Alexander Majors, was born to a farming family on October 4, 1814 near the town of Franklin, Kentucky. He eventually became one of the most important freight-haulers on the Santa Fe Trail, bringing him considerable fame and fortune in the 1850s. Today, however, Alexander Majors is most often remembered as one of the founders of the Pony Express.

Majors spent most of his childhood at the edge of the frontier in Missouri. At the age of 20, he married and settled on a farm in Independence, Missouri, where he would become a full-time trader in the late-1840s. In 1848, he set out with ox-drawn wagons on the Santa Fe Trail. The trail had extended from northwestern Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico since 1825 and had fueled the growth of the settlements at its eastern edge; especially Independence, Westport, and the Town of Kansas (now Kansas City, Mo).

On Majors' first Santa Fe excursion, he made the 1,600-mile round-trip in just 92 days, a record-breaking feat. He built on his newfound reputation, and by the mid-1850s he was guiding trade expeditions made up of more than a hundred of wagons and men, and more than a thousand mules.

In 1854, a minor change in government policy brought Majors into a partnership that would later result in the creation of the Pony Express. Military contracts for overland freight to the Southwest had become increasingly larger and more lucrative after the 1846-1848 Mexican-American War. In place of the existing patchwork of small freighters, the federal government sought one large company that would sign a two-year contract for overland freight.

Seeking a monopoly over western trade, Alexander Majors merged his company with former competitors William Bradford Waddell and William H. Russell. Together they won the two-year contract, and Russell, Majors & Waddell became the largest and most profitable freighting company that had ever been organized in the West. It employed more than 1,000 men, operated 5,000 wagons, and maintained a stock of 40,000 oxen. According to the Wornall Majors House Museums, the business relied considerably upon enslaved labor, and the partners supported pro-slavery political movements in Kansas. Majors personally owned at least six slaves, and they successfully escaped in 1860. Majors sided with the Union during the Civil War.

As quickly as Russell, Majors & Waddell arose, it ran into financial difficulties. Heavy losses of freight, workers, and livestock resulted in the late-1850s from severe weather, raids from Native Americans, and the 1857-1858 armed conflict between U.S. soldiers and Mormon settlers in Utah. The massive profits quickly evaporated, leaving the company in debt.

William Russell sought to alleviate this grim outlook by winning a contract to deliver United States mail to the west coast. Waddell and Majors were hesitant to support a venture that required such lofty overhead costs as 500 horses, but they eventually went along with it. When the Pony Express opened in April 1860, horse riders carried light loads of mail at rapid speeds to stations along the route. The riders would change horses at these stations and continue on their journey.

Because no railroads or telegraphs yet connected the East with the West, the Pony Express was the fastest way for the government or private citizens to send mail to settlers in California or anywhere along a route that roughly followed today's U.S. Highway 36, from St. Joseph, Missouri through Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada to San Francisco, California. Many detractors had argued that such a system could not be used during the harsh winter months, but in practice the Pony Express proved that it was a practical mail service year-round.

Financially, on the other hand, the Pony Express was a complete disaster. It failed to win the government contract that Russell had counted on, leaving the entire enterprise undercapitalized. The final blow came on October 18, 1861, when the Pacific Telegraph Company opened the first transcontinental telegraph line. Riders on the Pony Express delivered mail sporadically for a few weeks, but horseback riders simply couldn't compete with the speed of the telegraph. The Pony Express consequently closed after just 18 months in operation.

Ironically, Majors, Waddell, and Russell are rarely remembered today except as the founders of the Pony Express—perhaps their single greatest failure. Majors estimated the total losses to be roughly $300,000. Outside of those three individuals, though, hardly anyone remembered the Pony Express as a failure. Thanks to sensationalizing fiction writers, former riders, and sideshow performers such as William "Buffalo Bill" Cody, the image of lone riders struggling against the elements to deliver the mail on the Pony Express became a highly-romanticized Western legend.

Alexander Majors, one of Kansas City's most prominent early businessmen, could not fully share in the making of this legend. He lost his entire fortune when Russell, Majors & Waddell folded due to competition from the transcontinental railroads. He lived out the rest of his life on modest royalties from his autobiography and died in 1900 with relatively little money or renown.

This article was revised on July 15, 2020.

Read full biographical sketches of Alexander Majors, prepared for the Missouri Valley Special Collections, the Kansas City Public Library:

- Biography of Alexander Majors (1814-1900), founder of the Pony Express, by Daniel Coleman.

Visit the Pony Express National Museum at 914 Penn St., Saint Joseph, Missouri; (800) 530-5930.

Check out the Pony Express National Historic Trail, operated by the U.S. National Park Service, call (801) 741-1012 ext. 119 to request a brochure.

View images relating to the Pony Express that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Alexander Majors Residence; with accompanying historic article.

- Alexander Majors Portrait.

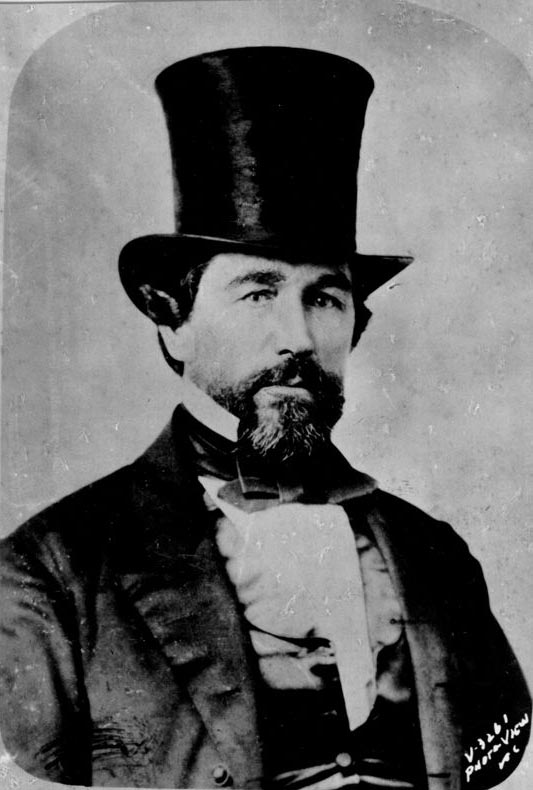

- Alexander Majors in top hat.

- Alexander Majors Residence, side view.

- Alexander Majors Residence, front view.

- Birthplace of the Pony Express, St. Joseph, MO.

- Pony Express Route; general color map with illustrations.

- Trails of the Old West; 1942 color map with illustration.

- Pony Express Trail; 1935 map.

- Painting of Pony Express Rider.

- Painting of Pony Express Rider; changing horses.

- Painting of Pony Express Rider; by men working on telegraph pole.

- "Pony Express Leaving St. Joseph, 1861;" artwork by W. Herbert Dunton.

- Bank of the State of Missouri; purportedly a resting place of Pony Express riders.

- Major George G. Asbury, helped reenact the Pony Express, 1912.

- Pony Express Station at Fort Bridger, 1923.

Check out the following books, articles, and films about Alexander Majors and the Pony Express, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- Seventy Years on the Frontier: Alexander Majors' Memoirs of a Lifetime on the Border, by Alexander Majors; Majors admitted that the publishers embellished many of the details in this autobiography for dramatic effect.

- Pony Express - The Great Gamble, by Roy S. Bloss.

- Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express, by Christopher Corbett.

- "From Hoofbeats to Fiber Optics: The Pony Express Launched Communications Legacy," by Anne W. Schultz, in Missouri Magazine, Fall 1994.

- "Many Lack Knowledge of 'Forgotten Communities,'" by Bill Gregg in History News, Winter 2009, published by the Wyandotte County Historical Society & Museum; describes forgotten communities, including a Pony Express stopover at 74th Street and Riverview Avenue.

- "Perserverence and Preservation: The Alexander Majors Home," by Jennifer Keith Mixson, in the Historic Kansas City Foundation Gazette, May-June 1984; describes the restored house of Alexander Majors.

- "Pony Express Just One Stop in Major's Life," by David W. Jackson in the Kansas City Star, February 27, 2008.

- "What Became of the Daring Young Men of the Pony Express?," by Myra Vanderpool Gormley, in Crossroads, December 2006; discusses the difficulties in uncovering the names of the Pony Express riders; also includes a list of 188 possible riders and a map.

- "The Oregon Trail; The Pony Express," Kaw Valley Films & Video, 1985.

- "The Young Riders," DVD, Stephen Baldwin; fictional television series set in the Pony Express.

Search the Kansas City Public Library catalog for dozens of other books and videos about the Pony Express, especially including many children's books.

Continue researching Alexander Majors and the Pony Express using archival material held by the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Vertical File: Pony Express.

- Vertical File: Museums--Pony Express.

- Vertical File: Western Union; replaced the Pony Express.

- Microfilm: Native Sons Scrapbook, Roll 30: Alexander Majors.

- Oregon Trail Memorial Association, 1960.

- "Overland Mail Carriers," by David A. White, in News of the Plains and Rockies, 1803-1865.

- Vertical File: Museums--Patee House; the museum was located at the old Pony Express headquarters.

- Pioneer Park Committee Records Finding Aid; the park contains a statue in honor of Alexander Majors.

- "Pony Express," by Michael S. Durham, in Desert between the Mountains: Mormons, Miners, Padres, Mountain Men, and the Opening of the Great Basin, 1772-1869, June 19, 1905.

- "Three Partners Sacrificed Fortunes and Names to Found Pony Express," in the Kansas City Times, April 3, 1940.

- Microfilm: Native Sons Scrapbooks, Roll 64: Pony Express and Various Stagecoach Lines.

References:

Louise Barry, The Beginning of the West: Annals of the Kansas Gateway to the American West, 1540-1854 (Topeka, KS: Kansas State Historical Society, 1972), 771, 808, 968, 1011, 1178, 1200, 1206.

Roy S. Bloss, Pony Express - The Great Gamble (Berkeley, California: Howell-North, 1959), 80-85, 96-97, 136-139.

Daniel Coleman, Biography of Alexander Majors (1814-1900), founder of the Pony Express, Missouri Valley Special Collections, the Kansas City Public Library.

Christopher Corbett, Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express (New York: Broadway Books, 2003), 5-9, 17-19, 22-23, 27, 50.

Henry C. Haskell, Jr. & Richard B. Fowler, City of the Future: A Narrative History of Kansas City, 1850-1950 (Kansas City, MO: Frank Glenn Publishing, 1950), 34.

Rick Montgomery & Shirl Kasper, Kansas City: An American Story (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 1999), 29, 39.

Raymond W. Settle, Mary Lund Settle, Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1955), 6-10, 29-51.