On a hill off Eastern Avenue, just south of where 1-435 now intersects Raytown Road, once stood a building with a complicated past. The two-story, concrete structure served as Kansas City’s tuberculosis hospital for almost 50 years until it was closed and abandoned in the summer of 1964. Vandals soon laid claim to the place, and it was demolished in 1971 to make way for a Kansas City Police Department helicopter unit.

Circa 1940 view of the Kansas City Tuberculosis Hospital.

John McNamara remembers his older siblings sneaking into the building to scare themselves before it was torn down, prompting him to ask, “Can you tell us more about the old tuberculosis hospital?” The What’s Your KCQ team, a community reference partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, has the details.

TB in KC

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that tuberculosis was responsible for one out of seven deaths in North America and Europe during the 1880s. And Kansas City was not immune.

Reliable infection data for the city is scarce before 1900, but death notices and advertisements for medicines and treatments indicate TB was indeed present. In 1901, health officials recorded a death rate of 188.8 per 100,000 residents from pulmonary TB (tuberculosis of the lungs). In 1905, approximately 13% of all reported deaths within the city limits were from the disease.

Doctors had limited understanding of the illness but treated patients as best they could. They knew it was bacterial and contagious. And since it often manifested itself in crowded, polluted, and poorer urban areas, they reasoned a change in environment and lifestyle would combat it. They prescribed much fresh air and sunlight as possible, total bed rest, and consumption of only the most nutritious foods (up to five meals a day). Isolating the infected and attention to personal hygiene were also essential.

In 1909, KC philanthropist William Volker funded a small, free clinic at 11th and Charlotte streets. The Volker Pavilion allowed doctors to move about a dozen TB patients out of regular hospitals, freeing up needed beds and decreasing the risk of infection for others. Tents and small wooden structures provided the sick with constant air circulation and easy access to the sun. The clinic offered walk-in services for patients who were still at home and made nurses available for house calls to those who needed extra care.

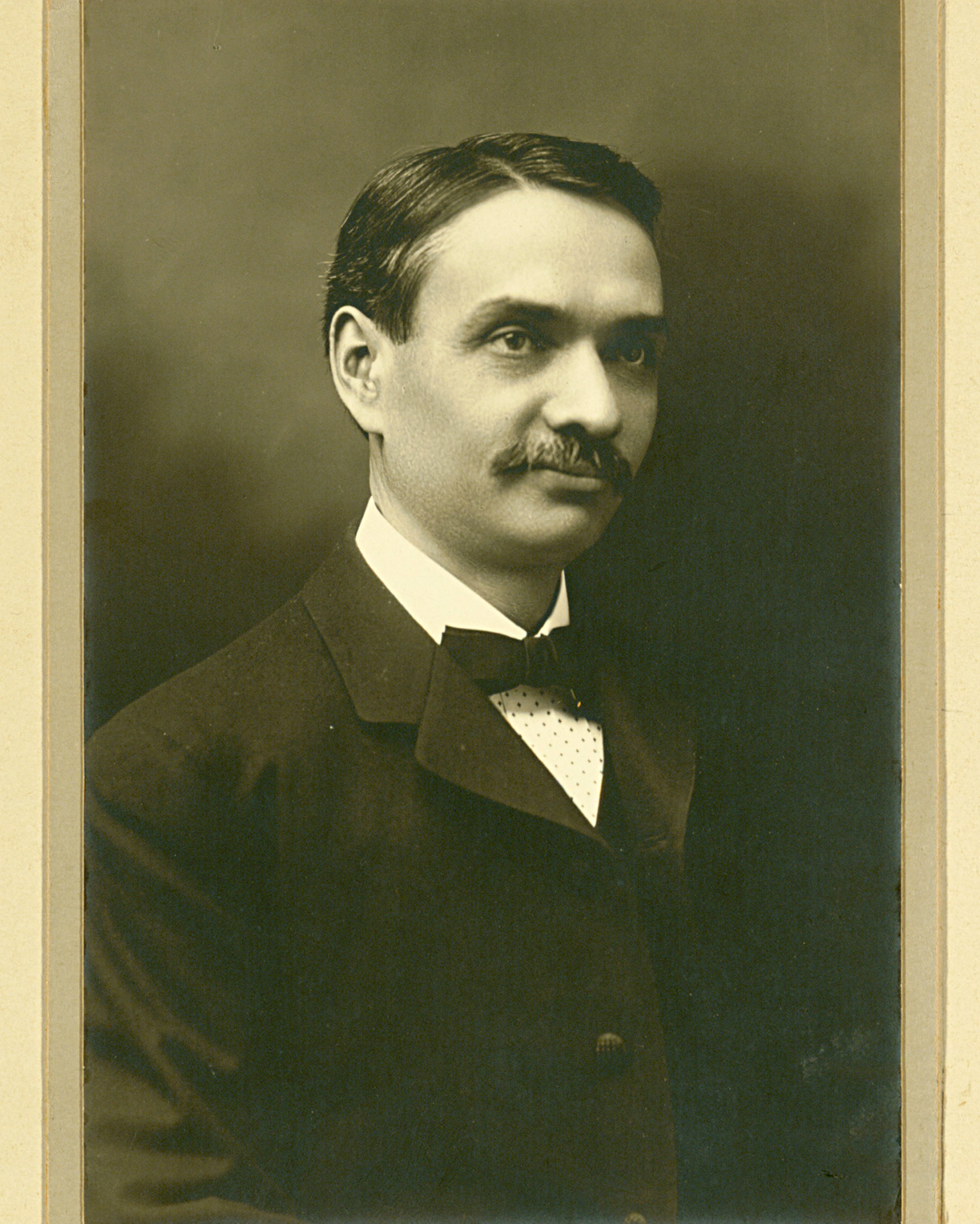

1917 portrait of William Volker.

But the pavilion was not large enough to meet demand. There was always a waiting list. And with the city continuing to grow, downtown air was not as fresh and clean as it was in the country.

In 1910, residents approved a bond issue for the construction of a dedicated tuberculosis hospital. The selected site was east of KC proper, on land already used for the Municipal Correctional Institution, also known as Municipal Farm.

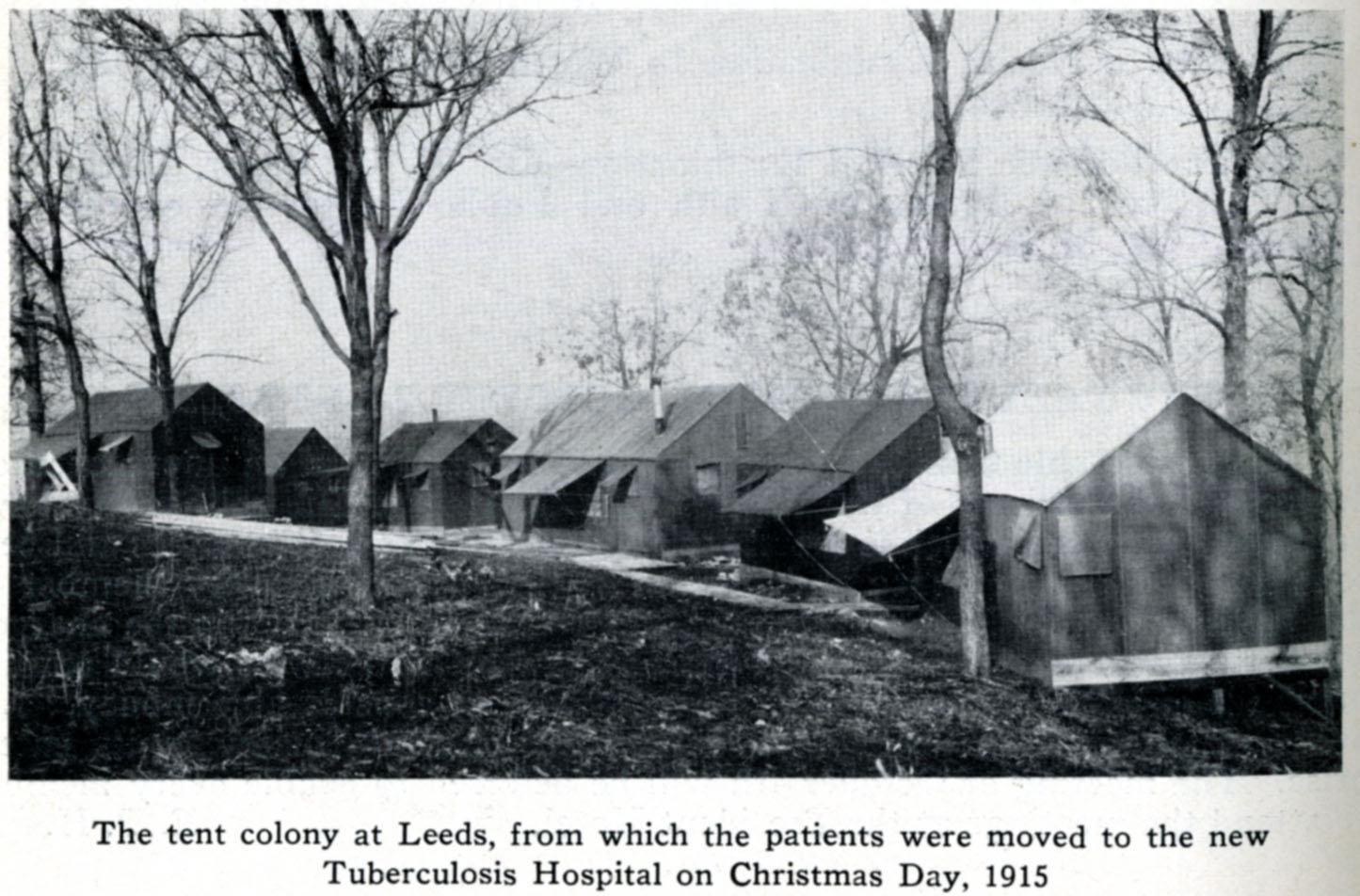

Administrative and funding issues prevented construction for several years. In the interim, the Health Board established a tent colony near the planned hospital site. Six large tents with wooden floors, beds, coal stoves, and running water housed a total of 15-20 patients and an onsite nurse. The director of the colony reported that it cost “a remarkably low sum of 70 (cents) per patient per day to maintain this camp.” Accessible only by streetcar, followed by a ride up a muddy and sometimes snow-covered hill, the colony often ran low on supplies. It was a relief when the new building was finally ready.

The Leeds Hospital

Construction on the hospital began in 1914 and finished in 1915. Inmates from Municipal Farm provided most of the labor and, with that, a significant cost savings.

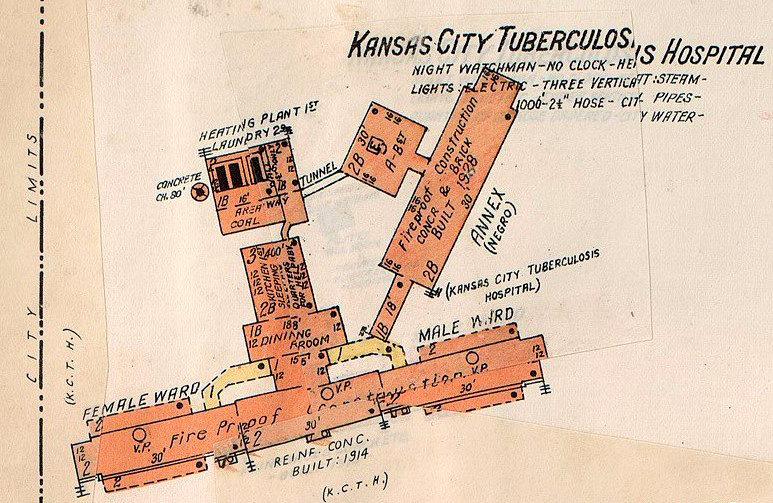

Architect E.P. Madorie spent months surveying tuberculosis sanitoriums across the country before settling on a design. The building featured two long sleeping wards with large windows that easily opened. The units were connected by a perpendicular wing that included the dining hall, kitchen, and utilities. Wide porches allowed patients to lie in the sun on reclining chairs.

1945 Sanborn fire insurance map displaying the Kansas City Tuberculosis Hospital.

The hospital opened December 25, 1915, to 18 patients who were then at the tent colony. But the building was still mostly unfurnished, and it took time before all the boxes and barrels were unpacked. The planned celebratory Christmas turkey dinner had to be delayed by two days.

Though the TB hospital was owned and operated by the Kansas City Board of Health, it was closer to the community of Leeds, which almost immediately earned it the name Leeds Hospital.

Money Shuffles

Financial issues plagued the hospital at the beginning. Big enough to house about 150 patients, it initially had only the equipment and resources for 40. Treatment there was free, so its operation was dependent on funding from the Board of Health, which was stretched thin.

Costs were cut wherever possible. The board went so far to contract prisoners from the nearby Municipal Farm to work as orderlies in the hospital; but the arrangement did not last. On December 9, 1917, The Star reported that the facility would close because it was too expensive to maintain. Patients were sent back to General Hospital.

But the TB hospital was not shut for long. In January 1918, an outbreak of smallpox forced health officials to reopen the building. It was easier to isolate smallpox patients out in Leeds than in any of the city hospitals.

By June that year, smallpox was on the decline and the hospital was again repurposed to alleviate crowding in General Hospital. According to The Star, this time it was to house “women detained for treatment of the social diseases.”

Under the city’s vice ordinance, women diagnosed with sexually transmitted diseases could be forcibly hospitalized (essentially jailed) under the guise of protecting public health and safety. A July 6, 1918, article in The Star described how 40 female patients had escaped from their locked ward, some prying open boarded up windows and using bedsheets tied into ropes. Thus, only cooperative female patients were to be sent to the Leeds Hospital. Uncooperative patients were to be sent to the Women’s Reformatory at 20th and Vine.

On August 7, 1918, tuberculosis returned to the hospital. About 20 female patients exchanged places with 34 TB patients from General Hospital. The Board of Health’s annual report notes the transfer but does not offer a reason, though it likely was tied to a rising patient count from the deadly 1918 influenza pandemic.

Segregated Health Care

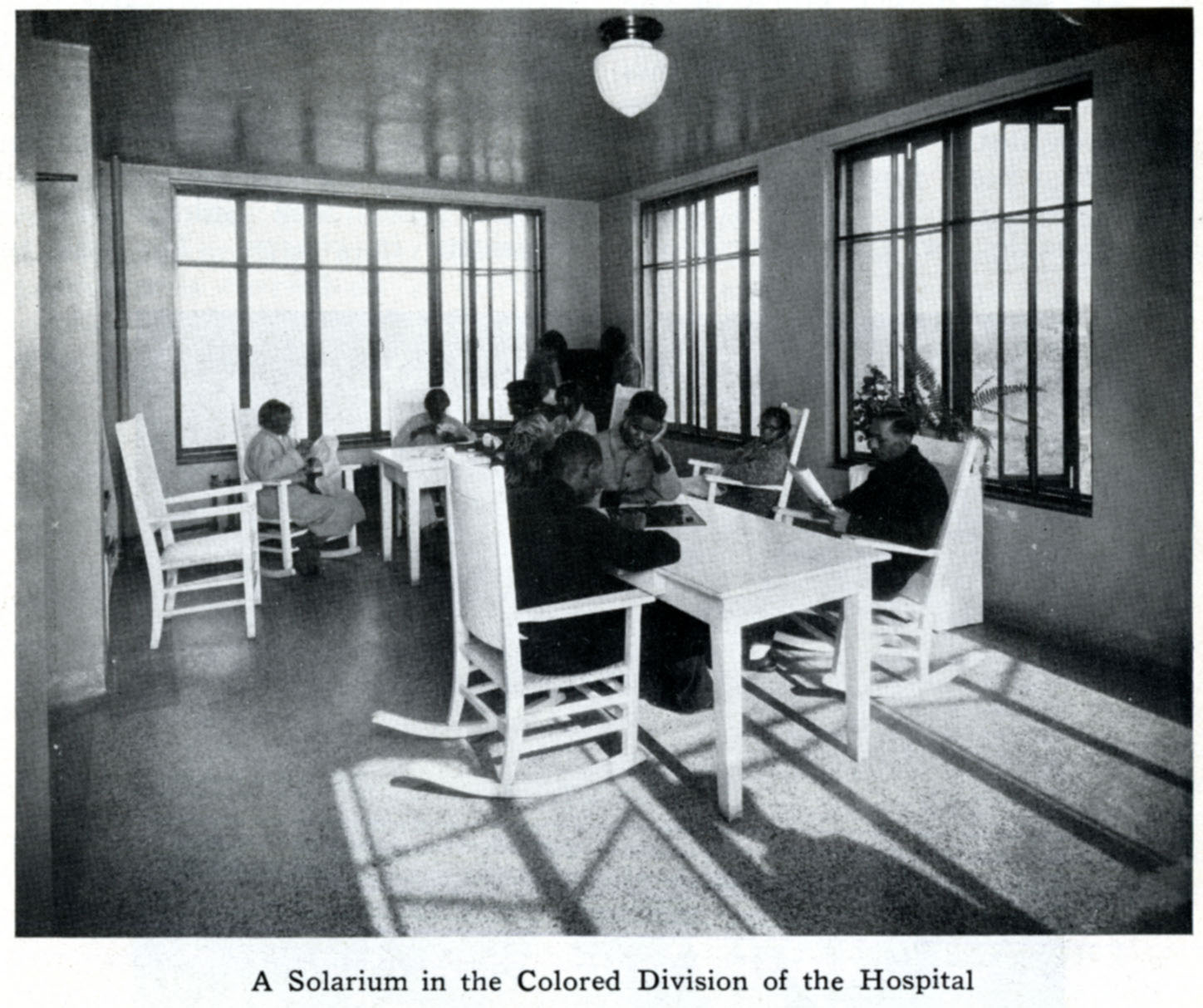

When it opened in 1915, Leeds Hospital was designated for white residents of Kansas City with TB. A clearing house, set up at the city’s all-white General Hospital, assigned patients with moderate symptoms to Leeds and those severely ill to an isolation ward in a city hospital. Milder cases could be treated at home. African Americans with tuberculosis purportedly went through similar sorting at the all-Black General Hospital No. 2.

White Kansas Citians may have been introduced to the inequalities of the city’s health system with a scathing letter from Dr. William J. Thompkins, former head of General Hospital No. 2, to Mayor Frank Cromwell. Printed in The Star on December 13, 1923, it detailed the dilapidation of General Hospital No. 2, as well as the “old wooden shacks… just above the terminal tracks” where TB patients were housed. Conditions in the shacks were so terrible that most doctors and interns refused to treat patients there, forcing nurses to “stay in ‘an atmosphere of death’ all the time.”

The letter was part of a larger campaign by a biracial committee advocating for new health care facilities for Black residents. Progress was slow, but the group eventually succeeded. A new General Hospital No. 2 was completed in 1930, a year after an annex was added to the TB hospital for Black patients.

Life in the Hospital

Published, first-hand accounts from hospital patients are hard to come by, if any still exist. But there are glimpses of what life was like there.

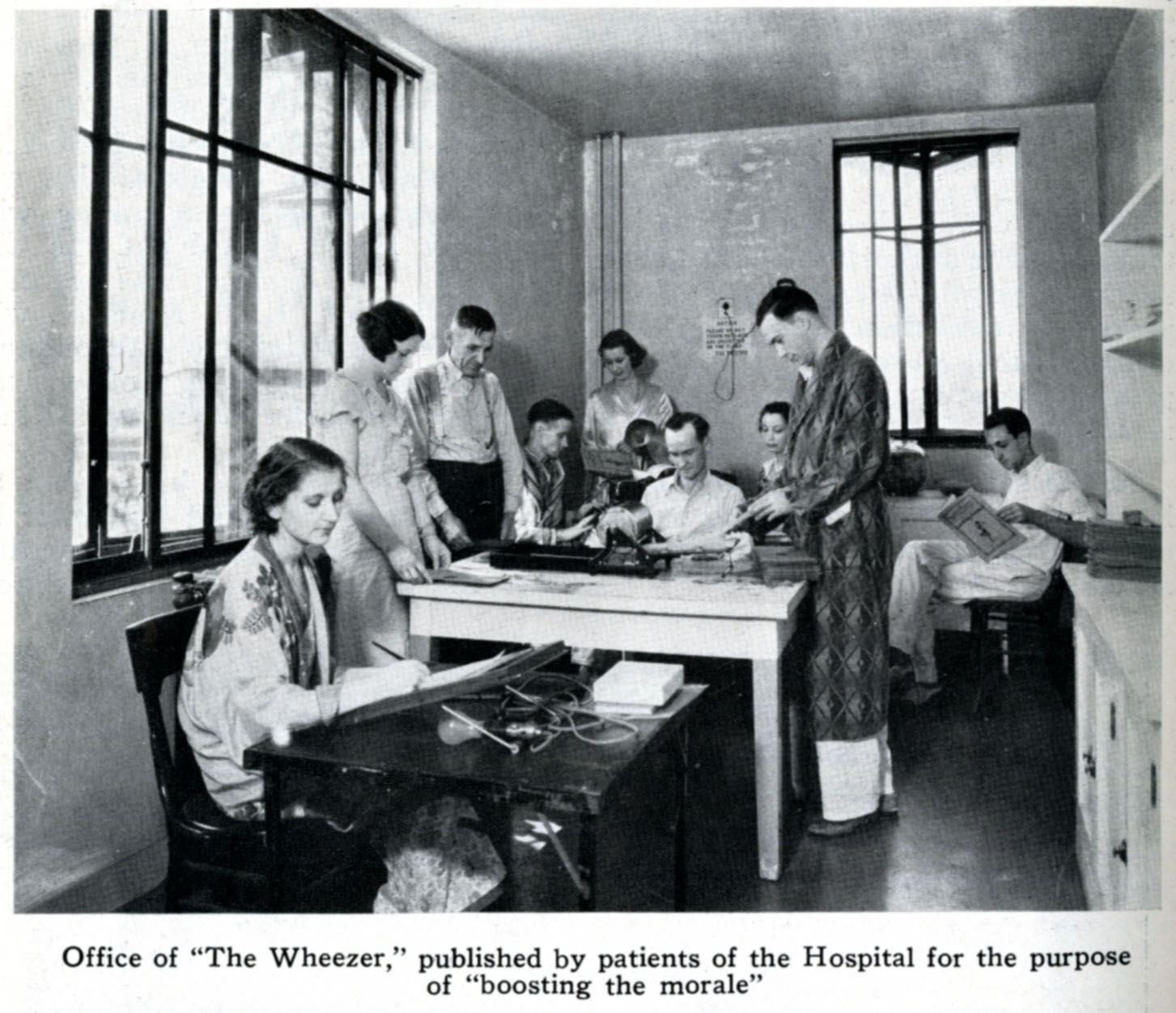

In her 1919 report to the Board of Health, the hospital’s head nurse lists various amenities the patients enjoyed, including bimonthly moving picture shows, music from a victrola and recitals, speaker presentations, prayer meetings, and numerous games of checkers, cards, and more. In 1934, The Star touted the availability of radio headsets, a library, outdoor games and gardens, and annual parties thrown by a former patient. The Jackson County Medical Journal made special note of the patient-run newsletter, “The Wheezer,” as a morale booster.

However patients passed the time, they were still sick and kept isolated from their families and homes. They were also subject to the daily management – or mismanagement – of the hospital.

Accusations of mistreatment, poor food, and deteriorating infrastructure periodically appeared in the newspapers. In 1919, the outgoing head of the hospital and Municipal Farm, Dr. Carl A. Nylund, publicly criticized the hospital for deplorable conditions.

As Nylund asserted to The Star, “due to incompetent nurses – and only too few of them, at that – lack of proper medicine and sanitation, the Tuberculosis Hospital is so conducted that it is impossible to effect a cure. When a person enters the institution as it now is conducted, he is on his way to the undertaker’s; there is no exception.”

The staff was inexperienced, unproductive, and punished patients who complained. And because of short-staffing, ambulatory patients helped care for those confined to their beds. The food was awful. The building was filthy.

Following an investigation by the city’s Welfare Department that confirmed the allegations, the Board of Health promised to swiftly address the problems. But it resisted overhauling the hospital’s management, insisting the supervising nurse’s work was “highly satisfactory.”

Management of the hospital may have been the greatest challenge to overcome. As with most city departments from the 1910s through the 1930s, the Board of Health was dominated by appointees with strong ties to the Pendergast Machine, and they in turn hired loyal supporters to staff city services. The TB hospital was no exception.

Politics again came into play in May 1926. The head nurse, Nelle Roberts, was suddenly fired and replaced by Nell Cronin, an outspoken advocate of powerful Democrat and Justice of the Peace Cas Welch, who controlled 36 precincts east of downtown.

Cronin had previously been in charge of the hospital, but patients reported she was harsh and ineffective. In contrast, patients and doctors loudly praised Roberts’ work and vehemently protested her removal. Health Director Dr. Ernest W. Cavaness was quoted in The Star as saying, “I admit this is political, but what is to be done?”

City Manager Henry McElroy stepped in, and Roberts was rehired the next day.

Hospital operations appeared to improve in the latter half of the 1920s and into the ‘30s. Stories of patient dissatisfaction occasionally made it into the newspapers but on a smaller scale and less frequent than before. Funding remained a constant issue, though.

Moving Out

Antibiotic treatments developed in the 1940s through the 1960s were major breakthroughs in the struggle against TB. But as medicine improved, the large hospital on the outskirts of town where patients were prescribed sun and rest grew outdated.

Meanwhile, a different kind of health crisis arose in Kansas City. In the 1950s, the municipal hospital system was suffering from severe overcrowding and aging infrastructure. The Health Department determined a complete reorganization was needed and began taking steps to consolidate and restructure.

Early in June 1964, TB patients were moved out of Leeds Hospital and into the old Research Hospital at 23rd and Holmes. Its proximity to General Hospital made it easier for patients to receive X-rays and special treatments. The Star described “the formidable moving operation” as “completed in a day.”

The building in Leeds was officially closed for the last time.

TB patients in their new lounge at the old Research Hospital from the July 1, 1964, edition of The Kansas City Star.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.