dillingham (1910-2007), Businessman. 2009.

Graham, Charles W. “Dock Riders of the K.C Yards.” The Kansas City Star, July 13, 1947.

Kansas City Stockyards Company. 75 Years of Kansas City Livestock Market History, 1871-1946. Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library.

Pate, J’Nell L. America's Historic Stockyards: Livestock Hotels. Fort Worth, TX: TCU Press, 2005.