Kansas City Cattle King: Relics of the Stockyards

“Paris of the Plains,” the “City of Fountains,” and more recently the “Soccer Capital of America” are all names that come to mind when one thinks of Greater Kansas City. Or at least that’s how boosters have tried to promote the city in an effort to shed its stereotypical Midwestern “cowtown” reputation.

Kansas City has transformed itself geographically, demographically, economically, and culturally since the days when the Stockyards occupied the West Bottoms, but to forget the city’s livestock industry roots does a disservice to its unique and rich history.

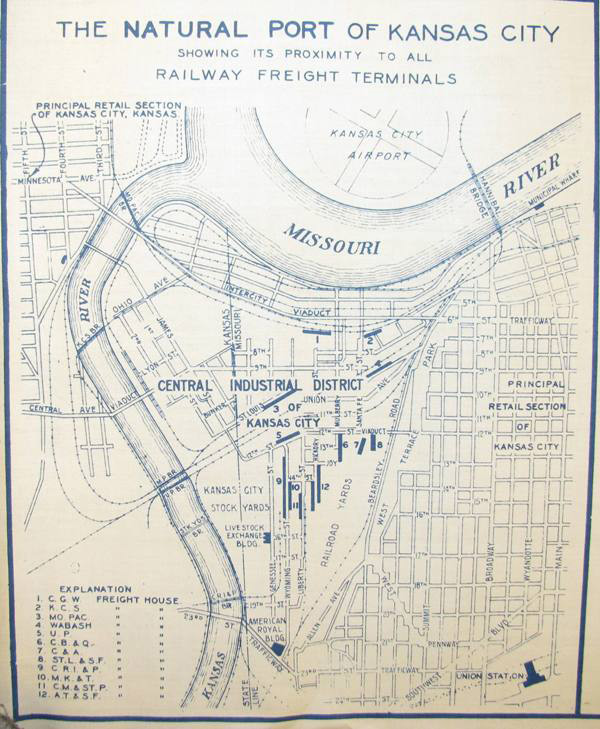

Arguably the transformation of the humble Town of Kansas to the bustling metropolis of Kansas City paralleled that of the livestock trade and meat packing industry. With the West Bottoms situated at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, business interests were naturally drawn to the area. The rivers offered shipping routes and easy access to natural resources.

With the completion of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869, the first bridge to cross the Missouri River, an important link was formed between the East and West. As plans for a transcontinental railroad system were established, developers lobbied for a terminal in Kansas City, and the Union Depot was opened in April 1878. All these factors led to the birth of the Kansas City Stock Yards Co. in the West Bottoms of Kansas City, which grew to be the second largest livestock trader in the nation.

The integration of industry, commerce, and agriculture—arising from relationships among the Kansas City Stock Yards Co., the American Royal, meat packing plants, factories, railroad terminals, and livestock commission firms—allowed each entity to thrive from the success of the others. Railroad men provided shipment of animals and resources. Commission firms helped facilitate smooth transactions between the buyers and sellers. The Stock Yards Company provided a place for the livestock business to be conducted. Meat packing plants bought the animals and turned them into meat for consumption. Area factories used slaughterhouse waste to manufacture useful products. And the American Royal promoted the raising of premium livestock.

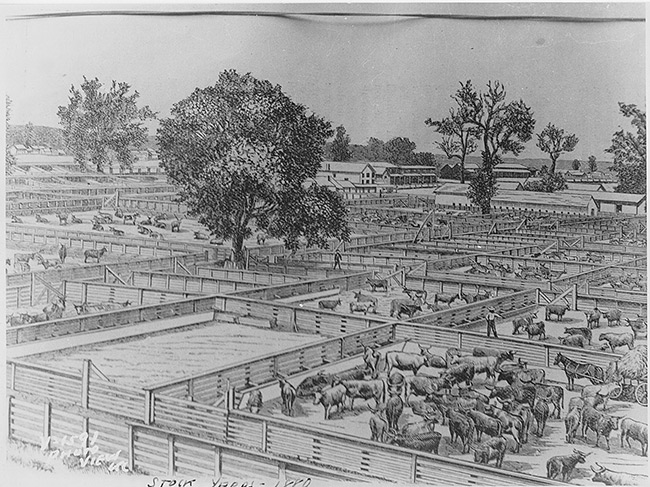

By 1914 the Kansas City Stock Yards covered over 200 acres, had a daily capacity of 170,000 animals, and employed over 20,000 people. It was receiving stock from 35 different states and shipping stock to 42 different states, Canada, and Mexico. When the Livestock Exchange Building, today an iconic West Bottoms fixture, was built in 1911, it was the largest such building in the world. The year 1919 saw the completion of numerous improvements and updates to the stockyards facilities, prompting a writer for the Kansas Citian to boast, “Kansas City now has the best and most equipped yard in the world.”

Nevertheless, Kansas Citians often downplayed the cowtown reputation, thinking it provoked an image of backwater middle America. The clash of eastern influence and western sentiment has always caused Kansas City to have a bit of an identity crisis. While city leaders made great strides toward diversifying its image beyond that of a cowtown, Kansas City remained, and to this day remains, a dominant force in agribusiness. Although the cattle pens and meat packing plants have moved to the region’s rural fringes, companies in the greater Kansas City region lead the nation in the animal health and nutrition industry, as part of the “Animal Health Corridor.”

The West Bottoms, today an area of mostly unused space and abandoned structures, has only a few remnants of the sprawling stockyards that once so clearly identified Kansas City as a world leader in agriculture and industry. A renovated Livestock Exchange Building and thriving American Royal remain as both relics of a glorious past, and testaments to an enduring heritage.

A recent grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources has allowed the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections Department to begin processing a collection of materials from the Kansas City Stockyards. This array of thousands of historical documents—including daily correspondence, maps, blueprints, land abstracts, and photographs—brings renewed life to the story of Kansas City’s cowtown legacy.

By examining these records, we can follow the evolution of its role in one of our nation’s most essential enterprises. Funding for this project has been provided by the Council on Library and Information Resources as part of the Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives initiative, which is generously supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.