The beginning of the end came for the Kansas City Stockyards in July 1951 when the West Bottoms suffered the worst flood in the city’s history, one from which the industrial district never fully recovered.

Standing on the second floor of the Livestock Exchange Building, one can see the high-water mark of the 1951 flood. Causing nearly a billion dollars in damage and the loss of lives and homes, it shocked the city, region, and nation. The destruction changed the course of history for the Central Industrial District and the Kansas City Stockyards, although it was hardly the first time the Missouri and Kansas rivers had overflowed their banks in the West Bottoms.

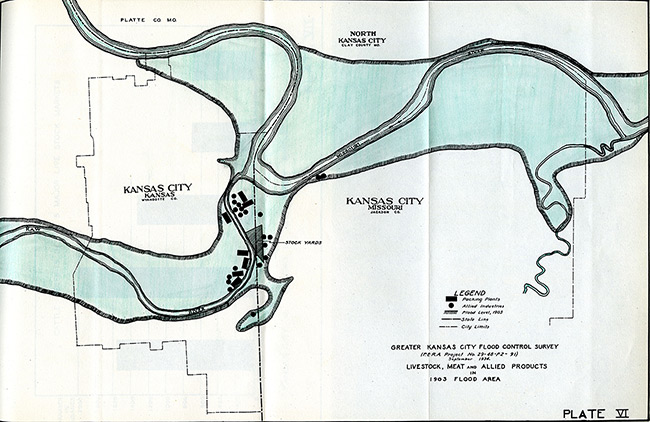

The valley where the Kansas and Missouri rivers meet has always been a flood zone, even before the area was settled. As the railroads, stockyards, and other industries arrived after the Civil War, their gradual encroachment on the river banks started shrinking the mouth of the Kaw River. By 1903, the width had diminished nearly by half and 17 bridges crossed the river within a four-mile span between the Argentine neighborhood and the Kaw’s mouth.

The Kansas River breached its banks on May 30, 1903, and reached a height of 14 feet above flood stage. By the time the waters subsided and the destruction could be surveyed, 19 lives had been lost, over 23,000 people had lost their homes, 16 of the 17 bridges were destroyed, utilities were out of service, and approximately $22 million in damage had been done.

In the wake of this flood, West Bottoms stakeholders agreed on the need for a flood control plan. Business owners, leaders of state and federal government agencies, and individual citizens debated what should be done and how much money should be expended. A Special Board of Government Army Engineers was formed to investigate the flood and recommend solutions. The engineers issued a report that advised reinforcement along the river banks, widening the distance between the tops of the banks to 734 feet, dredging the river bed, and requiring all bridges to conform to a two-pier plan.

The Kaw Valley Drainage District organized in 1905, under the authority of the State of Kansas, to oversee natural waterways in its territorial limits and be in charge of flood control matters. The district board again investigated the river, and made the same recommendations for flood control as had the board of engineers. These recommendations were met with fierce opposition from the railroads and other industries in the area, which believed the 1903 flood to be an anomaly and long-term flood protection on such a large scale unnecessary. Litigation ensued between the drainage board and corporate interests.

Following the 1908 flood, and at the insistence of the drainage board, Congress approved the establishment of harbor lines in 1909 along the Kansas River, allowing for the widening of the river banks. But other improvements continued to be delayed.

In 1919, consulting engineer C. E. Smith was commissioned by corporate interests in the area to report on “improvements that are reasonably necessary to complete the flood protection of the Kaw River within the Kaw Valley Drainage District.” The report claimed the proposal of the Drainage Board was excessive and that adequate protection could be achieved with more affordable improvements.

By 1934, local interests already had contributed millions of dollars to flood protection as numerous small floods continued to wreak havoc in the Kaw Valley and West Bottoms. By this time, it was widely agreed that a more permanent solution with the help of federal aid was needed.

New Deal programs guaranteed that federal funding would be available. The Army Corps of Engineers had proposed three different plans, all of which failed to gain enough support. The two Kansas Cities formed a Joint Committee on Flood Protection that included 44 members from industry, transportation, Chambers of Commerce of the two cities, and other area interests. In response to the plans proposed by the Army, the Joint Committee compiled a survey with the help of the Jackson County Emergency Relief Committee and submitted it to the Mississippi Valley Committee National Resources Board in 1934. This “Survey of the Economic Aspects of Flood Protection” concluded that further detailed studies should be made.

Furthermore, it said, “On account of the national economic importance of the Kansas Citys from the standpoint of manufacturing and employment, distribution and transportation, and since this immediate flood area has expended approximately $13,150,000 for flood protection, it is the judgment of the committee that completion of works for the adequate protection of these communities and the flood plain of the Kansas River upstream is a logical federal responsibility.”

In 1935, the Joint Committee on Flood Protection commissioned Frederick Fowler, a consulting engineer, to study which plan would be best for controlling the two rivers. His 1937 report recommended tributary reservoirs rather than local levees. Flood Control Acts in 1936 and 1938 required the federal government to help finance flood control projects, pushing local committees to compromise on a solution.

In 1944, a joint proposal from Army Engineer Lewis Pick and William Sloan of the Bureau of Reclamation was approved by Congress. The proposal, which called for 112 dams, hundreds of miles of levees, and other flood protection structures, would take years to complete, but it was the most ambitious and promising plan yet to control the rivers in the Missouri River basin.

It was while the Pick-Sloan program was slowly being implemented that the disastrous 1951 flood struck the West Bottoms. The Central Industrial District was ravaged. Businesses were disrupted for weeks, and many including the stockyards never fully recovered. The cost of the flood was far higher than that of any previously proposed flood-control plans, and the different factions finally were united in support of proceeding with the Pick-Sloan program.

Aerial views of 1951 flood - At left: View of West Bottoms, showing Livestock Exchange Building

At right: Looking east from near the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas River

Building a city around a valley where two major rivers meet was advantageous for ease of transportation, access to natural resources, and the promise of economic growth. Conversely, it presented a whole set of complex political, economic, and environmental complications. As an industry wholly affected by a history of destructive floods, the Kansas City Stockyards papers provide access to the many sides of the flood control controversy.

References:

Harrington, Grant W. Historic Spots or Mile-Stones in the Progress of Wyandotte County, Kansas. Merriam, Kansas: The Mission Press, 1935.

Joint Committee on Flood Protection of the Chamber of Commerce of Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, Chamber of Commerce, “A Survey of the Economic Aspects of Flood Protection on the Kansas and Missouri Rivers in the Kansas City District,” submitted to the Missouri Valley Committee of the National Resources Board, Washington, D.C. (October 1934). Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library.

Nimz, Dale. “Damming the Kaw: The Kiro Controversy and Flood Control in the Great Depression.” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 26 (Spring 2003): 14-31.

Smith, C.E. “Report Submitted to Property Owners in Kaw Valley Drainage District Defining Additional Improvements Required for Flood Protection Along the Kaw River Kansas City, Kansas.” Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library.