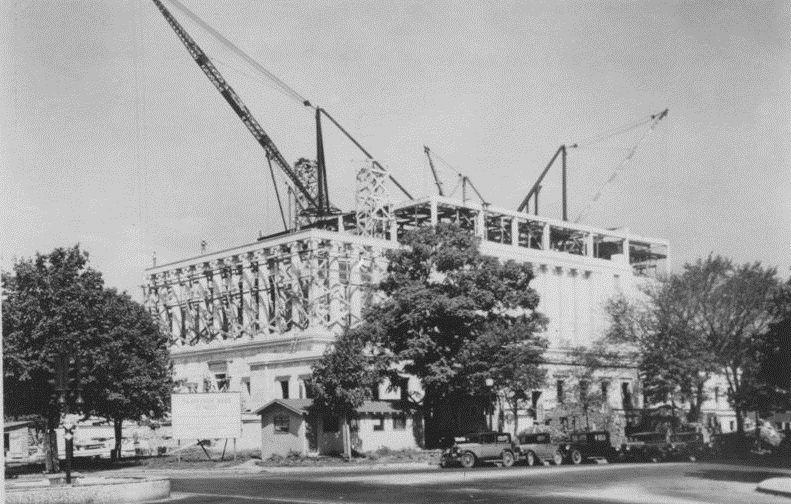

On June 9, 1933, the Jackson County Court awarded a $2,073,609 contract to the Swenson Construction Company for construction of the Jackson County Courthouse. The opulent Art Deco-style 300-foot tall building would reside alongside Kansas City's skyscrapers and provide much-needed space for the court system. Equally important, its construction along with dozens of other projects completed as a part of Kansas City’s “Ten Year Plan” would provide jobs to hundreds of beleaguered Kansas City residents then suffering from the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression.

The Ten Year Plan was the creation of political "boss" Tom Pendergast, city manager Henry Francis (H.F.) McElroy, and Conrad Mann, president of the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce. Necessitating a $50 million bond that passed in 1931, its main goal was to improve public facilities and infrastructure that were inadequate to the growing city's needs. The project improved Kansas City's traffic ways, sewer system, water works, parks, postal services, police and fire fighting equipment, street signs, and pedestrian walkways. Brush Creek was paved to (theoretically) prevent flooding. The largest new landmarks included Municipal Auditorium, City Hall, Police Headquarters, and the Jackson County Courthouse.

In several respects, the Ten Year Plan was only possible because of the Great Depression. While most large U.S. cities provided soup lines for their unemployed and hungry citizens, Kansas City’s charter forbade the use of taxes for such direct relief efforts. Nonetheless, McElroy, Mann, and Pendergast believed the Ten Year Plan would provide relief by hiring currently unemployed residents to improve the city’s infrastructure. Relative to other cities of its size, Kansas City had lower unemployment rates and fewer business closures during the depression. The famous journalist William Allen White praised this success, saying that Kansas City “does not depend on soup kitchens maintained by charity to feed her unemployed while they are idle. Instead, she voted bonds so that they may be given jobs at useful and beautiful public improvements.” After the inauguration of President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, the federal government even implemented similar programs nationally with the Public Works Administration (WPA).

Whenever possible, the foremen in charge of Ten Year Plan projects abstained from using tractors or other heavy machinery so that each project could employ more manual labor. This worked to great effect, as between 15 and 22 thousand workers found employment from the projects. Perhaps no one benefited as much as boss Tom Pendergast, though. His Ready-Mixed Concrete Company provided most of the concrete at a great profit. Pendergast's sway over the Missouri Democratic Party and the early success of the Ten Year Plan also led President Roosevelt to place him in charge of all federally-funded public works programs in the state of Missouri. Not surprisingly, WPA funding provided a substantial share of the costs for post-1933 projects in Kansas City, including the Jackson County Courthouse that was approved in June, 1933.

The new courthouse, completed on December 27, 1934, replaced a courthouse building constructed in 1892 that was small and considered unsafe by 1930s-era fire codes. By contrast, the new building contained offices for county assessors and other administrators, two-story tall court rooms, the county jail, and an execution chamber. Paintings, plaques, and statues adorned a grand entryway whose walls were lined with marble. Space equivalent to two of its 14 floors was left vacant to allow room for future expansion. The building even boasted air conditioning, a rare feature at the time. Its grandiose and forward-looking design has ensured the building's longevity. It still serves as Jackson County's courthouse today.

Read full biographical sketches or profiles of people and places associated with the Ten Year Plan; prepared for the Missouri Valley Special Collections, the Kansas City Public Library:

- Jackson County Courthouse Profile, by Susan Jezak Ford; constructed as a part of the Ten Year Plan.

- Biography of Thomas Pendergast (1873-1945), business owner and "political boss," by Susan Jezak Ford.

- Biography of Henry Francis McElroy (1865-1939), City Manager, by Nancy J. Hulston; McElroy and Tom Pendergast came up with the idea for the Ten Year Plan.

- Biography of Conrad Mann (1871-1943), civic leader, by Janice Lee; Mann was chairman of the Civic Improvement Committee of One Thousand, which developed the idea into a workable plan.

- Biography of Harry S. Truman (1884-1972), President of the United States (1945-1953), by Susan Jezak Ford; Truman, then a Jackson County Judge, helped promote the Ten Year Plan to the public.

- City Hall Profile, by Ann McFerrin; constructed as a part of the Ten Year Plan.

- Municipal Auditorium Profile, by Susan Jezak Ford; constructed as a part of the Ten Year Plan.

View images of people and places associated with the Ten Year Plan that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Tom Pendergast.

- H.F. McElroy.

- Conrad Mann.

- Conrad Mann at Municipal Airport.

- Lou Holland and Conrad Mann at Municipal Airport Dedication.

- Conrad Mann, autographed photograph.

- Harry S. Truman.

- City Hall; constructed as a part of the Ten Year Plan.

- City Hall and Jackson County Courthouse; both constructed as a part of the Ten Year Plan.

- Brush Creek; paved as a part of the Ten Year Plan.

Check out the following books and articles about the Ten Year Plan held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- "Boss Tom's Legacy," by Sherwood Goodenough, in Greater Kansas City Magazine, 2002; examines how boss Tom Pendergast influenced Kansas City's development.

- Tom's Town: Kansas City and the Pendergast Legend, by William M. Reddig.

- Pendergast!, by Lawrence Harold Larsen.

Continue researching the Ten Year Plan using archival material held by the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Vertical File: Municipal Auditorium

- Vertical File: Pendergast, Thomas J.

- Vertical File: Clean-Up Campaign; organized in the 1930s to try to remove Tom Pendergast from power

References:

The Chamber of Commerce of Kansas City, Missouri, Where These Rocky Bluffs Meet: Including the Story of the Kansas City Ten-Year Plan (Kansas City, MO: Smith-Grieves Company, 1938), 173-174, 177-189, 191, 197-237.

A. Theodore Brown, Lyle W. Dorsett, K.C.: A History of Kansas City, Missouri (Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing, 1978), 196-202, 200, 205, 214, 226, 237, 241-242, 265.

Susan Jezak Ford, Jackson County Courthouse Profile, Missouri Valley Special Collections.

Henry C. Haskell, Jr., and Richard B. Fowler, City of the Future: A Narrative History of Kansas City, 1850-1950 (Kansas City, MO: Frank Glenn Publishing, 1950), 139-140.