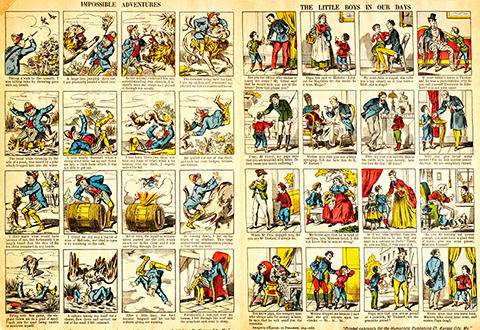

It’s easy to say that reading for entertainment has taken a backseat to television and video games in today’s visually driven culture. A popular form of amusement, however, still has the power to capture the imagination of both younger and mature readers — comics. With Planet Comicon attendees taking over downtown this weekend, it seemed like a good time to highlight some of the comics available to researchers in our Missouri Valley Special Collections at the Central Library.

Local History Blog

In 1920s Kansas City, hotel ballrooms, restaurants, and nightclubs teemed with crowds excited to hear the region’s signature jazz sound and eager to take advantage of the city’s lax alcohol prohibition enforcement. By visiting “Paris of the Plains,” as the city was nicknamed, one could enjoy performances of everything from vaudeville to Shakespeare, or even one of the newly invented motion pictures. For Black Kansas Citians, however, some of whom had served their country in WWI and visited the real Paris in France, much of their hometown was closed off to them. The Beau Brummel Club stepped in to help improve the social and civic lives of Black veterans and civilians. A reader asked What’s Your KCQ? to investigate the club’s history.

When the Sporting Kansas City soccer club released new state line-themed jerseys in February 2022, fans noticed that one of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s shuttlecock sculptures, along with the Rosedale Memorial Arch, appeared together on the back. A curious reader asked What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to investigate the history of the arch, and why Sporting chose it to represent Kansas City, Kansas, on the jersey. In the aftermath of World War I, victorious American troops returned from Europe and patriotism was running high. In 1920, Kansas passed a law allowing public funds to support the construction and installation of military monuments, and the citizens of Rosedale, Kansas, were eager to take advantage of the legislation. And they knew just the spot.

National Immigrants Day on October 28 celebrates the U.S. as a melting pot of diverse cultures, customs, and ethnicities and honors the perseverance and contributions of those who sought opportunity in America. Among them was Nikoles Aleshi, a poor Italian immigrant who built a successful grocery business in Kansas City at the turn of the 20th century. But he had grander aspirations of creating a new national language that would be easier for non-English speakers to learn. His story fascinated a local reader who asked What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to investigate it further.

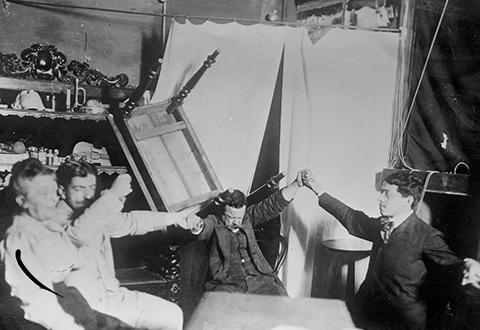

A reader helped us get into the Halloween spirt by asking, “Did Spiritualism ever become popular in Kansas City?” The What’s Your KCQ? team found that not only did the movement gain followers here, it also caused a scandal that made national news. In 1881, Col. Robert Van Horn published an article, Philosophy: The New Hypothesis, in The Kansas City Review of Science and Industry. Van Horn, a publisher, congressman, and former mayor of Kansas City, had a distinguished record of service as a Union officer during the Civil War. He had also experienced personal tragedy beyond the horrors of war: He and his wife had four sons, only one of whom would outlive him. Van Horn was curious about life after death, but science was not answering his questions. In his article, he wrote that humankind needed to find life not in “animal and vegetable alone,” encouraging his readers to seek answers beyond our scientific understanding.

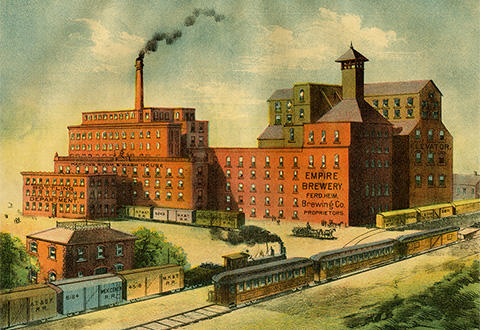

Among the available libations at the J. Rieger & Co. distillery in Kansas City’s East Bottoms is a specially brewed lager, Heim Bier – a homage to a pre-Prohibition family brewery that once operated and thrived on the site. A What’s Your KCQ reader recently enjoyed a pour and inquired about the name.

What’s the Heim history? It traces to Austria, where Ferdinand Heim Sr. was born in 1830. He and his brother Michael were trained by their father as ropemakers, emigrated to the United States when Ferd was 21, and tried their hands at a number of ventures before purchasing a small brewery in Manchester, Missouri, near St. Louis. They were part of a massive influx of German immigrants who settled in Missouri in the 19th century, drawn to the fertile land along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. Producing German lager proved to be a viable business. The Heims found their way to East St. Louis, Illinois, where they opened the Heim & Brother Brewery (later named the Heim Brewing Company). Michael passed away at an early age in 1883, and Ferd’s eldest son Joseph stepped into his uncle’s role.

Kansas City culture wouldn’t be the same without fall fairs and festivals. But what’s celebrated and by whom has changed a great deal throughout the city’s history. An alarmed reader recently wrote to What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star after running across a souvenir from an 1895 parade in the city on eBay. The antique was a remnant of the Priests of Pallas (POP) parade and included the letters KKK. The KCQ team quickly assured our reader that the letters did not represent that KKK, but something else entirely.

Kansas City in the 1880s was struggling to shed its frontier image, and the city was filled with a sense of boosterism. Professional and social clubs formed, their members all hoping to make a name for the young city and attract new investments. One such organization, the Flambeau Club, began holding parades to attract attention to downtown businesses. Later, inspired by Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans and the Veiled Prophet parade and ball in St. Louis, the Flambeaus decided Kansas City needed its own carnival season. In September 1886, a parade association formed to plan a multi-day festival the following year.

In a recent article about the history of Municipal Stadium, we learned that the former home of the Kansas City Athletics and first home of the Royals and the Chiefs was originally called Muehlebach Field. We also learned that it was named after Blues owner, George Muehlebach Jr. A reader noticed the same name on a downtown hotel sign and asked What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to explain who the Muehlebachs were.

The family patriarch, George Muehlebach Sr., was born in Aargau, Switzerland, in 1833 and emigrated to the U.S. in 1854. Starting out in Lafayette, Indiana, he and three brothers — John, Peter, and Francis X. — eventually found their way to the bustling town of Westport, Missouri.

Just east of the Country Club Plaza and north of Brush Creek is an urban oasis of park land, gardens, and trails, including an eight-acre nature reserve and lake showcasing native plants and habitat. Opened in 2000, the Kauffman Memorial Garden and Legacy Park honor the philanthropic spirit of Ewing and Muriel Kauffman. The property, which includes the Kauffman Foundation headquarters and Anita B. Gorman Conservation Discovery Center, offers public greenspace in the heart of the city. But it is the neighborhood that existed before the Kauffman campus that is the subject of the latest installment of What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library. Jared Pessetto was studying maps of the area from the 1980s, which showed a sizable residential district around 48th Street and Rockhill Road. He asked KCQ: “What happened to the neighborhood where Kauffman Memorial Garden is now located?”

The answer involves streetcar transit, flooding, university expansion, and, ultimately, urban conservation.

A body in the old Waldo water tower? The first hospital for Black patients west of the Mississippi River? Before the Chiefs … the Blues? What’s Your KCQ?, on which the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star collaborate to answer reader-submitted questions about local history, quirks, and curiosities, tackles a trio of recent inquiries: As a kid, I remember hearing a body was once found inside the Waldo water tower. Did that really happen? What's the history of Douglass Hospital in KCK? I heard Kansas City had a pro football team that played at Muehlebach Field before the Chiefs. Is that true?