Today, Guinotte Avenue is a rather unassuming stretch of road running through Kansas City’s predominantly industrial East Bottoms. One hundred seventy years ago, however, the thoroughfare was the embodiment of one man’s dream to make Kansas City a global city and a center of Belgian immigrant culture in North America.

Its history intrigued a local reader who asked What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, for insight.

Joseph Guinotte, the namesake of Guinotte Avenue, was born in the French-speaking Belgian city of Liège in 1815. A well-respected engineer by the early 1840s, he was appointed by Belgium’s king, Leopold I, to oversee construction of a railroad from Mexico City to Veracruz — under a government agreement to send engineers to construct railways in Mexico with Belgian materials. Before departing, Guinotte proposed to his sweetheart, Aimée Brichaut, and left with her promise that she would join him once he had settled in North America.

Joseph Guinotte. THE KANSAS CITY STAR

Unfortunately, his work in Mexico was interrupted by the Mexican American War and he left without completing the railroad. Instead, around 1848, Guinotte moved to the fledgling community at the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers that would become Kansas City. At the time it was a predominantly French community. Within two years, he established a farm in the rich bottomlands known today as the East Bottoms.

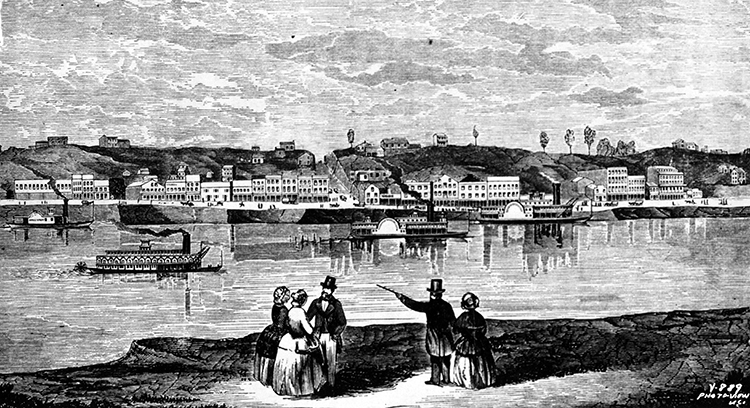

Guinotte quickly saw the potential of the riverside town. His friend, early Kansas City historian C.C. Spalding, wrote in 1858, “Mr. Guinotte has for years been sanguine that agricultural and mineral wealth, railroads, and river commerce would build a large city where Kansas is now being built.” Guinotte knew that to be a truly great city, it needed to attract new settlers, and he developed a plan to make Belgian immigrants the backbone of this future metropolis.

The Kansas City riverfront in 1855. KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY

In 1850, he formed Guinotte, Magis & Co. with two partners and approached the Belgian consulate in St. Louis with a rather ambitious plan. The company would pay for the transport, room, and board of 50 Belgian immigrants if they agreed to work for four years on land owned by the firm.

At the end of this term of service, the Belgians would be awarded 2.5 acres of land, as well as seeds, tools, food, and supplies to help them establish themselves as farmers. To house these immigrants, the company purchased 1,200 acres in the East Bottoms, mainly from the Chouteaus, one of Kansas City’s founding families.

On March 25, 1850, 50 men and women, along with 14 children, left Antwerp bound for St. Louis. These settlers had been hand-picked by the Belgian government for Guinotte’s project as they were deemed to be people of good character.

The trip was not without its problems. According to a complaint filed by a Mr. D’Ans, one of Guinotte’s indentured settlers, the journey was marred by bad weather, which led to the drowning of three of the ship’s nine crewmembers. Several Belgian settlers were forced by the captain to work as sailors despite their inexperience and inability to communicate in English. In addition, D’Ans maintained that the food and water were inadequate and often spoiled. The Belgian government dismissed the objections when they learned from other passengers that he was often drunk during the trans-Atlantic crossing.

The settlers arrived in Kansas City on June 22, 1850, thinking that the worst of their misfortunes were behind them. That was not the case. Within a month, two-thirds of the new arrivals were dead, apparently from an outbreak of cholera. Their bodies were interred in a mass grave somewhere in the East Bottoms. The few remaining Belgian settlers gradually abandoned the project, settling elsewhere in the region. Guinotte’s grand plans had failed.

Guinotte traveled in 1852 to New York, where he was reunited with his fiancée, Aimée Brichaut. The two were married by the archbishop of New York, with the Belgian consul as their witness, and quickly traveled to Kansas City.

Aimée Brichaut Guinotte. THE KANSAS CITY STAR

Aimée spoke no English, and, having been raised in a privileged Belgian family, was ill suited for the ruggedness of life in western Missouri. Local women, however, were immediately taken with her Parisian wardrobe, and many asked to borrow her dresses to make copies.

The Guinottes settled into a comfortable life of farming the rich bottomlands. Joseph built a large house overlooking the Missouri River and their farm, using logs cut from the well-forested bluffs. Later accounts record that the home, in the vicinity of Troost Avenue and Third Street, was one of the social centers of town, where everyone from neighbors to visiting dignitaries, and local American Indians would gather.

The Guinotte House in 1916. KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY

In 1855, the couple welcomed their first of four children, Jules Edgar. Lydia was born the following year, Emma in 1858, and finally Joseph Karl in 1860. In addition to the six Guinottes, the slave census of 1860 records that they held three people in bondage: a 21-year-old woman and two children, aged 7 and 5. This arrangement was typical for western Missouri at the time, and it is likely that the enslaved people, even the children, did everything from cooking and cleaning to farm labor.

With his hopes for a Belgian colony in Kansas City dashed, Guinotte began dividing his property in the East Bottoms into lots for industry, agriculture, and commerce. He designated one of the major thoroughfares as Railroad Avenue, correctly anticipating it would be the route of the future train lines.

He named another planned avenue after himself (Guinotte Avenue) and two additional streets after his eldest children, Edgar and Lydia. As the plots of land sold, brick yards, sawmills, quarries, and other commercial and industrial ventures began to take over.

The intersection of Lydia and Guinotte avenues. The tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad, seen in the rear of the image, follow Guinotte’s Railroad Avenue. PATRICK SALLAND

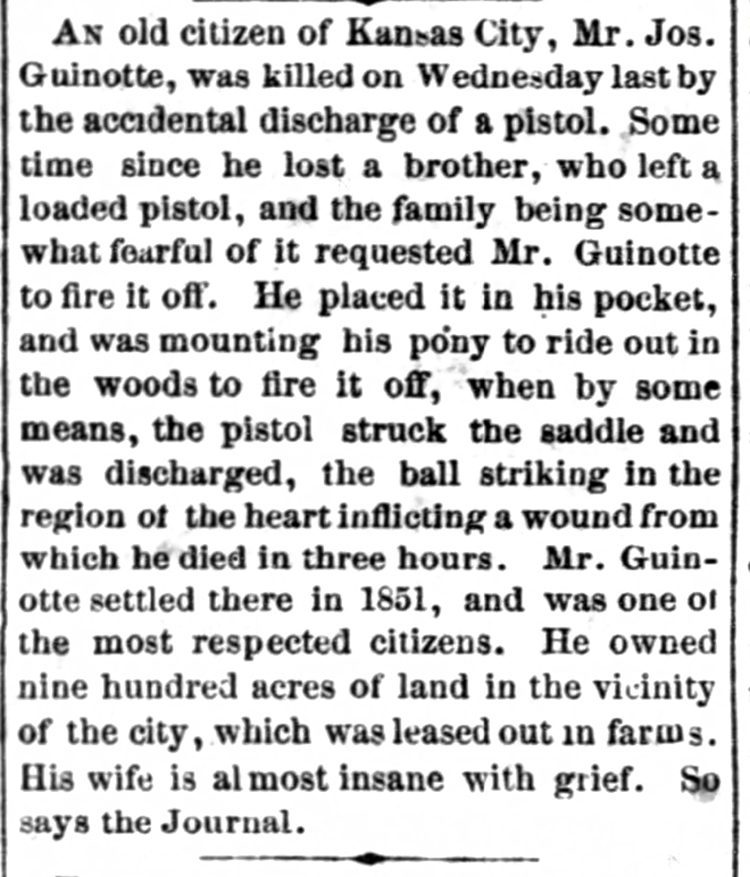

On September 5, 1867, Joseph Guinotte died under mysterious circumstances. Several newspapers, including the Daily Missouri Republican, reported the death as a suicide. Others shared a different account. The Daily Kansas Tribune reported that Guinotte’s deceased brother had left a loaded pistol in the home. “[Guinotte] placed it in his pocket and was mounting his pony to ride out in the woods to fire it off, when by some means, the pistol struck the saddle and was discharged … inflicting a wound from which he died in three hours.”

The Death of Joseph Guinotte as reported on September 7, 1867. THE DAILY KANSAS TRIBUNE

In 1907, about 18 years after the family moved away, the log house Joseph Guinotte had built became a subject of debate. City leaders had decided to raze the dilapidated dwelling and build a playground. Many citizens spoke out publicly in favor of preserving the structure, which they argued was the final remnant of Kansas City’s early history.

Guinotte Manor, a Kansas City Housing Authority apartment community, is located on the approximate site of Joseph Guinotte’s log house. PATRICK SALLAND

The house was ultimately demolished, and that same year, Aimée Guinotte died at age 84. Eldest son Jules Edgar became a probate judge for Jackson County, Joseph Karl a well-respected architect, and Lydia and Emma both educators. Joseph Guinotte’s success, built in no small part on the unpaid labor of the people he enslaved, was the springboard for the achievements of his children. Ultimately, despite the failure of his attempts to create a Belgian community in Kansas City, he left an enduring legacy through his development of Kansas City’s industries and rail infrastructure, helping to propel the city into the 20th century and beyond.

Judge Jules Edgar Guinotte from Political History of Jackson County, 1902. KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.