Late on the morning of May 5, 1921, Mrs. William A. Huddleston came out of the First National Bank at 10th and Baltimore and met with her boss, J.P. Prescott. (As I write this I am sitting on the fifth floor of the same building, though the building had only four floors 90 years ago.)

Mrs. Huddleston’s husband also worked for Mr. Prescott, as a finisher in the factory at 904-906 E. 12th Street.

Although the Kansas City Star account only gives her name as Mrs. William A. Huddleston, according to the 1920 US Census we know that her first name was Nellie. She worked as the bookkeeper for Prescott’s company.

James Davis, Prescott’s black chauffeur, started the car as Nellie came out of the bank, carrying a black bag that held the $2,063.03 payroll for the 80 workers at the factory. Davis shifted gears, and headed the car toward 12th Street.

The driver of the roadster that followed them was discrete enough that none of the three in the Prescott car noted it.

There were probably no other vehicles on the street, because when Davis approached the front of the building and stopped the car, and Nellie Huddleston got out to take the black bag into the building, the roadster slowed and the other two men quietly and quickly got out. The driver let his car continue moving slowly forward. Well-dressed (one in a brown suit and the other in dark blue) and young looking, the two moved quickly across the street, where one of them grabbed the bag, trying to wrench it from Nellie’s grasp. She squeezed the handle tighter, but the other robber smashed his fist sharply into her wrist, forcing her to let go.

Prescott leaped from the car and tried to tear the bag from the robbers, but the second robber, who apparently had no difficulty beating those older and weaker than himself, knocked Prescott to the ground where he sat dazed, watching the car speed away until Mrs. Huddleston helped him up.

The police later found the car, which had been stolen, abandoned in the 3500 block of College Avenue.

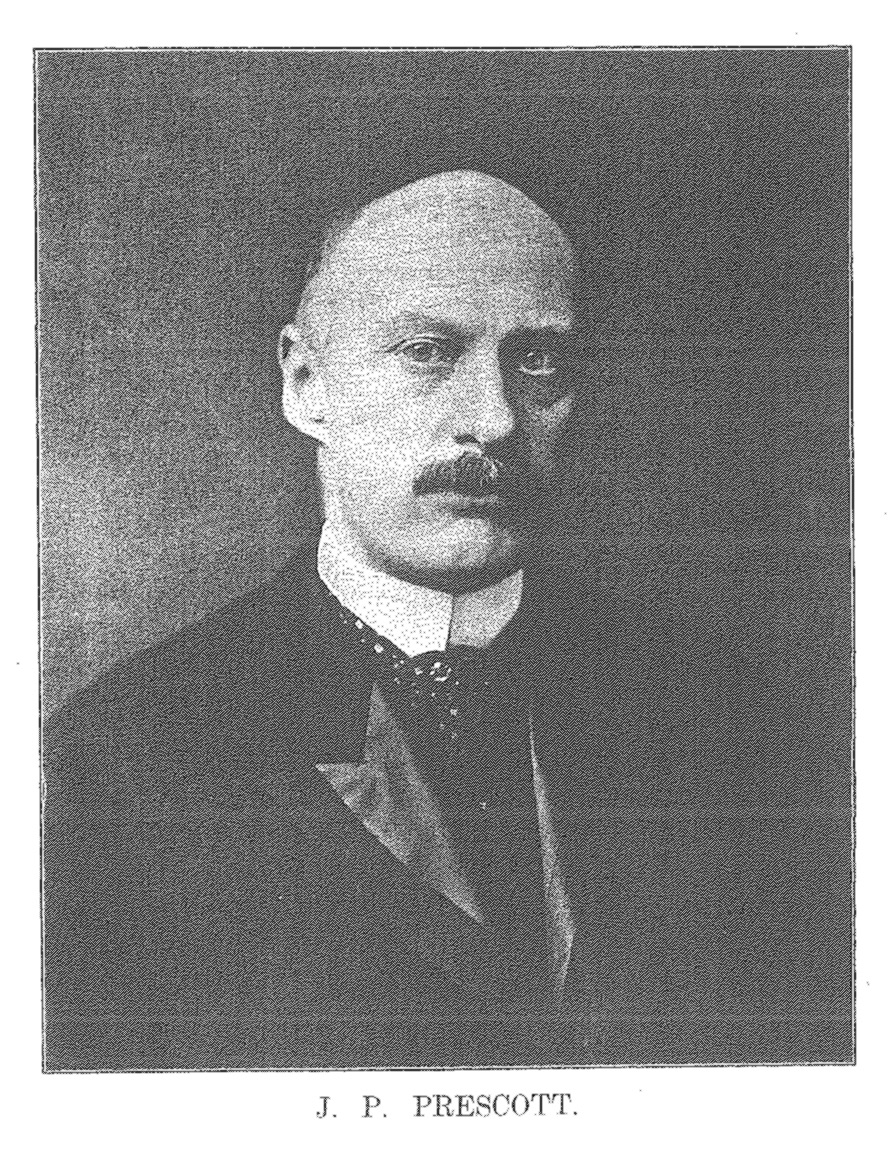

J.P. Prescott was a highly admired businessman, handsome in a very dignified way. When Carrie Westlake Whitney (the Kansas City Public Library’s first head librarian) published her three-volume History of Kansas City in 1908, she included a short biography and picture of Prescott as one of the city’s leaders. He was born in Iowa, and descended from Massachusetts Puritan heritage. Revolutionary War Colonel Prescott who was famous for his part at Breed’s Hill and historian William Hickling Prescott were lateral ancestors. He had first established himself in Kansas City ten years before, running a thriving milling business until he built the Terminal Warehouse in 1905, serving as the company’s president. He was a member of the Manufacturers & Merchants Association, the Commercial Club and the Kansas City Club, as well as being president of the Employers Association, having a “deep interest in the business outlook and prospect of the city.”

The year 1908 was far more important to Prescott for another, more personal reason.

On December 16th, Prescott was in the warehouse at Broadway and 25th Street on the third floor. He had pulled the rope to bring the elevator car down from the fifth floor, and tried to jump onto the platform as it came past the floor. His foot slipped and he got “caught between the beams of the lift and the shaft.”

Foreman J.F. Van Hatten was on a lower floor when he heard Prescott’s cry for help. Van Hatten ran to the elevator shaft just as the car passed. He jumped and landed on the platform, and then stopped the elevator.

The accident had crushed Prescott’s right leg and damaged both his arms. The doctors at Southside Hospital were afraid that all three would have to be amputated.

By the next afternoon, Prescott was improved. The doctors had been able to save his right arm, but had amputated both his leg and his left arm. He had rested well during the night, and was expected to recover.

Prescott had at least half a year of convalescence ahead of him. During that time he started searching, trying to find some sort of artificial arm that was more than simply decorative.

It was during this time that Prescott and William T. Carnes met for the first time.

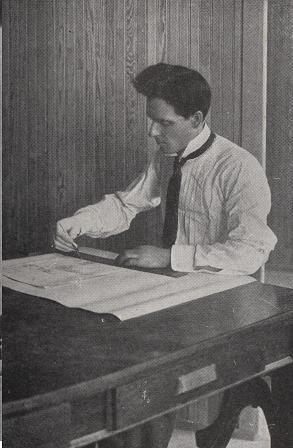

Carnes using his artificial arm

Carnes lived in Warren, Pennsylvania. His photos show a man with matinee idol good looks. He was a machinist, and in 1902 worked in a shop in Pittsburgh, running a large boring and milling machine. In the evening of February 13th, a rapidly spinning cog-wheel caught his right arm, and tore into it so badly that the doctor had to amputate it two inches above the elbow. Like J.P. Prescott some six years later, Carnes began looking for an artificial arm that would enable him to continue working. He checked several factories that made artificial arms to see what was available. He found out one unassailable fact—“that artificial arms were more ornamental than useful, and very little of either.”

Carnes bought one of these artificial arms, and wore it briefly. Wearing the arm convinced him to make one himself. He began a close study of the workings and movement of the human arm and hand, exploring the anatomy and experimenting with how to transfer the movements and abilities of a living arm to the gears, levers, and cranks of an artificial arm, one that would respond to the promptings of the muscles still in the remains of the living arm.

Carnes turned himself into an extraordinary engineer, developing amazing mechanical skill, and patiently, test by test, replacement by replacement, refining first one movement, then moving on to the next, he began the task of creating a working replacement for the arm he had lost.

Creating the prototype was an arduous and lengthy journey, in no small part because he was doing all the work with one arm and one hand. Once he had that working prototype completed, though, he was able to use it to accelerate the building of the next one. Carnes became very adept at using his new creation—which turned out to be a plus in the advertising.

After Prescott’s accident and the start of his search for a working artificial arm, he heard of Carnes. At some point he had gone to California to complete the regaining of his strength. That next spring he filled out his order for an arm and sent it to Carnes in Warren. In November he went to Pennsylvania to have the arm fitted.

I infer that Carnes probably did most, if not all, of the work on each arm ordered by himself. When Prescott arrived in Warren, he found that the arms were completed very slowly. Those who needed them simply had to wait.

Advertisement for the Carnes Artificial Limb Co.

This seems to have appalled him. According to the catalog later put out by the company the two of them would form, Prescott told Carnes, “You really haven’t a moral right to keep people waiting months for your arms.” Carnes told him he didn’t have the money to hire skilled workers to do the intricate work of making the artificial arms.

Prescott must have been very impressed with the arm Carnes had made for him, because he told the self-taught engineer that if Carnes were willing to move to Kansas City, Prescott would organize the capital and get a company going to produce the Carnes Artificial Arm.

Two years after they started the business in Kansas City, the Carnes Artificial Arm was being worn in 32 states and in Canada, and the Carnes Artificial Arm Company had grown so much that it had opened branch offices in Chicago, New York City, Pittsburgh, and Los Angeles.

The Carnes Artificial Arm had a

full-finger-motion hand and automatic turning and bending wrist and bending elbow, operated entirely by the use of the shoulder and stump to which the artificial arm is attached, without any assistance from the sound hand, the wrist being turned in unison with bending elbow or locked securely in any position desired by the wearer...

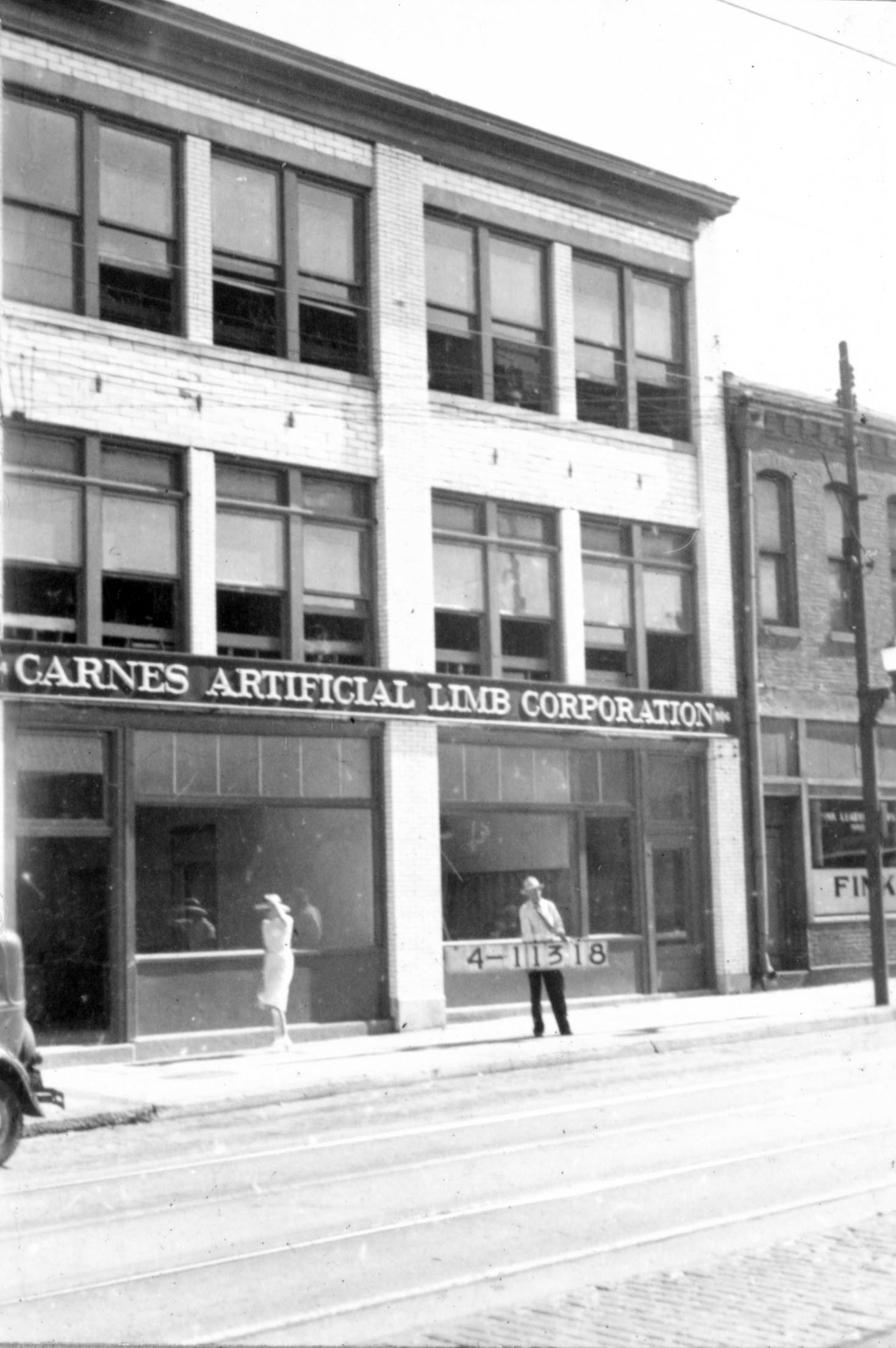

The Carnes Artificial Limb Co. in Kansas City

If you google “Carnes Artificial Arm” you’ll find references in old issues of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), as well as pictures of ads that appeared in Popular Mechanics and other publications from early in the 20th century. You’ll also find a hit for an article in the August 3, 1915, edition of the Kansas Citian magazine here in the Missouri Valley Room. It is titled “Highest Honors to Kansas City,” and tells how the Carnes Artificial Limb Company had received a “First Gold Medal” from the exhibition sponsored by the Committee of the Queen Mary’s Convalescent Auxiliary Hospitals in London, as well as having been awarded “highest honors, gold medal” from the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

This gets us to why this November history blog tells the story of the Carnes Artificial Arm.

World War I continues to grow ever distant in our memories. My grandfather fought in the war. After what his body went through during the war, his health was never strong again. Seven years from now will mark the centennial of its end. Though we have a great deal of literature about that war, works both creative and historical, for some of us the distance has overlaid a sense of quaintness to it. Faced with what the world faces today, it’s easy to dismiss and to forget the shock and trauma that World War I brought with it, to forget that it was the single most bloody and destructive war that the world had seen.

That’s why, as I have gotten to know about them, William T. Carnes and John Paul Prescott have become heroes to me. They and their work made an amazing difference to the post-war lives of an untold number of soldiers, sailors, and marines from several countries whose lives were much better than they might have been because, of Carnes’ genius as an engineer and Prescott’s as a businessman.

As we recently celebrated Veteran's Day, or Armistice Day as they called it at the end of the Great War, I thought you should know this story of two men who may not have served in the military during that war, but still served.

There is more to tell about them, but this will do for now.

[I want to thank Mark Lesek for his help in all this, especially for introducing me to the Carnes story. I think it was about a year and a half ago that I received an email from Mark, wanting to know if the Missouri Valley Room had any information about Carnes. I found the article in the Kansas Citian, as well as an article about Carnes’ later invention, a forerunner of the jukebox, and we exchanged a few more emails. Mark lives in Tasmania, the Australian island state that lies off the southeastern tip of Australia. Mark lost his arm in a car accident, and after learning about William Carnes, began researching the Carnes arm. He shared a great number of scans of photographs and other materials that aided immensely in my research. Mark has made major advances in his work to retro-engineer Carnes’ invention. We finally met this summer when he was in Kansas City and he came to the Missouri Valley Room. While in the United States, Mark also went to Montana, where he met Carnes’ descendants.]