What’s the saying? One man’s trash is another’s treasure?

Lucinda Adams recalls the day, five years ago, when she and a couple of members of the Library’s facilities staff were led into a converted storage room in the old Kansas City Livestock Exchange building in the city’s West Bottoms.

The place hadn’t been touched for decades and it looked it — dusty and unkempt, hundreds of drawings and other documents in piles or strewn across the floor.

“The entire floor was covered,” says Adams, lead archivist for the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections. “Some (of the documents) were rolled. Some were flat. Pieces were breaking off.”

It was history for the taking.

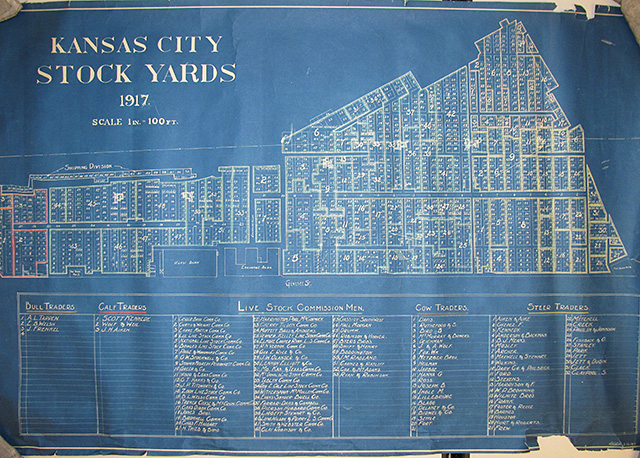

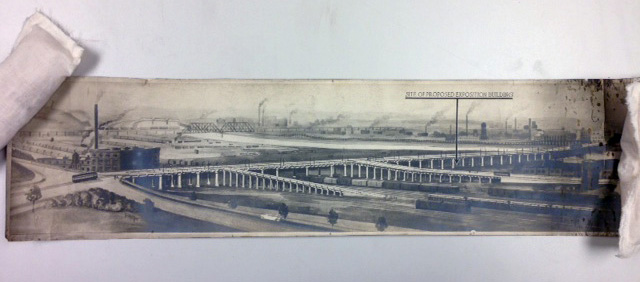

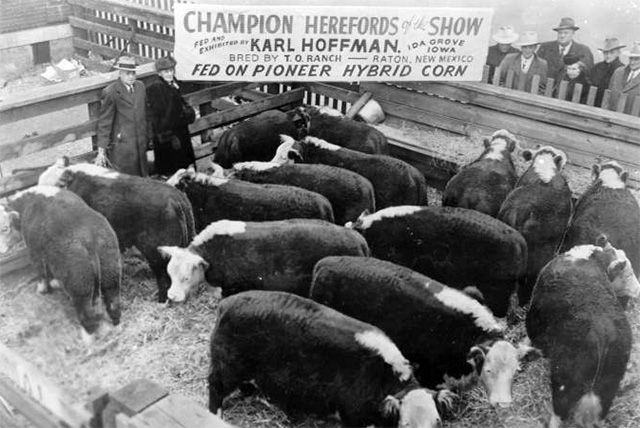

The items — some 5,000 in all — included blueprints and architectural drawings of the iconic Kansas City Stockyards, revealing details down to the specially designed nails and screws used in the wooden livestock pens. There were photos and maps. Many of the documents appeared to have come from the office of the chief engineer who supervised the Stockyards’ construction and development in the late 1800s.

West Bottoms businessman Bill Haw, now the building’s owner, was clearing it out before renovating the historic structure at 1600 Genessee. Whatever the Library wanted from the makeshift storage room, he told Development Director Claudia Baker and later Adams, it could have.

Workers filled nearly four dozen refrigerator-size boxes.

With a $101,000 grant announced Tuesday from the Washington, D.C.-based Council on Library and Information Resources, the Library will sort and catalog the collection over the next two years and make it available to researchers. The items also will be spotlighted in an exhibit opening at the Central Library in spring 2014.

Baker and MVSC Manager Eli Paul still marvel at the find. “Basically,” Paul says, “you could rebuild the Stockyards based on the detailed maps, blueprints, and other documents we have.”

The collection sat in storage at the Black Archives of Mid-America until earlier this year, when a private donation allowed the Library to complete an initial inventory. With the grant from CLIR, a nonprofit whose Hidden Collections program promotes public access to “items of potentially substantive intellectual value,” the Library now can properly arrange the long-lost documents, explore and write descriptions, and make the collection available to researchers.

The Kansas City Public Library is one of 22 libraries, museums, and other institutions and organizations across the country receiving the grants, which are underwritten by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

The work the money will underwrite “is a perfect fit with our long-range goals of collecting, preserving, and making accessible Kansas City’s history,” Paul says.

Sometimes, the starting point is unexpected. One messy room in a now-more-than-century-old building. A phone call and an offer.

“He said, ‘I’ve got all this stuff. Do you want it?’” Adams recalls Haw saying back in 2008. “There was no warning, no preparation.”

And no hesitation. Adams said yes.