A grand opening ceremony on March 2, 1930 commemorated the new General Hospital No. 2, which soon became known as one of the nation's finest public hospitals serving African Americans. The new hospital unveiled intense divisions over racial segregation and machine politics, but it did manage to fulfill a longstanding demand for medical services and medical career training for the black community.

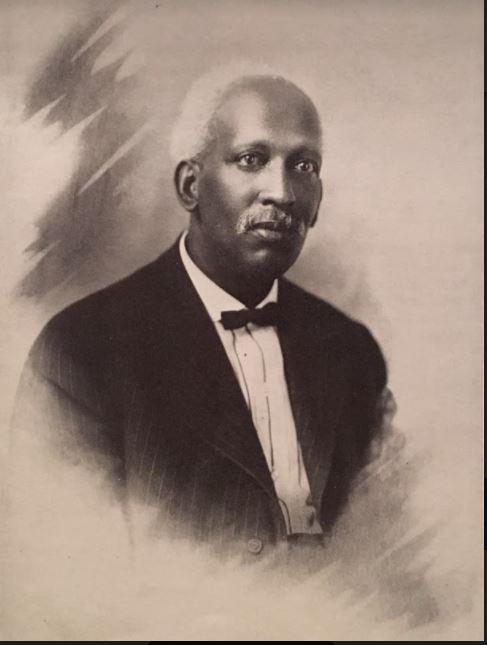

The story of General Hospital No. 2 dates back to the efforts of Thomas C. Unthank, a prominent black physician living in Kansas City at the turn of the 20th century. Unthank was born in 1866 in Greensboro, North Carolina. He graduated from Howard University School of Medicine in 1898 and then moved to Kansas City. Recognizing a need for more medical facilities for black patients, Unthank organized other black doctors in the area to found the Douglass Hospital in Kansas City, Kansas, in 1898, and the John Lange Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1902. Chronically underfunded, these private facilities failed to meet the demands of the black population, which accounted for nearly 10 percent of the population of Kansas City, Missouri. Public facilities were even worse, as black patients who sought care at the Old City Hospital faced segregation and, frequently, outright neglect.

Unthank believed that only a new public hospital catering specifically to minority patients could meet the demand. The 1903 flood, which destroyed much of the West Bottoms, confirmed the lack of facilities. The city only undertook a serious effort to treat area blacks and Hispanics affected by the flood after white patients were cared for, and then only at temporary emergency facilities at Convention Hall, not a proper hospital by any means.

As African Americans nationwide debated the potential costs and benefits of accepting racially segregated facilities, Unthank argued that a segregated facility would at least provide care for minority patients and even an unusual opportunity for the training of future black doctors and nurses. Thanks in large part to his lobbying efforts, the city designated the Old City Hospital to cater only to minority patients in 1908, after the construction of a brand new building for white patients, named General Hospital No. 1. Over time, the Old City Hospital came to be known as General Hospital No. 2.

From 1908 to 1911, General Hospital No. 2 had an all-white staff, but this situation began to change in 1911, when four black physicians, including Unthank, joined the hospital. By 1914, General Hospital No. 2 was the first public hospital in the United States operated entirely by African Americans. By the end of the 1920s, the hospital employed 292 persons, including 72 doctors, dentists, and nurses, and 57 student nurses. Despite the fact that the building was nearly 50 years old, undersized, and ill-maintained, the facilities were at least functional.

More dysfunctional were the local politics that surrounded the hospital. In the 1920s, the hospital's top administrative jobs became a reward for cronies associated with the political machine of "Boss" Tom Pendergast. Furthermore, a neglect of maintenance and updates created great fire hazards. These threats materialized in 1927, when a fire spread through the hospital, causing $30,000 of damage and threatening the lives of 60 patients. In response to the fire, the Municipal Commission approved plans for a new $300,000 hospital to replace General Hospital No. 2. The cause gained a boost from the Pendergast machine, which hoped to secure more votes from the African American community.

The final obstacle to the new General Hospital No. 2 building was an intense debate over the location. The original plans were to build it on Michigan Avenue near 26th and 27th Streets, near the southern edge of the black residential area of town. The Linwood Improvement Association, which represented the white neighborhoods south of 27th Street, protested because of fear that blacks would be encouraged by the hospital to try to move into the all-white neighborhoods. The city conceded and chose a site on 22nd Street, further north.

When General Hospital No. 2 opened on March 2, 1930, some observers considered it to be one of the finest hospitals in the nation, black or white. It was over seven stories tall and boasted all-new equipment. Chester Franklin, founder and owner of The Kansas City Call newspaper, happily noted that, "They did not try to build something 'good enough for Negroes' but something as good as money could buy." Occasional political interference with hospital operations continued, but it was an unusually nice facility for African Americans to have access to in the 1930s. It was also a culmination of the efforts of successful black professionals, like Thomas Unthank, who persevered against racism to secure proper medical facilities for minorities. The new hospital operated independently until 1957, when General Hospital No. 1 merged with General Hospital No. 2.

Read a full biographical sketches of people involved with General Hospital No. 2, prepared for the Missouri Valley Special Collections, The Kansas City Public Library:

- Biography of Thomas C. Unthank (1866-1932), Physician, by Nancy J. Hulston; Unthank was instrumental in the establishment of Kansas City's original General Hospital No. 2 in 1908

- Biography of William J. Thompkins, M.D. (1884-1944), Physician and Hospital Administrator, by David Conrads; Thompkins was one of the founders of the original General Hospital No. 2 in 1908, and the first superintendent of General Hospital No. 2

- Biography of John F. Ramos, Jr. (1920-1970), Physician and School Board Member, by Susan Jezak Ford; Ramos served his internship and residency at General Hospital No. 2

- Biography of Albert Isaac Beach (1883-1939), Mayor of Kansas City (1924-1930), by Nancy J. Hulston; Beach was mayor when General Hospital was built in 1930

- General Hospital No. 1 Profile (1908-1992), by Janice Lee; General Hospital No. 1 replaced Kansas City's original public hospital, which then served as General Hospital No. 2

View images of General Hospital No. 2 that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- General Hospital No. 2; exterior view, 1950

- Nurses Residence Area in General Hospital No. 2, 1950

- New kitchen in General Hospital No. 2., 1941

- Nutrition/Food Service in General Hospital No. 2; pictured with six employees, 1941

- Nutrition/Food Services in General Hospital No. 2, 1946

- Operating Room Facilities at General Hospital No. 2, 1945-1950

- Care givers shown with child; probably at General Hospital No. 2, 1950

Check out the following books and articles about General Hospital No. 2, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- Making a Place for Ourselves: The Black Hospital Movement, 1920-1945, by Vanessa Northington Gamble; discusses the movement in Kansas City, pp. 7-10, 53, 58, 165.

- "Kansas City General Hospital No. 2," by Samuel Rodgers, in The Journal of the National Medical Association, September 1, 1962, pp. 525-544, 639.

- Take Up the Black Man's Burden: Kansas City's African American Communities, 1865-1939, by Charles E. Coulter, pp. 209-216.

- From Shamans to Specialists: A History of Medicine and Health Care in Jackson County, Missouri, by Barbara Gorman, Richard D. McKinzie, and Theodore A. Wilson.

- "Kansas City General Hospital No. 2," by Joanne Chiles Eakin, in The Kansas City Genealogist, Summer 1997, pp. 15-16.

- "Surgeon Was a Pioneer," in the Kansas City Star, January 1, 2007; obituary for Walter Richard Peterson, Sr., a black physician who interned at General Hospital No. 2 and a founder of the Doctors Clinic at 25th Street and Brooklyn Avenue.

Continue researching General Hospital No. 2 using archival materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Kansas City Health Care Photograph Collection Finding Aid

- Kansas City Regional Oral History Project Finding Aid; contains some references to General Hospital No. 2

- Ramos-Lincoln Collection-Vertical Files: Health-Kansas City, Box 2, Folder 1

- An Interview With Samuel U. Rodgers; an intern at General Hospital Number Two and founder of the Wayne Miner Health Clinic (later renamed the Samuel U. Rodgers Community Health Center)

References:

Charles E. Coulter, Take Up the Black Man's Burden: Kansas City's African American Communities, 1865-1939 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 212-213, Chester Franklin quoted, 50-52, 209-214, 294, Chester Franklin quoted, 213.

Samuel Rodgers, "Kansas City General Hospital No. 2," The Journal of the National Medical Association, September 1, 1962, 525-544, 639.