A little before 11 p.m. on Thursday, January 3, 1935, Robert Lane was driving on 13th Street. Lane worked for the Kansas City water department. He later said that as he drove he noticed something rather strange. As he approached Lydia avenue, he saw a man was running west on the north side of the street. This man was clad in trousers, shoes, and an undershirt. That’s all. Though the day had been pretty mild by January standards, he must still have felt chilled.

He waved and shouted to Lane to stop. He approached Lane’s stopped car, but slowed, furrowing his forehead. He apologized, saying, “I’m sorry. I thought you were a taxi,” then looked up and down the street. “Will you take me to where I can get a cab?”

Lane nodded, and replied, “You look as if you’ve been in it bad.”

The man grumbled, “I’ll kill that—” (here the Times printed a long dash to indicate a deleted expletive) “… tomorrow,” as he opened the door and got into the back seat.

Lane glanced at the man, shifted gears, and headed his car toward 12th and Troost. He stared quietly at the man through his rearview mirror, noticing a deep scratch on his left arm. He also noticed that the man cupped his hands. Lane thought that the man might be trying to catch blood from a wound more profound than the scratch on his arm.

As the car approached the desired intersection, the man thanked Lane as he jumped out, then ran to the driver’s side of a parked taxi, opened the door, and honked the horn. Very quickly the cabbie could be seen hurrying from the restaurant where he had been eating.

Lane drove off.

In that first week of January 1935, future world heavyweight champion boxer Floyd Patterson was born in Waco, North Carolina. Bob Hope made his first appearance on national radio. The dry forces in Missouri announced that they would limit their efforts to lobbying the state legislature to pass a bill granting individual counties the authority to declare themselves liquor free. That first week, President Franklin Roosevelt informed Louisiana and its U.S. senator, Huey Long that federal funds would be withheld as long as Louisiana continued to observe the dictatorial state laws that that Long had pushed through the legislature while governor. Roosevelt also went to Congress and delivered his second State of the Union address.

Kansas City newspapers carried announcements that the son of the U.S. Secretary of War would marry the daughter of a bricklayer, and that the daughter of Missouri’s Lt. Governor would marry an Italian nobleman. Amelia Earhart was preparing to be the first person to fly non-stop from the Hawaiian Islands to California.

There was plenty of crime-related news being made that week as well.

In Topeka, Gov. Alf Landon called for modernization of methods of coping with Kansas bandits, pointing out what could be accomplished by a statewide law enforcement organization in driving out the criminal activities of the growing number of bandit gangs, who used the speed of automobiles to evade the jurisdictional limitations of local police.

In Flemington, New Jersey, the Bruno Hauptmann trial for the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby was producing daily headlines throughout the country. The jury at Kansas City’s Federal Courthouse found all four of the men accused in the Kansas City Massacre case guilty of conspiracy to cause the escape of a federal prisoner, and Judge Otis gave what some considered fairly light sentences.

On Wednesday, the second day of the New Year, a lone man, carrying no luggage, entered the Hotel President at 14th and Baltimore, four blocks from the Central Library. He apparently had one of those faces that different people read in different ways. One account gives his age as 20-25, another 25-30, and yet another around 35.

It was about 1:20 in the afternoon.

The man went to the front desk and asked for an interior room several floors up. He signed the register as Roland T. Owen, and gave Los Angeles as his home address. He paid for one day.

Owen had a cauliflower left ear, which made it easy for people to see him as a professional boxer or wrestler. He had dark brown hair and a large, horizontal scar in the side of his scalp, rising above his ear. This was at least partially covered by hair that he had combed over the disfigurement. The desk clerk gave Mr. Owen the key to room 1046 and sent bellboy Randolph Propst with him to the elevator, to show Owen the way to his room. Propst later described Owen as neatly dressed, wearing a black overcoat.

Propst and Owen chatted on the way up to the tenth floor. Owen told the bellboy that he had been at the Muehlebach Hotel the night before, but they had charged him the outrageous price of $5.00 for his room. (With inflation, $5.00 in 1935 had the buying power of a little over $80.00 in 2012 dollars.)

As the two got off the elevator on the tenth floor they turned right and headed down the corridor, turned left at the corner, then left again when the corridor reached the corner with the stairwell. Room 1046 was just down the hallway on their left, on the inner row of rooms looking down on the hotel’s court, rather than the outer row that looked down on 14th Street. Owen unlocked the door and entered while Propst turned on the light.

Owen walked through a short entryway—closet to his right, bathroom to his left—and saw the room itself. Beyond the entryway, it measured nine feet wide and 12 feet long. The bed was to his right and the small stand with the telephone to his left. Situated more or less along the middle of the left wall stood a writing table with chair, and beyond that, angled in the northwest corner, was the dresser. Angled in the northeast corner was an easy chair.

Propst watched as Owen took a black hair brush from his overcoat pocket, along with a black comb and toothpaste. That was it.

Owen placed the three items above the sink, and the two men then exited the room and were headed back down the hallway, toward the elevator, when Propst asked if it was okay with Owen if Propst went back to the room and locked it. Owen gave him the key, and Propst went back to the room, turned off the lights, and locked the door. He then returned to Owen, gave him the key, and the two of them took the elevator back to the first floor, where Propst went back to his duties and Owen left the building.

The maid that first day, Mary Soptic, had come back to work after a day off, and around noon went to room 1046 to clean, finding the door locked. She knocked, and Owen let her in, which surprised her a little, since a woman had been staying in the room before Soptic’s day off. Apologizing, she said she could call back later, but Owen said it was all right, and to go right ahead. Just moments later, Owen told her not to lock the door—that he was expecting a friend in a few minutes. Soptic noticed that the shades were tightly drawn (this was true every time she or any other member of the hotel’s staff entered), and that the lamp on the desk provided the only light, which was rather dim.

In her signed statement to the police, she said that, from his actions and the expression on his face, Owen seemed like “he was either worried about something or afraid,” and that “he always wanted to kinda keep in the dark.”

(Side Note: I do a fair amount of quoting from the signed statements made by witnesses to the police. Some years ago I first heard about this case I started checking the microfilm of the Kansas City Star, the Kansas City Times, and the Kansas City Journal-Post to the news accounts of the day. While I was doing that we received the monthly copy of The Informant, the in-house newsletter published by the Kansas City Police Department. That issue had an article about the Cold Case Squad. I wrote them a letter, sketching out this case, and asking if it was possible for me to look through the files of the case. The Cold Case Squad put me in touch with the Records Department, and I ordered a complete copy of the entire file. The entire file fills about a ream of paper.)

While Soptic continued cleaning, Owen put on his overcoat, went into the bathroom to brush his hair, and then left the room, reminding her to leave the door unlocked, because “he was expecting a friend in a few minutes.”

Mary Soptic didn’t see Owen again until about four o’clock, when she went back to 1046 with the fresh towels that had finally been delivered by the laundry. The door remained unlocked, the room was dark, and she could see from the light from the hallway that he was lying across the bed, completely dressed. Presumably from the light from the hall, she noticed a note on the desk.

“Don, I will be back in fifteen minutes. Wait.”

The next morning, Thursday, January 3, Soptic headed to 1046 around 10:30 to clean it. Assuming that Owen was out, she unlocked the door with her passkey (which she could only do if it had been locked from the outside) and entered.

Owen was sitting in the dark.

Soptic realized that someone else had locked the door from the outside.

The telephone rang.

Owen answered, and after a moment said, “No, Don, I don’t want to eat. I am not hungry. I just had breakfast.” After a moment he repeated, “No. I am not hungry.”

After cradling the phone, Owen asked the maid about her job. Did she have charge of the entire floor? Was the President a residential hotel? Then he looked around, and said that the Muehlebach Hotel had tried to hold him up on the price for an inside room just like 1046.

Soptic finished cleaning, gathered up the soiled towels, and left.

Around four o’clock that afternoon, after the clean towels had arrived from the laundry, she took a fresh set to Owen’s room. She heard two men talking, and knocked gently on the door.

A rough voice asked, “Who is it?”

The maid identified herself and said that she wanted to leave the clean towels.

“We don’t need any,” replied the rough voice loudly, which was peculiar since Soptic knew there were no towels in the room, having removed them herself that morning.

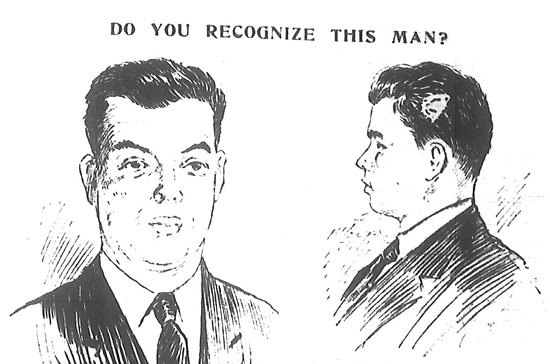

This police sketch of Roland T. Owen appeared in the Star.

That afternoon, Jean Owen (no relation to Roland T.), a 30-year-old woman who lived in Lee’s Summit, drove into Kansas City to do some shopping and then meet with her boyfriend, Joe Reinert, who worked at the Midland Flower Shop. After a few hours shopping, she started to feel ill and went to the flower shop and told Mr. Reinert that she didn’t feel up to going out that night, and that she would get a room at the Hotel President so she could avoid driving back to Lee’s Summit till the next day. She told Reinert that she would let him know what room she was staying in. She arrived at the Hotel President about six o’clock and registered a little over half an hour later.

Jean Owen called Reinert about ten to seven and told him that she was staying in room 1048. He came to the hotel about two and a half hours later, and they visited for another two hours, when he left.

In her statement to the police, she said that during the night she

heard a lot of noise which sounded like it (was) on the same floor, and consisted largely of men and women talking loudly and cursing. When the noise continued I was about to call the desk clerk but decided not to.

Charles Blocher was the elevator operator for the graveyard shift at the hotel, and he started work a little before midnight on January 3. For the first hour and a half of his shift he was pretty busy, but around half past one business tapered off, though there seemed to be a fairly boisterous party in room 1055. As he puts it in his statement, sometime in the first three hours

I took a woman that I recognized as being a woman who frequents the hotel with different men in different rooms. It is my impression from this woman’s actions that she is a commercial woman. I took her to the 10th floor and she made inquiries for room 1026 (sic) – about 5 minutes after this I received a signal to come back to the 10th floor. Upon arriving there I met this same woman and she wondered why he wasn’t in his room because he had called her and had always been very prompt in his appointments and she wondered if the might be in 1024 because the light was on in there the transom was opened – she remained about 30 or 40 minutes then I received a signal to go back to the 10th floor – I went back and this same woman appeared there and came down on the elevator with me and left the elevator at the lobby. About an hour later she returned in company with a man and I took them to the 9th floor – I later received a signal to go to the 9th floor at about 4:15 AM and this same woman came down from the 9th floor and left the hotel. In a period of about 15 minutes later this man came down the elevator from the 9th floor complaining that he couldn’t sleep and was going out for a while.

The woman’s searching for 1026 rather than 1046 raises some interesting questions. Was she actually there to see Owen, or was it another man altogether? Did she get the room number wrong, or did Owen inadvertently give her the wrong number? Did this woman have anything to do with what happened in 1046 that night? (The use of 1026 as Owen’s room number appears to have gone out over the wire service account of the story, as that is what appears in the accounts I have seen in papers from the south and the northeast parts of the country.)

Blocher described the man as being about five foot six, slender, about 135 pounds, wearing a light brown overcoat, brown hat, and brown shoes. The woman was about five foot six, with black hair, weighing about 135 pounds, wearing a “coat of black hudson seal or imitation hudson seal.” The coat had a collar with a light fur strip, and the collar stood up.

The woman was also noted by James Hadden, hotel’s night clerk, when she left the building. He recognized her as someone he had seen “in and out of the hotel at various times and at various hours of the night and early mornings.”

The next known encounter between Owen and the hotel staff took place Friday, just a little after seven o’clock, when Della Ferguson, the telephone operator, took over the board. She noticed that the board indicated that the phone for 1046 was off the hook. At ten after, when the phone was still off the hook, with no one using it, she requested that bell service send a bellboy up to the room to tell the occupant to hang up the phone.

The bellboy was Randolph Propst, who had taken Owen up to the room when he had first checked in. When he got to Room 1046 the door was locked, and a “Don’t Disturb” sign was hanging from the knob. Propst knocked loudly and got no response. After a moment he again knocked loudly and finally heard a deep voice say, “Come in.” He tried the doorknob and, yes, it was locked. Again he knocked, and this time heard the deep voice tell him to “Turn on the lights.” He knocked yet again, and again, and finally, after seven or eight times, yelled through the door, “Put the phone back on the hook!” He got no response and returned to the lobby, where he told Della Ferguson that the guy in the room was probably drunk, and that she should wait about an hour and send somebody else up them.

About half past eight, Della Ferguson noted that the phone for 1046 was still off the hook, and she sent bellboy Harold Pike up to ask Owen to replace the receiver. When Pike got there, he found that the door was still locked, and he used a passkey to let himself in—again indicating that the door had been locked from the outside. With the light from the hallway, Pike noted that Owen was lying on the bed naked, surrounded by what appeared to be dark shadows in the bedclothes, apparently drunk. He also saw that the telephone stand had been knocked over, and that the phone was on the floor. Pike straightened the stand and put the phone on it, securing the receiver in its place.

He locked the door behind him and returned to the lobby, telling his supervisor that Owen was lying naked on the bed, apparently drunk.

Around 10:30 to 10:45 that morning another operator reported to Betty Cole, the head operator, that the phone for 1046 was again off the hook. Around 11 o’clock Randolph Propst headed back up to the room, noting that the “Don’t Disturb” sign was still on the door. After knocking loudly three times with no response, he unlocked the door with his passkey and entered.

“[W]hen I entered the room this man was within two feet of the door on his knees and elbows – holding his head in his hands – I noticed blood on his head – I then turned the light on – placed the telephone receiver on the hook – I looked around and saw blood on the walls on the bed and in the bath room …”