On December 16, 1936, 1,000 employees of the Fisher Body plant located in the Leeds district of Kansas City sat down on the job to protest the recent firing of a worker and demand that General Motors recognize the unionization of autoworkers. What could have been merely a local dispute instead gave early momentum to one of the most significant labor-management confrontations of the twentieth century, the so-called General Motors Strike of 1936-37.

The national union that led the strike, the United Automobile Workers of America (UAW), was founded in 1935. The UAW soon demanded formal recognition from General Motors and other automakers as a legitimate representative of auto factory workers. The UAW hoped for unprecedented legal support for its efforts due to the 1933 Wagner Act, which for the first time provided federal recognition of workers’ rights to bargain collectively. Despite this legislation, however, the major automakers still resisted unionization of their workers, in part because the Supreme Court had not yet upheld the constitutionality of the Wagner Act.

By 1936, the UAW was considering nationwide strikes to obtain this recognition, along with better working conditions, increased job security, and higher wages. Workers at Fisher Body plants were in a solid position to lead a strike against GM. Since 1926, General Motors owned a controlling interest in the Fisher Body Corporation, which produced most of the car bodies for GM vehicles.

Fisher Body workers endured notably inferior working conditions and less job security than regular GM employees. Additionally, without a steady supply of Fisher car bodies, GM would not be able to keep up with production demands, which were actually recovering robustly from the worst years of the Great Depression. In 1936, GM was the world's largest automaker, supplying 37% of world's total demand for cars and trucks. In that year, GM was earning an after-tax profit in excess of $239 million, which was edging upward toward the $296 million in profits that GM had attained in 1928, when production peaked before the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

On November 18, 1936, workers at the Fisher Body plant in Atlanta, Georgia, held the first sit-down strike against a U.S. automaker. A relatively new term, "sit-down strikes" differed from older versions of strikes because workers physically occupied the factories, thus ensuring that management could not bring in other workers to continue operations. If police took the side of management and attempted to forcibly remove the strikers (as happened to outdoor picketers in 1930), the officers would have more difficulty doing so without damaging the factories. The only drawback was the occasional difficulty in bringing food to the strikers so that they could remain in place.

The UAW workers at the Fisher Body plant in Kansas City adopted the sit-down strategy on December 16, 1936, ostensibly in response to the firing of a UAW employee the day before. The 1,000 Kansas City strikers prepared for the long haul by creating their own informal police force, singing pro-labor music, and holding their own church services. Meanwhile, with no new car bodies being produced by the Fisher plant, the nearby Chevrolet factory in the Leeds district soon shut down as well, and its workers joined the strike. In total, 2,400 Kansas City autoworkers ceased performing their jobs.

If the strike had been simply a response to local issues, it might have been short-lived. Instead, when General Motors offered Christmas bonuses to the Kansas City workers, they refused until the UAW could win national recognition. This insistence largely resulted from the efforts of the UAW’s president, Homer Martin, who from 1932-1934 had been an active labor leader at the Kansas City Chevrolet plant.

Born in Illinois on August 16, 1902, Martin attended William Jewell College in Liberty, Missouri, and later became a Baptist minister in Leeds. In 1932, he left his ministry to join the labor cause, and in 1935 used his oratorical skills to rise to the top of the UAW. On December 17, the day after the Kansas City strike had begun – and nearly a month into the strike in Atlanta – Martin demanded that GM recognize the UAW nationally, not just on smaller issues at individual plants. For a time, then, the UAW relied on the Atlanta and Kansas City strikers to hold their ground until the UAW could organize strikers on a national basis. Had these workers caved in to pressures from GM, the movement might have died.

After December 23, the Kansas City strikers abandoned the sit-down strategy due to their inability to bring food inside the facility. They moved their protests outdoors and continued the strike. In contrast to many previous labor strikes, though, the police did not interfere. On December 28, workers at the Fisher Body plant in Cleveland, Ohio joined the strike, and on December 30, workers at two Fisher Body plants at Flint, Michigan followed suit. In total, 140,000 employees at 50 GM and Fisher plants either joined the strikes or ran out of work due to production stoppages.

By this time, the main strike was centered in Flint, Michigan. Violence erupted there when the National Guard and the local police used tear gas, fixed bayonets, and the threat of gunfire to confront the strikers. Finally, Frank Murphy, the governor of Michigan, helped convince GM to acquiesce. On February 17, 1937, two months after the Kansas City UAW members sat down on their jobs, GM recognized the UAW, forever altering labor relations in the American automobile industry. By 1941, Chrysler and Ford both followed suit and recognized the UAW. For the Fisher Body and GM employees at Leeds, this quickly translated into a wage increase from 45 to 75 cents per hour. For tens of thousands of UAW members nationwide, the successful 1936-1937 strike against GM was an important stepping stone toward attaining middle-class wages and benefits in the 1950s and 1960s.

View images relating to the 1936 General Motors strike and the automobile industry in Kansas City that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

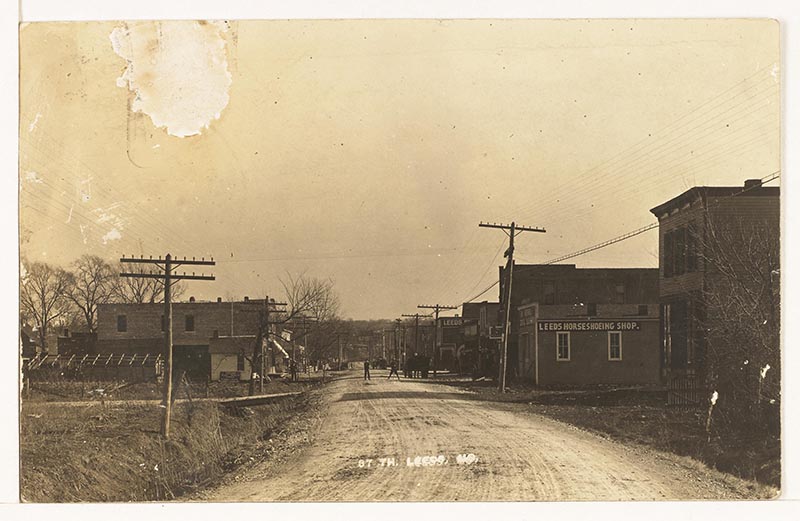

- Older Postcard of 37th Street in Leeds, MO; the general location of the General Motors Fisher Body plant

- Interior view of 1936 Kansas City Auto Show at Municipal Auditorium

- Cars at the Kansas City Auto Show at Municipal Auditorium, circa 1937

- Unidentified Car Assembly Plant, 1930

- Ford Assembly Plant; located at 1025 Winchester Avenue, 1926

- Chevrolet Plant; date unknown

- 1932 Chevrolet Delivery Truck; owned by the City Ice Company

Check out the following articles about the 1936 General Motors strike, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- "Employee Strikes Weave an Historic Thread Through Kansas City," by Dory DeAngelo, in Northeast News, March 12, 2008.

Continue researching the auto industry in Kansas City using archival materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- "Kansas City: Nation's Third Leading Producer of Cars and Trucks," by Earl Morey in Kansas Citian, December 1965.

- Vertical File: Automobiles--History.

- "Automobile Industry," Kansas City Star, February 10, 1929.

- "Ford Closing Stirs Kansas City," Business Week, October 30, 1937.

- Vertical File: Ford Motor Company.

- Vertical File: Labor Unions--United Automobile Workers of America.

- "Birth and History of Local #93 and U.A.W.," published by the UAW, 1978.

References:

Dory De Angelo, What About Kansas City!: A Historical Handbook (Kansas City, MO: Two Lane Press, Inc., 1995), 67-68.

Sidney Fine, Sit-Down: The General Motors Strike of 1936-1937 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 18, 20-22, 78, 138-144, 161, 327.

Sidney Fine, "The General Motors Sit-Down Strike: A Re-Examination," The American Historical Review 70, no. 3 (April 1965): 691-713.

Timothy P. Lynch, "‘Sit Down! Sit Down!:’ Songs of the General Motors Strike, 1936-1937," Michigan Historical Review 22, no. 2 (Fall 1996): 1-10.

George E. Peter, "Sit-Down," American Speech 12, no. 1 (February 1937): 31-33.