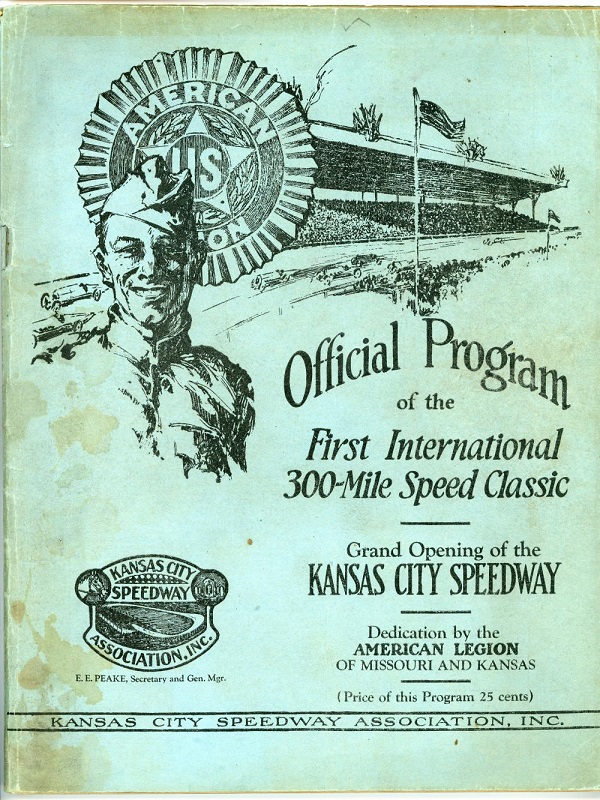

On September 17, 1922, professional racecar drivers vied for a $30,000 prize in the inaugural race at the Kansas City Speedway. Advertisements declared that the winner would exhibit the "greatest display of skill, nerve, and daring in the history of modern sport." Although the track would soon become an obscure footnote in Kansas City's history, its design was perhaps the best in the nation when it opened to a roaring crowd of 50,000 spectators.

In the "golden age" of automobile racing in the 1920s, the best tracks designed for top-end speed were made of wood. The Kansas City Speedway Association accordingly constructed its speedway out of a million feet of lumber 2 x 4's, set on end and bolted together to form a 1 1/4 mile oval track. In contrast to traditional materials (primarily brick or dirt), the board tracks of the era allowed for very steep 45-degree banks around the curves to help the cars maintain faster speeds.

Kansas City's board track was located at 95th and Troost, where Pratt & Whitney later built a WWII-era aircraft engine plant. Two steel and concrete grandstands faced one another, giving the track a combined 50,000-seat capacity. Parking lots and the infield could accommodate 20,000 cars. State of the art technology included an electric timing device that helped track the cars' progress. There were only about 20 board tracks in the nation, and several fans and drivers declared Kansas City's to be the best of them all.

Many nationally-famous drivers entered to compete in the first race, originally scheduled for September 16, 1922. Among them was Cliff Durant, head of the Durant Motors Corporation, who was positive that world speed records would be set in Kansas City. To make the event even more sensational, Durant chose to come to Kansas City by flying in a private plane from Oakland, California. Spectators who gathered at a nearby airfield to greet him were disappointed to learn that the plane had crash-landed near Leavenworth, Kansas. Fortunately, no one was injured in the crash, and Durant was still able to enter the race.

Most of the other drivers and their cars arrived by more traditional means: trains. Starting on September 1, the six- and eight-cylinder cars sat on display at Union Station for several days, raising hype for the upcoming contest. Organizers set the race at 300 miles in distance - 50 miles more than any other board track race in history. They expected the winner to finish in less than three hours.

The race was postponed one day due to rain, but on September 17, 1922, all of the preparations came to fruition. Driver Tommy Milton won the race at an incredible average speed of 107 mph; nearly 13 mph faster than the winner of that year's Indianapolis 500; which took place at a brick track. One accident occurred, claiming the life of Roscoe Sarles, a driver and movie star from California. But such tragedies were not unexpected in 1920s racing, and it ultimately could not spoil the merriment.

Unfortunately, Kansas City's board track disappeared as quickly as it had stormed the professional racing scene. Its investors were a group of local businessmen who had hoped to make great profits, but it proved difficult to recoup their $500,000 construction investment. Only four races were held between 1922 and 1924, with the last drawing just 20,000 spectators. Instead of blossoming into one of the nations' premier racing cities, as the builders had anticipated, Kansas City lost the sport entirely.

In just two years, the board track (made from untreated lumber) had rotted to such an extent that cars could no longer safely race on it. The last race actually had to be cancelled when large holes appeared after the race leaders had already driven 150 miles. Without any finances available to replace the surface, the Kansas City Speedway closed permanently in 1924. Today there are no visible remains of the "old board track," but since 1999 Kansas City's racing enthusiasts have enjoyed NASCAR races at the Kansas Speedway in Kansas City, Kansas.

View images of local racing venues that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Bendix Plant; site of the Kansas City Speedway at 95th and Troost

- Old Elm Ridge Race Track; 1916, designed for horse racing, it occasionally hosted car races

- Old Elm Ridge Race Track, car

- Old Elm Ridge Race Track, open-air car

- Postcard of Elm Ridge Race Track and Clubhouse

Check out the following books and articles about the Kansas City Speedway, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- "Do You Remember the Kansas City Speedway?," in the Kansas City Star, April 9, 1973.

- "K.C.'s Wooden Race Track Passed into Oblivion 61 Years Ago," in the Kansas City Star, July 3, 1985.

- The Golden Age of the American Racing Car, by Griffith Borgeson.

- Saturday Matinee in Olde KC, by Chris Wilborn; pp. 23-24.

Continue researching the Kansas City Speedway using archival material held by the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- "Auto Speedway Built under Difficulties," Popular Mechanics, November 1922.

- "Autoparade to Open Speedway September 16," Kansas City Journal-Post, August 29, 1922.

- Kansas City... The Way We Were; contains two photographs of the Kansas City Speedway.

- "Kansas City Speedway Racing - The Greatest Thrill of All!," Kansas City Star, July 30, 1922; full-page newspaper advertisement.

- "Speedway Races July 22," Independent-Kansas City, July 15, 1916.

- "The Main Steel Grandstand at the Speedway Nears Completion," Kansas City Star, August 13, 1922.

References:

Chris Wilborn, Saturday Matinee in Olde KC (Kansas City, MO: Wilborn & Associates, 1999), 23-24.

Kansas City Speedway Association, inc., advertisement, "Kansas City Speedway Racing - The Greatest Thrill of All!," Kansas City Star (July 30, 1922).

"The Main Steel Grandstand at the Speedway Nears Completion," Kansas City Star (August 13, 1922).

James P. McGilley, "Do You Remember the Kansas City Speedway?," Kansas City Star (April 9, 1973).

Tom Hutchinson, "K.C.'s Wooden Race Track Passed into Oblivion 61 Years Ago," Kansas City Star (July 3, 1985).