One of the wind’s main targets as it heaved the fiery embers away from Convention Hall was the Second Presbyterian Church that occupied the land across the street. The first small flame was seen in the steeple, and then many of the flying brands landed on the roof of the church and on the pastor’s home. (One man was seen standing on the roof of a house that stood close by the church, spraying his house with water, just barely staying ahead of the fire.) As if the burning of the Convention Hall and Lathrop School had only whetted the fire’s appetite, it attacked the church and the manse with renewed anger and ferocity. Rev. Jenkins was on business elsewhere when the fire hit, but his wife and daughter were at home, only just able to flee the surrounding flames, leaving everything of worth in the house, except for themselves and the clothes they were wearing. Dr. Jenkins’ personal library by itself was valued at $10,000 in 1900 dollars. Inflation says it would be worth at least 29 times that amount 112 years later—and, of course, many of the books would have appreciated far beyond mere inflation.

The collapse of the Second Presbyterian Church followed shortly.

The church had a majestic steeple placed in the corner, next to the main entrance to the building. The steeple was the site where the windblown fire first attacked, putting the flames outside the range of the water from the fire hoses.

The reports, though, describe the steeple’s falling differently from that of the Hall’s roof, which had been so powerfully loud. The steeple’s collapse seemed profoundly slow and silent. Making nearly no noise, the steeple began to fall slowly in on itself, the point dropping with a slow, earnest majesty, collapsing through the hole caused by its own weight, into the growing shell of the church itself.

It made almost no noise until that final moment when it crashed into the floor, spewing still more sparks and burning cinders roiling out through the swirling smoke.

The crumbling of the spired tower initiated the imploding of the church’s roof, the crushing noise of which more than compensated for the quiet grandeur of the fallen steeple.

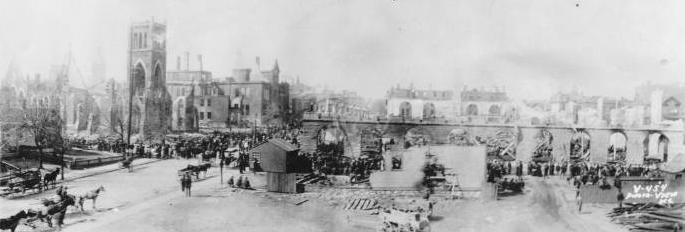

The hall, the school, the church, and the manse (none of them insured for their worth) were not the only buildings destroyed by the spreading fire.

With the fire spreading so quickly, many other residences and businesses were in danger of being destroyed, and the fire department started evacuating them. The entire 200 block of 12th Street, mostly boarding houses, was evacuated, the tenants hauling what they could of their belongings out into the street. The Williamson block met with almost total devastation.

Under the direction of the chief of the fire insurance patrol, the Fire Department used over 400 tarpaulins to shield the rescued belongings that evacuees had brought outside.

The fire's aftermath

Mr. Roby, mentioned earlier as being misidentified as the stranded man on the roof, did discover a problem that plagued the fire department as they fought to contain the fire—not enough water. As noted in the Kansas City Star in its edition the evening of the fire, “The water pressure was inadequate to cope with the flames, although every hydrant and piece of apparatus was at work.” (It seems odd that no one reasoned that this may have been the cause of the low water pressure.)

While the fire fighters were still struggling mightily to halt the spread of the fire and bring it under control, questions were already being raised about the possibility of rebuilding the Convention Hall. E.M. Clendenning was the secretary of the Commercial Club. As he moved through the crowd at the fire, heading toward a meeting with such Kansas City business luminaries as U.S. Epperson, D.P. Thompson, John W. Speas, and Walter P. Dickey, many people recognized him, and started pledging money toward the rebuilding of the Convention Hall.

The meeting was to determine whether rebuilding for the convention was a possibility.

There was at least one person in Kansas City who maintained that it was not a possibility. In the same issue of the Star as the observation about the low water pressure noted above, an unnamed architect, “acquainted with the details of the Convention hall and who saw the fire,” said,

It is absolutely ridiculous to talk about rebuilding the hall in time for the convention of July 4. It might be rebuilt in a way by duplicating the building. But this fire has taught us the lesson that we must not rebuild it as it was before. There was too much woodwork in the building, too many beams and different layers of pine flooring. It was a perfect tinder box. It really is a blessing that it burned, because, built as it was, it was bound to burn some time, and just think what would have happened if it had caught fire while it was filled with people. ... Now we should not build another fire trap just because we have national convention here in July. We can make room for the Convention some other way, but our Convention hall ought to be so built that it would be practically fireproof. That could not be done in three months.

So, this architect was right about everything—except whether it was possible.

The members of the Convention Hall Association met and sent a telegram to C.A. Walsh, Secretary for the Democratic Convention, saying Kansas City still wanted to host the convention. Walsh’s reply must have been exactly what they were hoping to hear—

Any person who has come in contact with business men of Kansas City must have been impressed with the fact that the town contains a higher degree of public spirit than any other city in the United States. I believe its people will provide a suitable place for the Democratic National Convention.

Those at the meeting discussed the building of George Warder’s Grand Opera House, which had been built 13 years earlier at Holmes and Grand. The Opera House had opened just 100 days after ground had been broken.

Homer Reed, who was present and spoke for the Democratic executive committee, wanted a contractor’s bond to assure that the new Convention Hall would be completed in time for the Democratic gathering.

Also at the meeting was A.G. Southerland, who was the general Western agent for the Carnegie Steel Company of Pennsylvania. Southerland also managed Kansas City Wire and Iron, as well as a foundry in Riverside. Southerland asked for the contract for rebuilding the Hall, promising that the Convention Hall’s steel needs would always be at the front of the line for Carnegie’s Pittsburgh factory. Late that night Southerland made a long distance call (quite a rarity in 1900) to Charles M. Schwab, Carnegie president, and reported to the committee that the proposal would be put to the Carnegie board the next morning.

Calculations determined that, by themselves, the eight girders that would support the weight of the new hall would require 1000 tons of steel. The eight girders would each be 188 feet long, and the cost of just those girders would be $50,000. The committee expected that the 1000 tons of steel salvaged from the ruins would be worth about $8000. The Kansas City Journal reported that “it is the purpose of the of the hall directors to erect an absolutely fireproof building on the old site, taking advantage of the splendid foundations that have remained almost uninjured by the fire.”

So, they set to work. The Kansas City spirit kicked into high gear. The board called for a mass meeting at 8:00 on the night of April 5 to raise the money needed beyond the insurance coverage, and instructed Loomas to start the clearing of the debris from the site the morning of the 5th, a Thursday.

That morning, Frederick Hill agreed to design the fireproof new building, waiving any claims for back pay, setting his fee at 2.5% of the cost of the rebuilding, not to exceed $5000. Apparently Hill was little short of brilliant in the rebuilding, redesigning much of the building, while anticipating many of the problems that arose, reworking the plans with skill and imagination.

Beyond the corporate subscriptions, private individuals began subscribing to support the rebuilding, from $5.00 to $500 to $1000. Composer and conductor Carl Busch said that the concert already scheduled at the Coates Opera House on April 19 would be turned into a benefit for the new hall.

The town of Frankfort, Kansas, which had survived a tornado three years before, and had been aided in their rebuilding by a donation by the Commercial Club, now donated a like amount to the rebuilding of Kansas City’s Convention Hall.

When July 4 finally came, so did the Democrats.

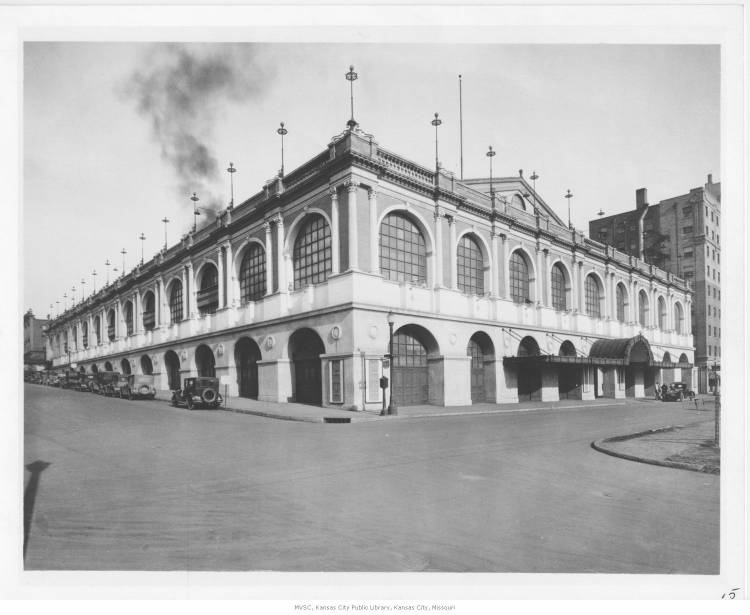

The New Convention Hall

The new, fireproof building was not completely completed—that would take to the end of the year—but it was able to host a national convention. The Democrats met in Kansas City and nominated William Jennings Bryan as their candidate for president.

That fall Bryan lost the election for the second of three times.

The experience took its toll on Rev. Jenkins. The First Presbyterian Church invited the Second Presbyterian Church to use their facilities until the homeless congregation could find a new building, but this act of good will was not enough to keep him going. The fragile health of his wife and the trauma she faced undoubtedly contributed to his decision, but it must have been devastating to him as well—not only because of the loss of his library and virtually all of his possessions. He also had to face the idea that, after working so hard for five years to rebuild the congregation he had inherited back into a strong, vital community, he would have to start over. By the end of 1900 Rev. Jenkins stepped down as pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church, and moved to Chicago, where he eventually focused on his writing.

During August of 1900, Fire Chief Hale took a contingent of Kansas City’s fire fighters to France for the Grand Paris Fire Congress and Exposition, going from there “to visit several of the largest cities in England, Ireland and Scotland.” They did demonstrations. Chief Hale was world famous for his invention of fire fighting machines like the Hale Water Tower and the Hale Swinging Harness.

However, Hale and Kansas City’s newly elected mayor, future Senator James A. Reed, did not get along, and in 1902 the mayor persuaded a majority of the city council to join him in firing Hale—on charges that had no specific acts attached, against which he was not allowed to defend himself before the council. He was replaced as chief by first assistant chief, Edward Trickett.

Hale continued to be involved with fire fighting as an inventor and manufacturer until he died in 1923.

John Loomas was in his mid-forties when the fire took place. He had labored

with untiring energy to direct the work of the rebuilding. He was scarcely ever away from the building save during his sleeping hours, his time being spent in spurring the men on in great efforts. He often led the way into dangerous places, where the workingmen feared to go.

He continued as manager of the Conference Hall and the Priests of Pallas until his death on May 17, 1901. He had just been re-elected to the position three days before dying.

“The big halls, when they take fire, burn like hayricks.”

— Chief George C. Hale

Resources

Books

Corrie, Frank G., The First One Hundred Years: Second Presbyterian Church [Centennial, 1865-1965]. Kansas City, Mo., [1965]. MVSC 285 C82F

Hale, George C., History of the World’s Greatest Fires. Kansas City, Mo., Press of F. Hudson Publishing Co. [c. 1905] MVSC 614.84 H16

Hale, George C., Souvenir of Kansas City and Her Fire Department to the Grand Paris Fire Congress and Exposition, Paris, August 13, 1900. Kansas City,Mo., Hailman-Reily Printing Co. [1900]. MVSC Q 099 H16S 1900

Hill, John B., Second Church Reminiscences: an address on the history of the Second Presbyterian Church, Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City, Mo. [1944]. MVSC Q 096.1 H64S

The Kings and Queens of the Range., Kansas City, Mo., The Kings and Queens of the Range. [Periodical] MVSC F 338.17 K55, v. 3, no. 27

White, Edwin H., Rebuilding Convention Hall: an episode in the life of a city. Kansas City, Mo. [1963]. MVSC Q 977.8411 W58R [Manuscript]

Newspapers

Kansas City Journal, April 1900

Kansas City Star, April 1900

Kansas City Times, April 1900

MVSC Newspaper Clippings Files