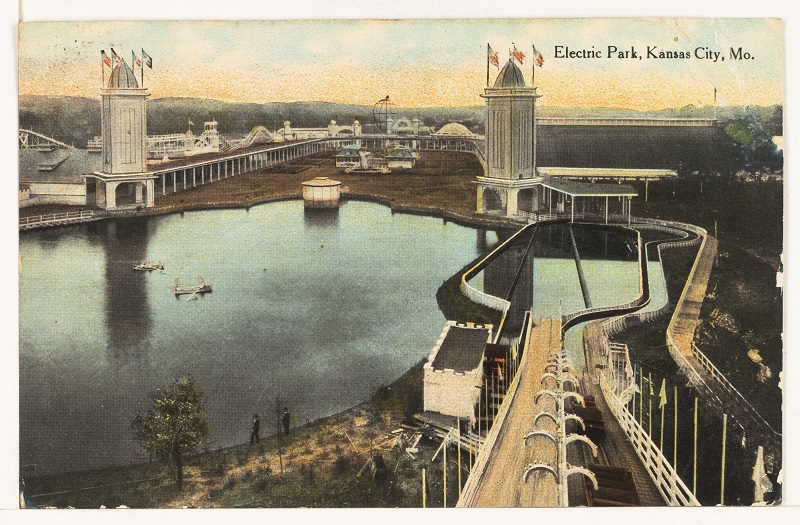

On May 19, 1907, 53,000 people attended the opening day of the new Electric Park. Originally conceived as a ploy to bring customers to visit the Heim Brewing Company in 1899, the park had grown into an attraction in its own right. Each night, the 100,000 lights that gave the park its name illuminated a roller coaster, scenic railway, carousel, skating rink, swimming pool, bowling alley, alligator farm, dime museum, theaters, dance pavilions, bandstand, penny arcade, shooting gallery, flower beds, a lake, and rental boats. Most alluring were the nightly performances of costumed young women who danced to a colorful electric light show on a platform on a large fountain in the center of the lake. The park, sometimes known as Kansas City's Coney Island, continued to serve the city's greatest amusement park for nearly two decades.

The first and second Electric Parks were built by brothers Joseph, Ferdinand, and Michael Heim, owners of the Heim Brewing Company. As brewers, the brothers followed in the footsteps of their father, a brewer named Ferdinand Heim, Sr. Ferdinand had emigrated from Austria to the United States in 1854, where he operated a small brewery in Manchester, Missouri from 1857-1862, and a larger one in East St. Louis from 1870-1889. As an expansion of this business in 1884, Ferdinand and his three sons jointly purchased the Star Ale Brewery in the East Bottoms of Kansas City, and specialized in the brewing of German lager beer.

The three brothers quickly built the Heim Brewing Company into the largest capacity pre-prohibition brewery in Kansas City. Beyond their success in beer-making, though, the Heim brothers took an interest in technological novelties. They were the first in Kansas City to open a telephone exchange and operate a 25-horsepower steam engine. They designed the original vertical top-loading icebox. Ferdinand, Jr., was the first Kansas City resident who drove an automobile with a back seat.

One of their riskiest and most important ventures was the construction of a $96,000 streetcar line from the Market Square that would carry visitors directly to the brewery to buy fresh beer. At first this very expensive investment was a dismal failure. Instead of abandoning the venture, the brothers decided to open an amusement park, called Electric Park, at Chestnut and Guinotte, to attract riders on the streetcar and perhaps visitors to the brewery. The Heims' streetcar line soon carried droves of passengers to the amusement park, allowing them to sell the line for $250,000.

In addition to a roller coaster, other rides, fountains, a vaudeville theater with seating for 2,800, a dance pavilion, and gardens, Electric Park provided a giant German-style beer garden. A pipeline carried beer from the nearby Heim brewery directly into the garden. The arrangement was perfect for business because the still-novel electric lighting provided an illuminated experience after dark, when thousands of day workers and their families wanted to leave home to relax and play. In short, it was the most popular working class entertainment venue available in Kansas City.

In the early 1900s, the city was expanding toward the south, and the Heim brothers determined that Electric Park should follow. They picked a location at 47th and The Paseo, and built a larger, 27-acre Electric Park there. The old Electric Park closed, and the new one opened on May 19, 1907, to a boisterous crowd of 53,000. Despite the Heim brothers' close involvement, no beer was available at the second park: a city ordinance now prohibited its sale there. Nonetheless, the park thrived with carryovers as well as additional amenities such as an alligator farm, a shooting gallery, and lake and boat rentals.

The Living Statuary, which featured elaborately-costumed female dancers and a colorful light and water show, was one of the most popular nightly attractions. Equally as important was the bandstand, which attracted top performers, sometimes including "The March King," (the infamous American composer and conductor John Philip Sousa). Sousa reportedly remarked that the bandstand at Electric Park was the best in which his band had ever played.

Amusement parks and other forms of entertainment ebb and flow with popular whims, and Electric Park was no exception. By the 1920s and 1930s, radio and movies drew interest away from amusement parks, and the lights, fountains, and rides of Electric Park were no longer a great attraction. In 1925, a fire spread through the park and destroyed many of its buildings. Swimming and public dances remained popular there until a second fire in 1934 forced what remained of the park to shut down. The Heim brothers could not reinvest in the park because the Heim Brewing Company went out of business after national Prohibition began in 1920. In 1948, the remnants of the Electric Park roller coaster were razed to make way for the Village Green Apartments at the same location. By then, all three of the Heim brothers had passed away, and their entrepreneurial legacy had largely disappeared.

View images of Electric Park that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Postcard view of the second Electric Park; accompanied by a brief historical article

- Postcard of the flower beds at the second Electric Park; accompanied by a brief historical article

- Postcard of Heim's (first) Electric Park in the East Bottoms; accompanied by a brief historical article; see a second historical article here

- Postcard of East View From City Point; shows the Heim Brewery, accompanied by a brief historical article

- Heim Brewery and the first Electric Park, 1900

- Cineograph Theater at the first Electric Park, 1900

- Flood Scene showing the first Electric Park and Heim Brewery, 1903

- Heim Brewery and the first Electric Park, 1905

- Entrance to the second Electric Park, 1910

- Electric Park at Night, 1910

- Electric Park natatorium, pool, and roller coaster, 1910

- Electric Park Roller Coaster, 1910

- Electric Park Visitors, 1910

- Woman Posed Atop Fountain at Electric Park, 1910

- Village Green Apartments at the former site of Electric Park, 1950

View images of Electric Park on the Kansas City Public Library's Flickr® photostream.

Check out the following books and articles about Electric Park, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- "Electric Park: Kansas City's Coney Island, 1900-1925," by Craig M. Bryan, in the Jackson County Historical Society Journal, Autumn 2006, pp. 3-9; see original version in the Missouri Valley Special Collections, June 19, 1905.

- "Mass Commercial Amusements in Kansas City before World War I," by Alan Havig, in the Missouri Historical Review, April 1981, pp. 316-345.

- "A Post Card from Old Kansas City," in The Kansas City Star, July 5, 1969; discusses a post card showing the main entrance to the second Electric Park.

- "A Kansas City Novelty Figures Importantly in History of Movies," in The Kansas City Star, September 20, 1939; discusses the Hale's Tours movie shows, which debuted in 1905 at the first Electric Park.

- "Heim Brothers Left Mark on Kansas City," in Northeast World, December 2, 1987.

Continue researching the Electric Park using archival materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Mrs. Sam Ray Postcard Collection Finding Aid; contains images of Electric Park

- Vertical File: Parks--Kansas City--Electric

- Photo of "Heim's Electric Park," View of Kansas City, MO, 1905, p. 43

- Vertical File: MacMorris, Daniel; sculptor of gargoyles on the tunnel of love at Electric Park

- SC63, Parks-Electric

- "Kansas City's Coney Island," in Kansas City World, July 27, 1902, microfilm

- Missouri Valley Special Collections Postcard Collection Finding Aid; contains postcards of Electric Park

- Dory DeAngelo Papers Finding Aid; contains photographs of Electric Park

- Photo of "Heim's Theatre, Electric Park," 1902

- Photo of the "interior of Heim's Theatre, Electric Park," 1902

- Vertical File: Breweries--Heim Brewery

- Advertising cards for the Ferd. Heim Brewing Co.

References:

Michael G. Bushnell, Historic Postcards from Old Kansas City (Leawood, KS: Leathers Publishing,2003), 42.

Dory DeAngelo, What About Kansas City!: A Historical Handbook (Kansas City, MO: Two Lane Press, 1995), 118-120.

Dory DeAngelo & Jane Fifield Flynn, Kansas City Style: A Social and Cultural History of Kansas City as Seen through its Lost Architecture (Kansas City, MO: Harrow Books, 1990), 70-71.

H. James Maxwell & Bob Sullivan, Jr., Hometown Beer: A History of Kansas City’s Breweries (Kansas City, MO: Omega Innovative Marketing, 1999), 129.

Mrs. Sam Ray, "Amusement Parks," Kansas City Times, June 3, 1973.

Mrs. Sam Ray, "Electric Park (1st)," The Kansas City Times, June 20, 1973.

Mrs. Sam Ray, "Electric Park (2nd), Flower Beds," The Kansas City Times, August 23, 1985.