On April 14, 1910, the City Council approved the creation of the Board of Public Welfare to provide aid to the city’s poor. As the brainchild of Kansas City philanthropist William Volker, the Board of Public Welfare was the first modern welfare department in the United States and a groundbreaking forerunner to modern welfare programs. The board was just one of Volker’s many memorable contributions that included the creation of Research Hospital, the establishment of the University of Kansas City (now UMKC), the purchase of the land for Liberty Memorial, and thousands of individuals who received some of his money when in need.

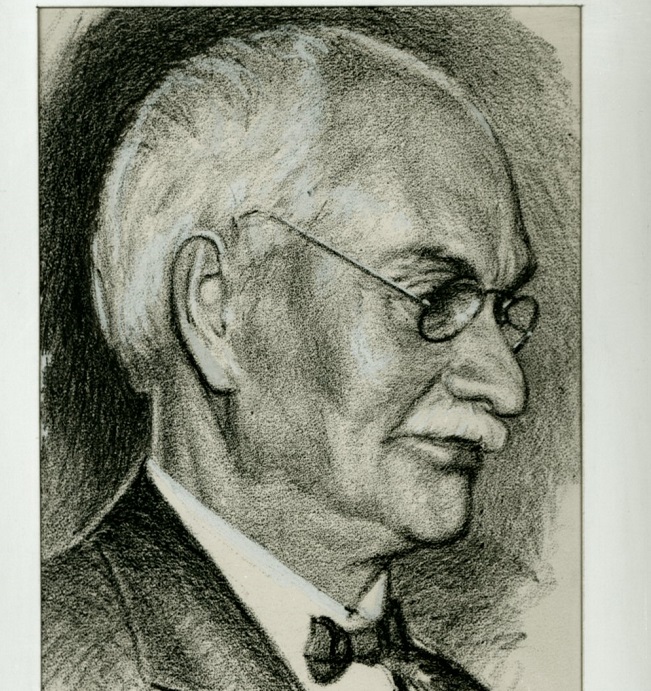

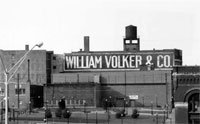

William Volker, an extremely successful businessman, was known to many Kansas City residents as “Mr. Anonymous” because of his penchant for discretely giving away large sums of money. Volker was born in Germany in 1859 and immigrated to the United States with his family in 1871. In 1882, with little money in his pocket, he moved from Chicago to Kansas City in hopes of opening a picture frame business. From this inauspicious beginning, William Volker and Company developed into a thriving home furnishings business that included satellite locations across the nation.

In 1908, Volker utilized the municipal government for philanthropy. He became the president of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, which oversaw the process of releasing prisoners. According to Herbert C. Cornuelle, Volker’s biographer, this board functioned as something of an employment agency with the unofficial slogan of “no job, no parole.” Volker believed that former prisoners were less likely to steal or commit other crimes if they were employed. Consequently, the board devoted its resources to the difficult task of finding jobs for prisoners.

Volker shortly found a second political outlet for his philanthropic desires. In 1909 high unemployment levels caused hundreds of jobless men to march on city hall in demand of work. In response, Volker proposed the novel idea of a department whose sole purpose was to fight poverty and squalor.

The resulting Board of Public Welfare sought to eliminate poverty by researching its causes, educating the public about those causes, training social workers, providing free legal services to citizens in trouble, loaning money to the poor, and even inspecting local businesses for safety and moral “decency” standards.

Despite authorizing the board in the first place, the City Council failed to fund it adequately. To fulfill the board’s budget needs, Volker anonymously donated $50,000 to get the board started and thereafter provided money whenever funds fell short.

Surprisingly, Volker received little praise for his efforts on behalf of the Board of Public Welfare. Some Kansas City residents lacked sympathy for a municipal department that, as they saw it, gave tax-funded handouts to the undeserving poor. Other critics ascribed to false rumors that Volker had created the board to fulfill his business’s labor demands with poorly-paid criminals.

Unfortunately, the Board of Public Welfare fell victim to political interference shortly after its creation. City politicians gradually gained control of the board and allocated its benefits to win political patronage rather than for the purpose of eliminating poverty. By 1918, Volker lost his last influence on the board and had grown skeptical of the concept of using politics for charity. He turned back to quietly providing private charity to individuals in need, whether they were strangers or friends. Eventually he provided financial assistance for civic projects such as the construction of Liberty Memorial and Research Hospital. He also started the William Volker Fund, which provided grants for scholarly research projects into libertarianism between 1935 and 1965.

Despite Volker’s ultimate pessimism about government involvement in public life, the Board of Public Welfare drew much attention both nationally and internationally while it thrived in the early 1910s. Municipal governments around the world began to copy some of its programs in an effort to reduce the prevalence and effects of poverty. Kansas City itself rejuvenated the department in 1940. Accordingly, William Volker deserves a prominent place in history as an innovator of public welfare in Kansas City and the nation.

Read biographical sketches of people associated with William Volker and the Board of Public Welfare, prepared for the Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library:

- Biography of William Volker (1859-1947), businessman and philanthropist, by Daniel Coleman

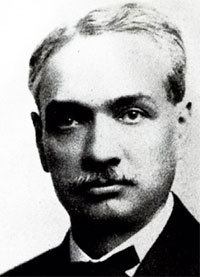

- Biography of Jacob Billikopf (1883-1950), social worker and philanthropist, by Daniel Coleman

- Biography of Edwin T. Brigham (1874-1950), social activist, by Jeremy Drouin; Brigham assisted Volker in finding employment for released prisoners

- Liberty Memorial Profile, by Ann McFerrin; Volker played a key role in acquiring the land for Liberty Memorial’s construction

View images that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections.

- Rose Volker, wife of William Volker

- William Volker Memorial Fountain

- William Volker Building Sign, 1991

- German Hospital, a beneficiary of William Volker’s philanthropy

- Helping Hand Institute, a private charity associated with the Board of Public Welfare

- Roselawn, home of the Volker family

Check out the following books and articles about William Volker and the Board of Public Welfare.

- Mr. Anonymous: The Story of William Volker, by Herbert C. Cornuelle, 1951; also one of the book titles that appear on the Kansas City Public Library parking garage

- History of Board of Public Welfare, Kansas City, Missouri, 1910-1918, by Mary Lou Fenberg, 1942

- Various books that are a part of the William Volker Fund Series in the Humane Studies; a series funded by William Volker’s estate to examine free-market economics and other libertarian ideas

Continue researching William Volker and the Board of Public Welfare using archival material held by Missouri Valley Special Collections.

- Vertical File: Volker, William

- Vertical File: Welfare Department

- Roselawn: Home of Frederick and Dorothea Volker–photo album

- Vertical File: Residences–Roselawn

- Microfilm: Native Sons Scrapbooks, Roll 15; William Volker

- Vertical File: Fountains–William Volker

- Vertical File: Schools–Public–Kansas City–Volker

Continue researching William Volker using other archival material in the William Volker and Company Records, LaBudde Special Collections, held by the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

References:

Brown, A. Theodore and Lyle W. Dorsett. K.C.: A History of Kansas City, Missouri. Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Company, 1978.

Cornuelle, Herbert C. Mr. Anonymous: The Story of William Volker. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1951.

Ellis, Roy. A Civic History of Kansas City, Missouri. Springfield, MO: Elkins-Swyers Co., 1930.

Haskell, Henry C. and Richard B. Fowler. City of the Future. Kansas City, MO: F. Glenn Publishing Co., 1950.