The American West, and in particular the Native American peoples that inhabited western lands, were a source of fascination for Euro-Americans in the nineteenth century. As the nation expanded westward guided by the doctrine of "manifest destiny," authors, artists, and photographers followed and documented the settlement of the western frontier.

The late-nineteenth century was a period of upheaval and cultural change for Native Americans tribes confined to sections of Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. Tribes were forced to merge with other tribes and adopt a Euro-American agricultural lifestyle. In 1889, the “Unassigned Lands” in the heart of Indian Territory were officially opened to white settlement. Towns such as Guthrie, Stillwater and Oklahoma City sprang up overnight as thousands of settlers or “boomers” staked their claim to choice lands in these newly opened regions.

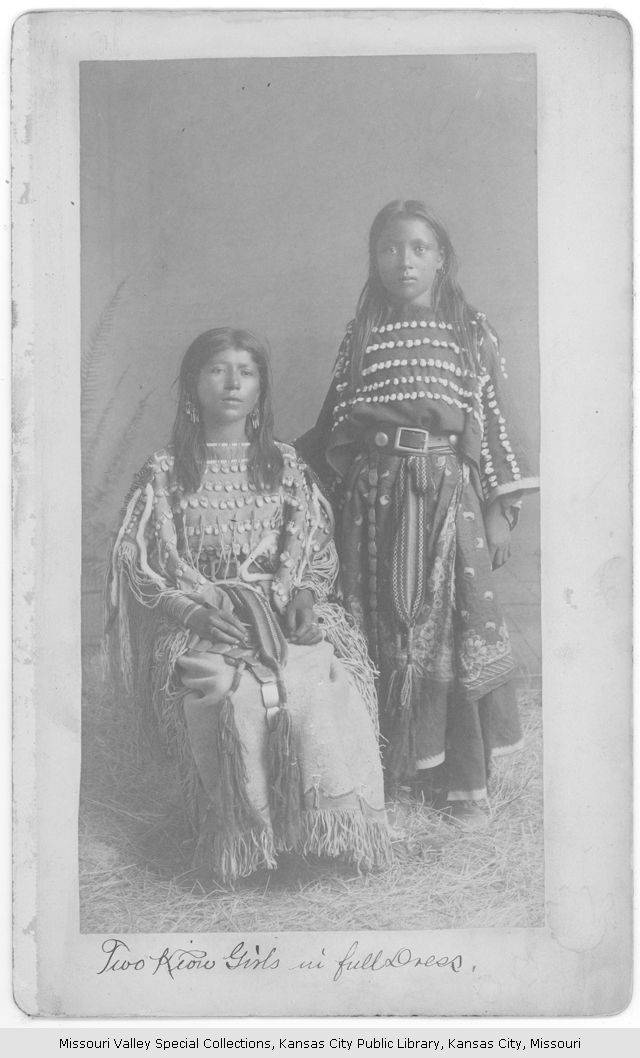

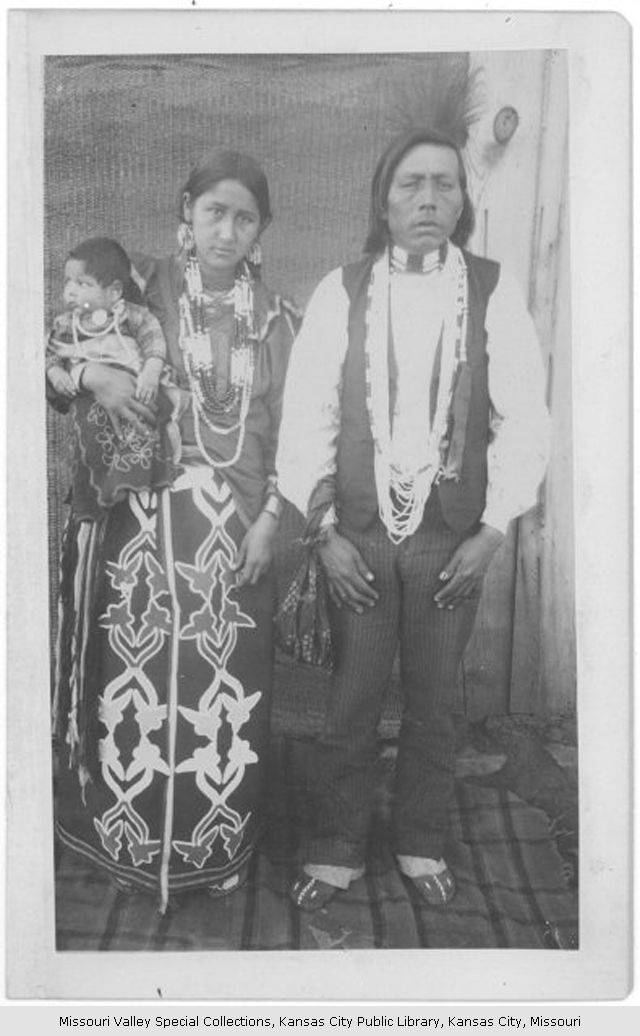

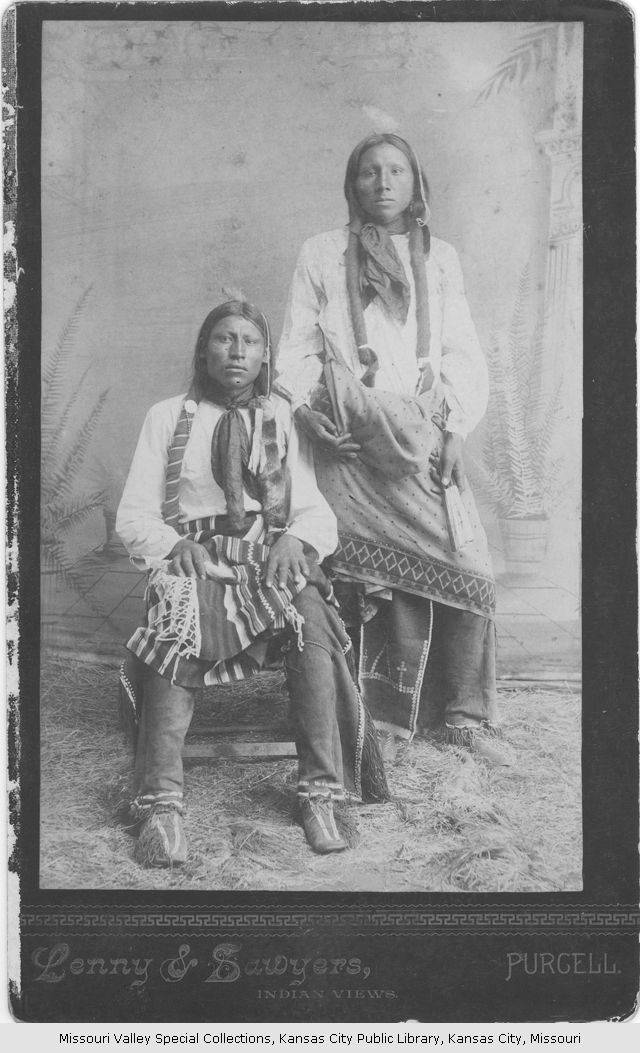

Professional and amateur photographers alike flocked to Oklahoma-Indian Territory where they set up studios and documented frontier life. These photographers ventured into surrounding Indian reservations and captured images of the Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Osage, Otoe, Ponca, Sac (Sauk) and Fox, Pawnee and other tribes. Photographic images of Native Americans were in demand by people in the eastern United States and throughout Europe who were fascinated by the rapidly vanishing customs and traditions of these indigenous cultures.

The motives of frontier photographers varied; while some considered themselves to be visual historians and strived to accurately record life in Indian Territory, numerous others capitalized on the plight of the Indian and perpetuated stereotypical images of the stoic “noble savage” held by Euro-Americans.

Prints of Native Americans were commonly mounted on cabinet cards, boudoir cards and stereographs, and sometimes included a title and name of the photographer. These conveniently formatted cards were marketed to western tourists, as well as eager buyers in eastern U.S. cities where they were displayed prominently on cabinets and bureaus.

While many of the images perpetuated stereotypes and did not accurately depict Native American life and customs, they do give us a glimpse into a period of displacement and acculturation for the Southern Plains Indian tribes in Oklahoma-Indian Territory as they struggled to adapt to a new lifestyle forced upon them by government policies and encroachment by white settlers. Furthermore, these images give us insight into the motives, techniques and work of the frontier photographer.

William S. Prettyman, Arkansas City, KS

In 1893, Prettyman settled in the newly formed town of Blackwell in Oklahoma Territory where he served for two terms as mayor. In 1905, he sold his photography studio in Blackwell and moved west to California. Prettyman’s former partner and protégé, George B. Cornish, is responsible for preserving many of his original plates and later published an album of Prettyman’s work titled Oklahoma Indian and Cowboy Views.

Thomas Croft, Arkansas City, KS

Thomas Croft was another prominent photographer in Arkansas City and an associate of William Prettyman and George Cornish. Like Prettyman, Croft made several trips into Indian Territory in the 1880s and captured images of reservation life.

Lenny and Sawyers Gallery, Purcell, Indian Territory

Lenny, a field photographer, was thought to have taken most of the photographs, while Sawyers managed the studio in Purcell. Many of their photos were reproduced in the 1890 U.S. Census.

The Native American/Western Photograph Collection is housed in the Special Collections Department of the Kansas City Public Library. The collection contains over 143 glass plate negatives, boudoir/cabinet cards and assorted prints of Native Americans from the late-1800s through the early-1900s. In addition, there are numerous scenes of boomer settlements in Oklahoma-Indian Territory and cowboy images. Digitization of the collection is ongoing.

Sources and Additional Readings:

- Cunningham, Robert E. Indian Territory: A Frontier Photographic Record by W.S. Prettyman. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1957. [976.65 P94I]

- “Documenting Native American Life” Exhibit. National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum Fleming, Paula Richardson and Judith Lynn Lusky. Grand Endeavors of American Indian Photography. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

- Johnson, Tim. Spirit Capture: Photographs from the National Museum of the American Indian. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998. [779.997 S759]

- Mautz, Carl. Biographies of Western Photographers: A Reference Guide to Photographers Working in the 19th Century American West. California: Carl Mautz Publishing, 1997. [MVSC Q770.922 M45b]

- Wright, Muriel H. A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951. [MVSC 970.3 W95g]

Article written by: Jeremy Drouin, Special Collections.