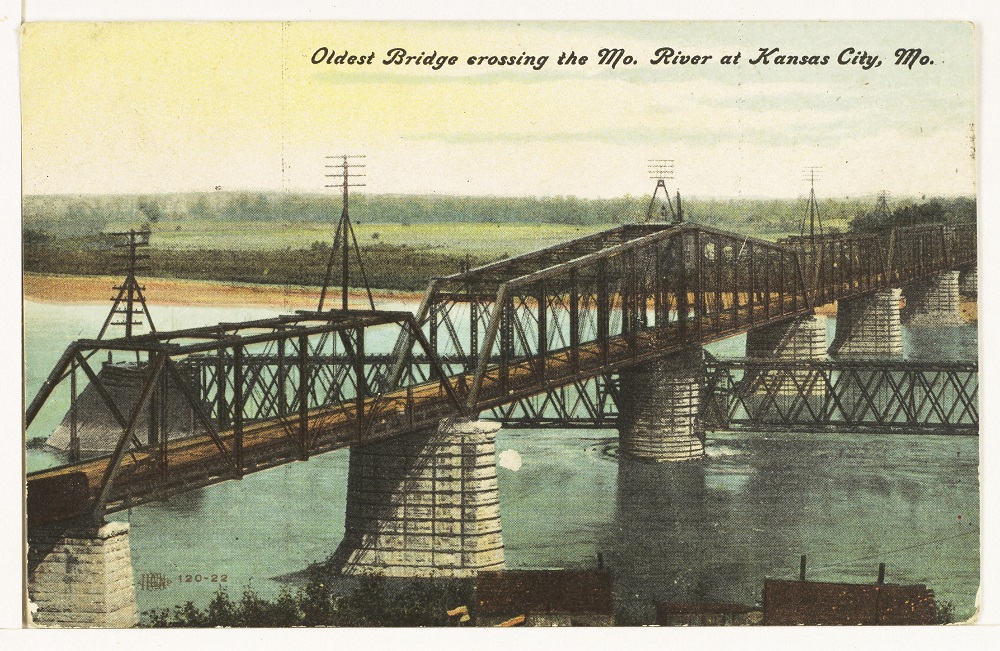

July 3 marks the 150-year anniversary of the opening of the first rail crossing over the Missouri River. While the current Hannibal Bridge is a replacement completed in 1917, raising a toast to its predecessor certainly seems in order. After all, Kansas City as we know it today likely would never have existed without it.

The Idea

Back in the 1830s, when a group of Westport traders began landing their goods at a limestone shelf near today’s River Market, the settlement that was to become Kansas City was a place of big ideas. One was to build the first rail crossing over the Missouri River. That would give Eastern markets access to the vast territories of the American West, and the subsequent flow of goods and people figured to prime the city for an economic boom.

Getting the Bridge

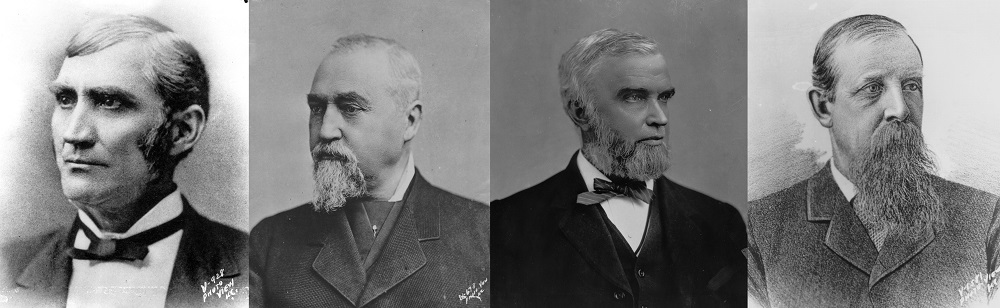

Kansas City was not without competitors as Leavenworth, St. Joseph, and Atchison also looked to position themselves as commercial hubs. In KC, business and civic leaders including Kersey Coates, Charles Kearney, Robert T. Van Horn, and Theodore Case took on the challenge of securing the bridge for their city. Overtures were made to railroad interests as early as the 1850s, but the growth of the young city and momentum for the bridge were stunted by the outbreak of the Civil War.

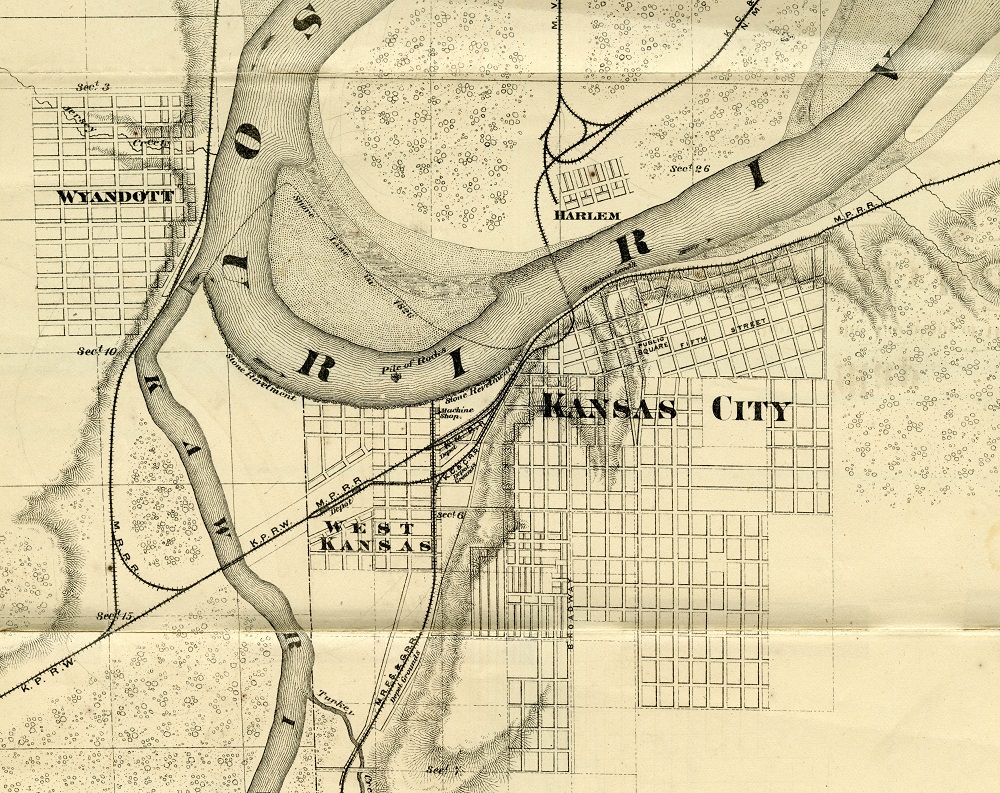

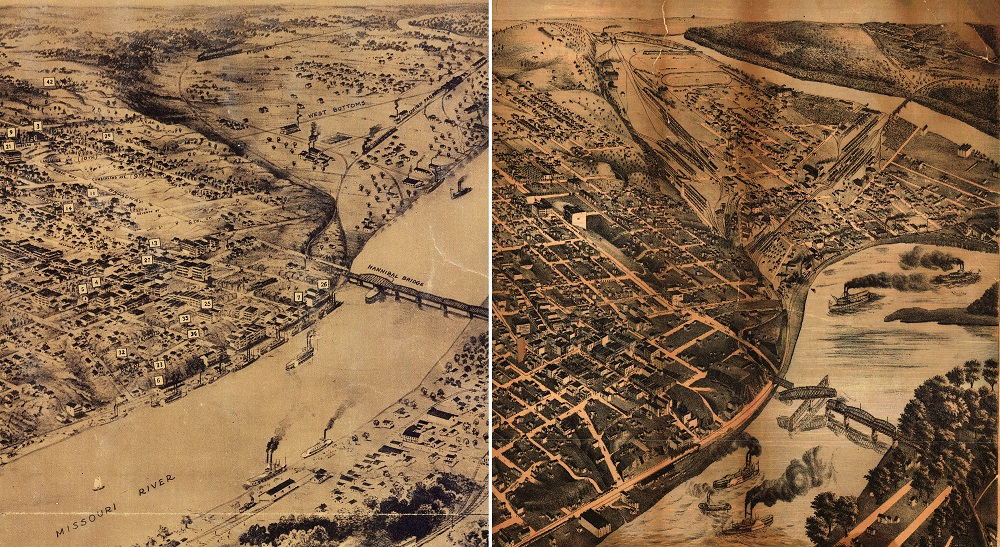

With the war settled in 1865, progress on the bridge idea could continue. Beyond old-fashioned civic boosterism, the advantages of Kansas City’s position at the confluence of the Kansas (or Kaw) and Missouri rivers helped sway the decision in its favor. A bridge here would not only provide access to the Western territories but also spare the trouble and expense of almost immediately needing to bridge the Kaw, too, in order to access the Southwest – a benefit unique to Kansas City among the bridge-site frontrunners.

Boosterism and geographic advantage aside, Kansas City still may have lost out on the bridge if not for the business acumen of Coates and Kearney. Along with other investors in the West Kansas Land Company, the duo had been buying up real estate in today’s West Bottoms. At the zero hour, just as Leavenworth was closing in on a deal for the bridge, the duo shrewdly agreed to sell a portion of their significant land holdings in the West Bottoms to the president of the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad. Just like that, the decision was made. Kansas City had its bridge.

With Kansas City now serving as the connecting point between Eastern markets and the American West, the livestock industry was set up to explode – you guessed it, in the West Bottoms land owned by many of the bridge’s biggest promoters.

Building the Bridge

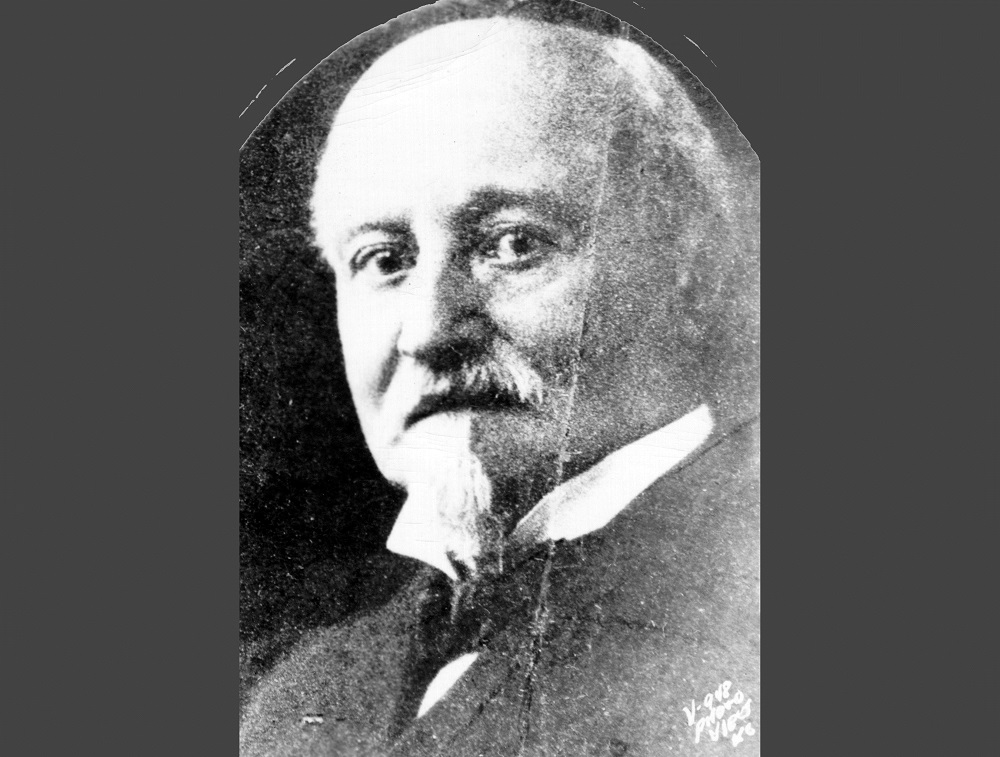

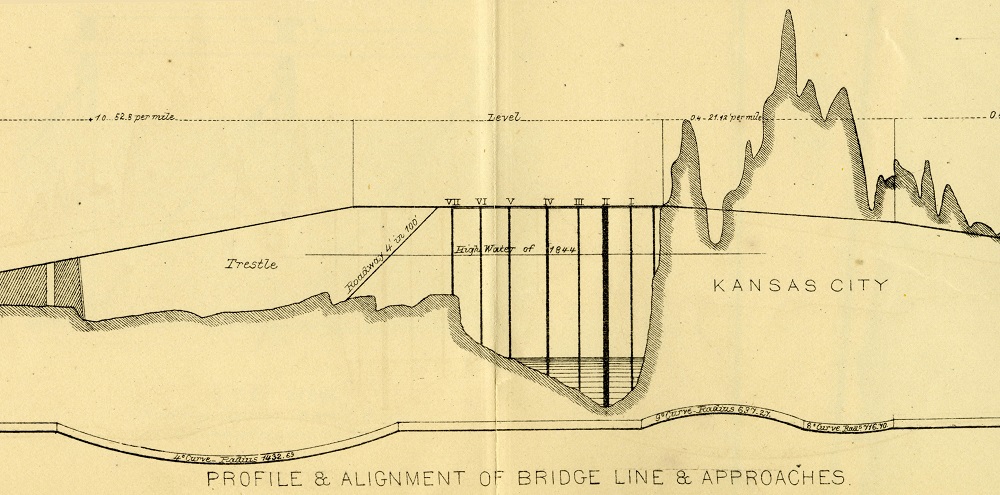

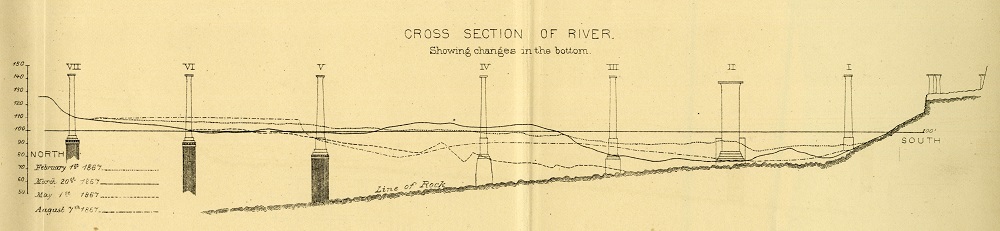

Of course, the bridge needed to be built before anyone could benefit from it. The most obvious obstacle was the river itself, but there are other characteristics of the Missouri that made its spanning a unique challenge. First, it was prone to periodic flooding. Memories of a terrible flood in 1844 still lingered with early Kanas City residents. Floods often led to another problematic trait: the river’s tendency of to shift its course. With its rocky bluffs, a bridge could be secured to the southern bank with relative ease. But the flooding and shifting course of the river left even the dry land on its northern bank a silty and sandy mess. To solve these problems, bridge financiers turned to a young, self-trained civil engineer and transplanted Parisian, Octave Chanute.

Chanute moved his family to Kansas City in 1867 and threw himself into the challenge. He wanted to learn as much as he could about the 1844 flood and picked the brains of longtime residents to locate highwater marks. His bridge would need to be high enough to avoid damage during a historic flood but not so high that the grade into the West Bottoms became too steep for heavily loaded trains to safely descend. The greatest test of his calculations came with a late spring flood that killed 19 people in Kansas City in 1903. The bridge remained above the waterline and unscathed.

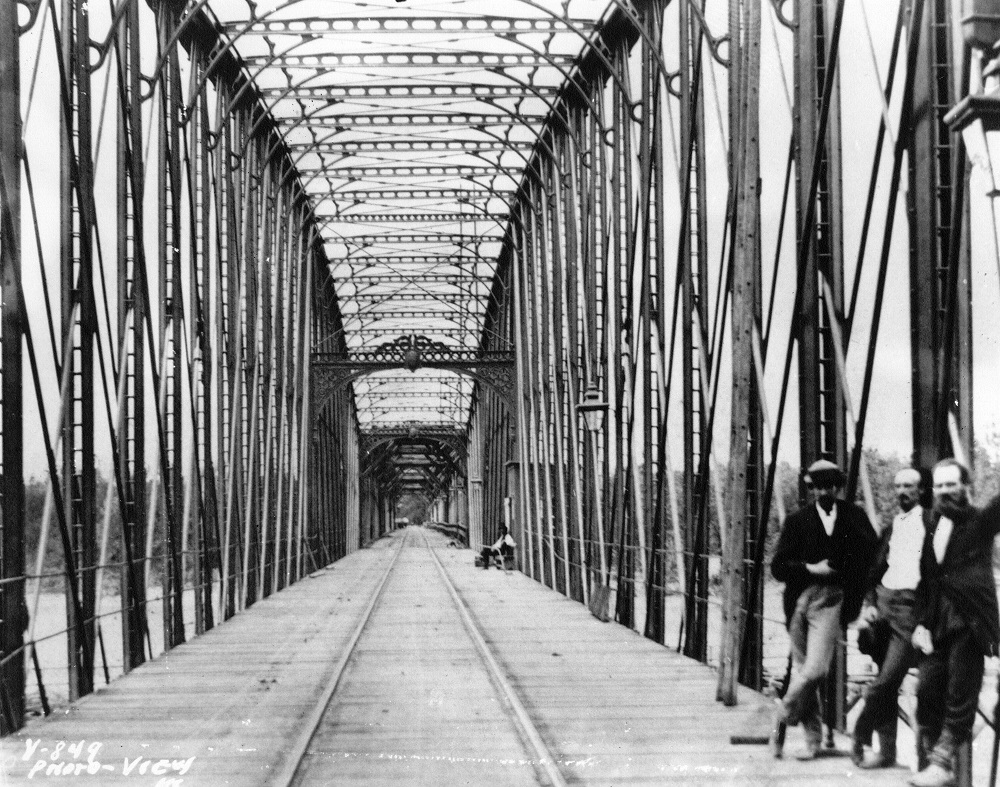

To address the shifting nature of the river as well as its uneven bottom, Chanute realized that each pier would need to be uniquely designed to suit its location. Near the southern bank, custom-made concrete footings were attached to the river’s rock floor to support Piers 1 through 4. Piers 5 through 7 to the north were more challenging, requiring oak piles to be sunk into the sandy bottom to support them.

To facilitate construction, Chanute designed wooden caissons – watertight structures used to perform work beneath the river’s surface – and brought in water jets to pump out sand and silt. He hired divers to install the caissons and move boulders and other debris standing in the way of progress. Despite the inherent danger of working in the Missouri’s muddy waters, no accidents were reported by the dive team.

Thanks to Chanute’s extensive planning, overall work on the bridge progressed with few setbacks. The pace even was quickened when railroad executives wanted the structure completed ahead of schedule to compete with other advancing lines. Chanute’s simple addition of wooden planks around the rails allowed carriages to cross as well, avoiding the need for a separate span and saving the railroad time and money. Carriages were charged tolls. And when a foot bridge was added along the west side of the bridge, pedestrians were charged, too.

Opening the Bridge

The bridge was functionally complete on June 15, 1869, when the draw was rotated for the first time. Its structural integrity was tested on July 2 when a fully loaded, four-car train passed over the Missouri River for the first time.

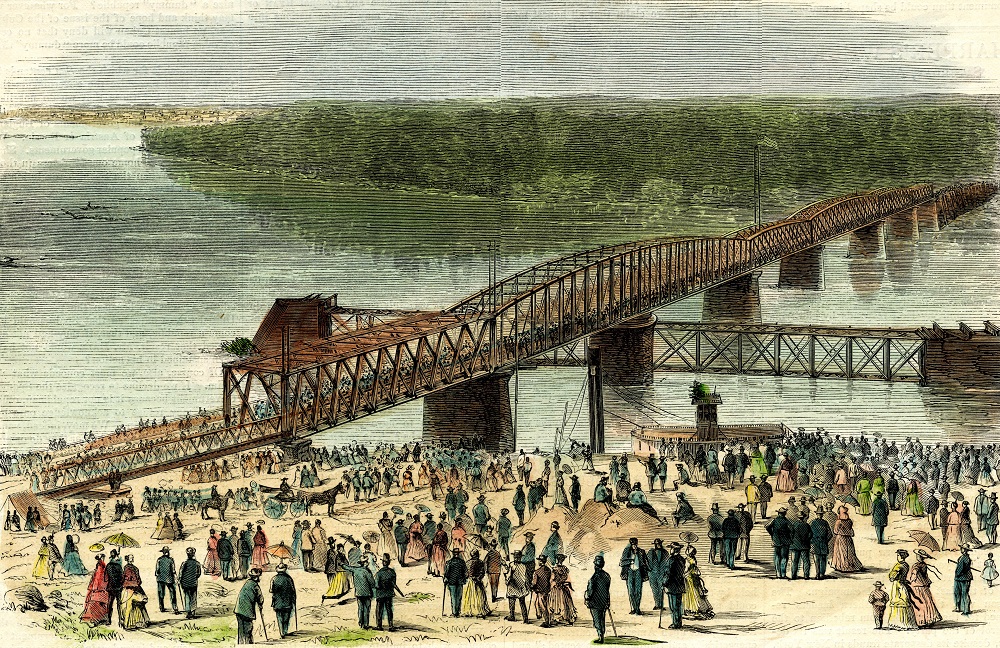

Kansas City would never be the same. With the coming of the railroads, commercial activity became less and less focused on the river with each passing year. Soon, Main Street would replace the riverfront as the city’s center of business activity and the Stockyards became a hub of the midwestern agricultural world. So long, river town. Hello, Cowtown (and all of the unflattering references to follow). But this was not a time for lamenting what the future could bring; it was a time to celebrate. And with an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people in attendance, celebrate the city did.

Below is a transcription of the opening ceremony for the bridge:

Programme of the BRIDGE CELEBRATION at Kansas City, Mo., on July 3, 1869!

The procession will be formed under the direction of the grand marshal and his aids on Fifth street, with the head of the column resting on Wyandotte street, at 10 o’clock a.m., precisely, and will move thence down Fifth street to Broadway, thence down Broadway to the south end of the bridge, in the following order:

Music – Lafayette Silver Cornet band of Lexington.

1. O. Chanute, Esq., the chief engineer; the mayor of Kansas City, and the orator of the day, followed by the city council and invited guests in carriages, escorted by the Knights Templar as a guard of honor. Music – Wyandotte band.

2. The various Odd Fellow lodges of Kansas City and their visiting brethren.

3. The Royal Arch Chapters, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons, followed by the various Masonic lodges of the city and their visiting brethren.

4. The Good Templars and the Temple of Honor, and their visiting brethren. Music – Paola band.

5. The Bridge Mechanics.

6. The officers and Men of the Hannibal & St. Joseph and other Missouri and Kansas railroad companies and the transfer company.

7. City mechanics.

8. City contractors and employees, butchers and draymen.

9. Citizens and visitors generally.

On arriving at the Bridge the column will be halted to witness the testing of the Bridge and the passage of trial trains, under the supervision of a committee of Engineers, after which the procession will move across the Bridge to the grounds beyond, where a greeting will be extended by the Mayor of Kansas City to the citizens of Clay and Adjoining counties.

The procession will then reform, and, accompanied by the delegations from Clay and adjoining counties, recross the Bridge and proceed to the grove in General Steen’s pasture; passing along Broadway to Third street, thence along Third street to Delaware, thence along Delaware to Fourth street, thence along Main street to Chestnut, thence along Chestnut to Walnut street, thence along Walnut street to Ottawa street and thence to the Grove, where an oration will be delivered by Gen. John A. McClernand, Orator of the day.

After which all present will partake of a GRAND BARBECUE, On the Grounds, when the ceremonies of the Day will end.

During the recrossing of the bridge Mr. H. R. Holman will make a BALLOON ASCENSION from the south end of the bridge.

The Kansas City Bridge Collection

To celebrate the 150-year anniversary of the Hannibal Bridge, the Kansas City Public Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections is happy to make available to the public a digitized copy of the 1870 book by Chief Engineer Octave Chanute and Assistant Engineer George Mason about the design and construction of the Hannibal Bridge. Many of the photographs and illustrations accompanying this article were scanned, and can now be accessed online.