There was a time when you could only watch baseball in sunlight. I grew up in Idaho during the 1950s and 60s. I’m sure I’m not the only person who remembers playing pickup midsummer baseball games that started late afternoon and continued through sunset.

By dusk, the game finally reached the point when the movement of the ball had become more of an inference than something actually seen, while parental shouts echoed throughout the darkening grey for the better part of half an hour, threatening unnamed consequences if we didn’t get ourselves home for supper this very instant.

By most accounts the first night baseball game was played on Nantasket Beach in Hull, Massachusetts, on September 2, 1880, starting at 8 o’clock. (Edison had perfected his light bulb the year before.) Northern Electric Company of Boston organized the game to advertise the use of electricity, featuring teams sponsored by two local companies. The lights were too weak, causing many errors. The game ended after nine innings and an hour and a half of play in a 16-16 tie so the teams wouldn’t miss the last ferry back to Boston.

During the rest of the 19th century a handful of other night games were played, most using electric light, but at least one used gas. None of these games seems to have been a rousing success.

After the turn of the century, through the first three decades, there were only a few night games played.

Then came October 24, 1929, and the stock market crash, and things started to change.

The Kansas City Monarchs had won the Negro National League championship in 1929, but had their lowest gate receipts in the history of the league. It was probably during this time that team owner J.L. Wilkinson began considering leaving the league and becoming an independent.

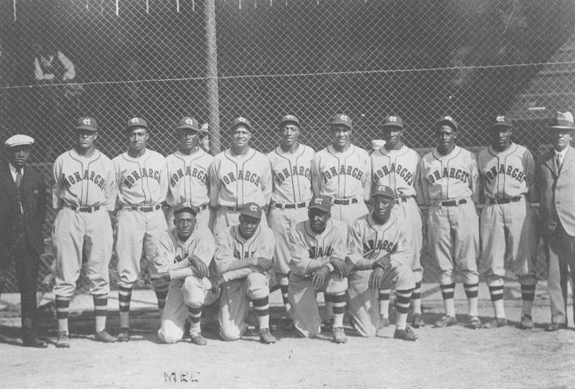

Kansas City Monarchs 1934 group portrait

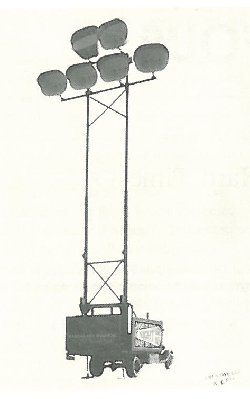

Wilkinson had experimented with night games earlier in his career. His earlier team, the All Nations, had played a gaslight game near Des Moines. Early in 1929 he decided to pursue a radical idea. He mortgaged most everything he owned, took Thomas Baird as a partner, and hired Omaha’s Giant Manufacturing Company to construct a portable lighting system, which cost between $50,000 and $100,000. (A 1929 dollar had the same buying power as $12.82 in 2011, so that would be between $641,000 and $1,282,000 today.)

The system had telescoping poles which extended 50 feet above the field. Pictures show a set of six floodlights atop each pair of poles. Derricks pivoted the poles into position above the truck beds to which they were secured. In her book, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball, Janet Bruce says that the Monarch’s lighting system took about two hours to assemble. The set-up included a huge generator that was placed in center field, made an enormous amount of noise, and “used fifteen gallons of gasoline every hour.”

1930 Kansas City Call newspaper headline

The team bus (more the size of one of today’s shuttle buses, with an exterior that looked something like the cross between a boxy station wagon and an SUV) was refitted to carry the motor and generator, and the players now traveled in a car.

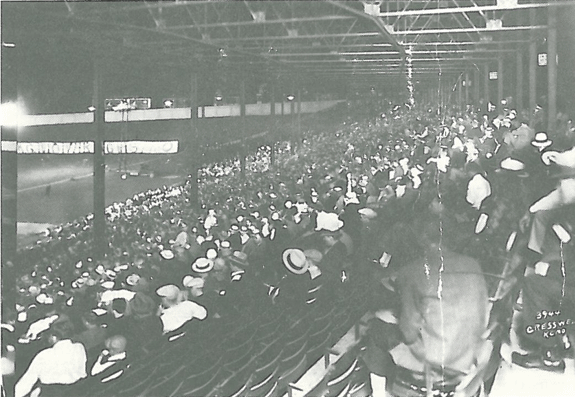

At first Wilkinson and Baird raised ticket prices, but soon found that between the novelty of the lights, and the much larger number of people who worked during the day but could now come to night games, lowering prices actually increased profits. If 3,000 fans showed up for a day game it was counted as a big day. With the advent of night games, 3,000 turned into the starting point, and attendance could reach 12,000 to 15,000.

Wilkinson's portable lighting system.

There were still problems for the players. Wilkinson’s lights, though many steps ahead of what had preceded, wouldn’t compare well with what we experience at Kauffman Stadium. They didn’t have near the height or the illuminating power that we are used to. With the lights only reaching 50 feet above the field, even a moderately high fly ball would disappear completely into the night. (This caused a limit to be placed on the number of bases allowed for a fly ball during night games.) Setting the generator with its wiring in the outfield, along with the poles, increased the number of obstacles the fielders had to navigate.

The lighting system had another impact on the team—once regular night games became part of the Monarchs’ schedule, their season didn’t start until about a month and a half after the rest of baseball. Wilkinson found that renting his lighting system out to other teams for their night games not only gave him breathing room to meet the payments on the lights, but actually went a long way towards ensuring that he ended each season comfortably in the black. So, the Monarchs delayed the start of their season to allow other teams to rent the equipment for their night games.

The House of David was one of the major users. It was a religious community that began in 1903, emphasizing participation in sports, particularly baseball, for physical fitness and development of spiritual discipline. Shortly before World War I, their team started competing against other teams and, in short order, barnstorming around the country. With increasing competitiveness, they used players outside the community. Satchel Paige spent some time with them, and Grover Cleveland Alexander became their manager.

The House of David rented Wilkinson’s lighting system to play night games during the early months of their barnstorming season. In time the two teams developed a working relationship that included Thomas Baird doing the booking for both. Sometimes they coordinated barnstorming tours so first one team would route through a state, playing all the local teams, and then the other would follow along the same route. Since the Monarchs and the House of David had great baseball talent, both usually defeated the local teams. When the second team finished the route, they joined and worked their way back along the same route, playing each other.

This August marks the 81st anniversary of perhaps the earliest great night game. On August 2, 1930, the Monarchs hosted Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays at Muehlebach Field for a game under the lights. Chet Brewer pitched for the Monarchs and “Smokey” Joe Williams for the Grays. A young Josh Gibson caught in his first game for the Grays.

A 1930 night game in Muehlebach Stadium at 22nd and Brooklyn. Photo courtesy The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball by Janet Bruce

Gibson went hitless for three at bats. He had a lot of company. On both teams.

Both pitchers had shutouts going into the 12th inning. Williams gave up one hit, while striking out 27. Brewer struck out 19, and gave up four hits. Unfortunately for the Monarchs, the last of those drove in the only run of the game.

The importance of night games to baseball continued to grow.

It took the major leagues another five years to schedule regular night games. Meanwhile, more and more minor league teams installed lights. And the Monarchs were not the only barnstorming team to use them.

An interesting thing happened. Minor league teams, dealing with the Depression, and recognizing the income potential of both night games and broadening their fan base, started playing more games against Negro League teams—games that were acknowledged and not hidden from public view. Barnstorming teams following the House of David, started to integrate.

Baseball slowly started to change its understanding of the term “national pastime.”

Books on the Monarchs and the Negro Leagues in the Missouri Valley Room—

Bruce, Janet, The Kansas City Monarch: Champions of Black Baseball

MVSC 796.357 B88K

Hauser, Christopher, The Negro Leagues Chronology: Events in Organized Black Baseball, 1920-1948

MVSC 796.357 H37N

Heaphy, Leslie A., ed., Satchel Paige and Company: Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, Their Greatest Star and the Negro Leagues

MVSC 796.357 P14ZHE

Irvin, Monte, Few and Chosen: Defining Negro League Greatness

MVSC 796.357 I72F[>

Lester, Larry, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: the 1924 meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs

MVSC 796.357 L646BF

Lester, Larry, Black Baseball in Kansas City

MVSC 796.357 L64B

Posnanski, Joe, The Soul of Baseball: a Road Trip Through Buck O’Neil’s America

Browsing MVSC 796.357 P58S

Ribowsky, Mark, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues

RAMOS 796.357 R48C

MVSC Vertical Files—

- Baseball—Monarchs

- Buildings—YMCA—Paseo

- Museums—Negro League Baseball

- O’Neil, Buck

- Paige, Satchel